|

|

||

|

NASA often prepares its astronauts for the weightlessness of zero-gravity by immersing them in massive pools and water tanks, treating the slow, drunken movements of scuba diving as an experiential substitute for deep space. Hopeful astronauts, in full waterproof regalia, are thus plunged into a surrogate world, one that refers to the unique challenge of off-planet environments, whether that’s the International Space Station or the surface of the moon. The architecture associated with these two worlds – the astral and the oceanic – also shares many structural similarities. Submarines and space stations both depend upon the complex management of a highly compartmentalised interior space designed less for aesthetics than for pure function: rigorously divided by air locks and on constant guard against leaks, collisions and everyday wear and tear. On the other hand, these comparisons soon break down. Most obviously, the environmental pressures work in opposite directions in each setting: a structure in zero-G must protect itself against over-pressurisation and explosion into the vacuum that surrounds it, while a submarine needs to flex itself neverendingly against the crushing strength of the ocean. Nonetheless, the buildings, bases, rigs, ships and cities associated with human colonisation of the oceans often resemble the architecture of deep space exploration – and while 2001: A Space Odyssey and Star Wars have justifiably received their due architectural attention, the undersea imagination has yet to be equally rewarded.

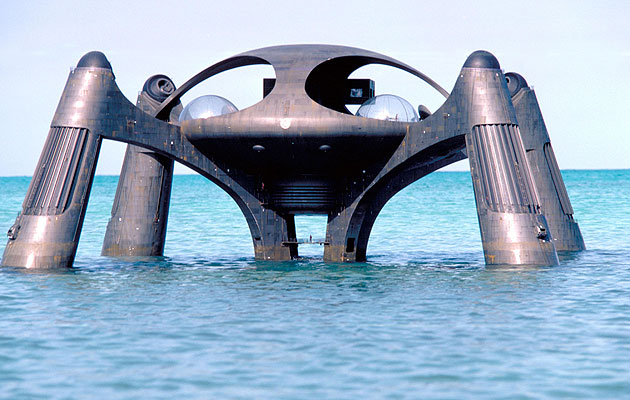

credit The Costeau Society As we’ll see in the examples gathered here, the prospect of humans moving en masse into the seven seas offers a surprisingly fecund field for architectural speculation. From the lyrics of pop songs with their yellow submarines to cat-and-mouse Cold War thrillers, and from Jules Verne’s explorer Captain Nemo to the conspiracists’ lost cities, the spatial challenge of taking a maritime plunge inspires near-endless architectural daydreams. A survey of some of the more memorable design cues taken from this world under the sea also yields a convenient, though under-explored, slice through architectural history – suggesting future environments for films and games, but also shedding light on how architecture can make the inhospitable inhabitable. The Abyss (1989, directed by James Cameron) The film presents us with a team of deep-water oil workers stationed on the seabed of the Gulf of Mexico. Their submersible drilling rig – with production design by Leslie Dilley – is both claustrophobic and hyper-pressurised against the unimaginable external weight of the ocean. The film’s sets achieved a level of Oscar-nominated authenticity by being physically constructed, not limited to green-screens or CGI. Exterior views of the rig and crew were shot inside the flooded containment building of an unfinished nuclear power plant in South Carolina. The resulting full-scale, undersea environments were thus buried in nearly 40ft of water. The Spy Who Loved Me (1977, directed by Lewis Gilbert) The intolerable excess of Stromberg’s dining room, however, is in direct contrast to the smooth, industrially designed command rooms and armouries located below water level. Down in the heart of Atlantis, we see a massive golden globe that maps the world’s oceans, the waters of our blue planet shining with the colour of treasure: a reversal of foreground and background in which it is the oceans that attract and inspire mad conquest, not the pathetic and empty lands that they erode and quietly swirl around. Sphere (1998, directed by Barry Levinson) In the astonishingly bad Michael Crichton adaptation Sphere, a special team of variously skilled scientific experts are sent to the bottom of the Pacific Ocean where a 300-year old spacecraft the size of a football pitch has been discovered, covered in coral. What they find, however, to their badly acted surprise, is a time-travelling spaceship apparently Made in the USA: the signs are in both English and Spanish, and there are steps perfectly scaled for the human body. But then, they find that perfect golden sphere … The sets remain noteworthy, even if the film does not, for continuing one of author Crichton’s signature tropes: the architectural environment frames a Zeno’s Paradox of alien encounter. In other words, with every room or level you enter, you move further and further into an increasingly anti-human environment, inching closer and closer into contact with something otherwise entirely outside of human experience. As in Crichton’s own film The Andromeda Strain (1971), it is a carefully regulated architectural sequence that makes this encounter possible. Stingray (1964-1965, created by Gerry and Sylvia Anderson, who also made Thunderbirds) Dolphin Embassy (1974, designed by Ant Farm) The resulting architectural form is triangular, powered by “fluidic” computers and roaring with the “suction rush of water” through a network of pipes and pontoons. The embassy would even include “dual human-dolphin controls”, on the off-chance that our cetacean cousins – when we’re not shagging them – might want to go for an oceanic joyride. Conshelf I, II and III (designed by Jacques-Yves Cousteau) Cousteau’s own underwater architectural experiments were less utopian than scientific, known as Continental Shelf (or Conshelf) I, II and III. These spatial prototypes would test the proposition that humans – “oceanauts” – could live beneath the waves, foraging for seafood every now and again while living in harmony with the global tides and currents. Formally speaking, Conshelf I was perhaps the most interesting. A domed tripod covered in coral, located 10m below the waves of the Red Sea, was connected to a submarine hangar and equipment store below; deeper yet was a station for a more extreme testing of physiological reactions to underwater life. Conshelf II can be seen in Cousteau’s 1964 documentary, Le Monde Sans Soleil (World Without Sun). The following year with Conshelf III, six “oceanauts” lived 100 metres below the sea for three weeks. Bioshock (2007, created by Irrational Games/Ken Levine)

credit Rex Features |

Image The Kobal Collection

Words Geoff Manaugh |

|

|

||