|

|

||

|

In the 1950s and 60s, as the steam slowly hissed out of rail, an unprecedented transformation in our roads, our lifestyles and our architecture was taking place. Why do we shun this era? Yes, this was the golden age of transport. It’s true that the post-war era has little that can compare with the splendour of the Victorian railways, or with Frank Pick’s gesamtkunstwerk in London. But, if we tear ourselves away from rail’s allure, a far more significant revolution – in architecture, in design and, most importantly, in opportunity – was taking place. Yet we persist in having a casual regard, even a scorn, for its importance, and its impact on both our environment and our lives. To dismiss entirely the achievement and importance of rail in the 1950s and 60s would be frivolous. That one-time powerhouse London Underground did complete the underfunded Victoria Line, given a futuristic veneer by Design Research Unit. And, in aesthetic terms, British Rail deserves its current spin on the nostalgia merry-go-round, centred around the masterly graphic identity of 1965, also by DRU. Criticised on launch as overly Germanic, its plain signage, pared-back typeface and low-key liveries were cost-effective, credible and conspicuous amid the fripperies of commerce. Its famed double arrow (‘a piece of twisted barbed wire’) has survived fashion and privatisation. Other projects deserve celebration: after the powerful Deltics, British Rail produced that perennial favourite of trainspotters, Kenneth Grange’s InterCity 125, generating four decades of rhapsody. But these projects were lipstick on a huge, ailing pig. After holding their own in the early 1950s – a billion passengers a year, a decent share of freight, even a (very) small profit – Britain’s war-weary railways hit the buffers, trapped by decaying infrastructure, tight regulation of services and fares, pay disputes, a reliance on steam and, in 1955, a first operating loss. The Modernisation Plan that year was an illusion, throwing £1.2 billion at the chimera of long-term profitability, much of it wasted on the short-haul freight market as it vanished to road. |

Words John Jervis

Above: Abbotsinch Airport, Glasgow (1966) by Spence, Glover & Ferguson |

|

|

||

|

Coventry Station (1962) by London Midland Region (project architect: Derrick Shorten) |

||

|

Valuable experiments in prefabrication, system building and even space frames did take place, and a group of ambitious modernist stations resulted. Particularly celebrated at the time was the work of the Eastern Region – Broxbourne’s ‘slab over the rails’ with its forceful service towers, to which Harlow added layered roofs and robust finishes. Ian Nairn even described the cantilevered Barking, modelled on Rome’s Stazione Termini, as ‘one of the noblest new buildings in London’. Less fashionable was Chichester and Banbury’s Festival of Britain-lite, although it has stood the test of time well. Yet passenger and freight usage declined and losses escalated. Funding proved intermittent and the notorious, necessary ‘Beeching Axe’ was round the corner. There was just one undisputed success: the hard-won electrification of the West Coast Mainline. Its Inter-City service, launched in 1966, cut journey times between London and Manchester by an hour, doubling passenger numbers. Numerous stations with aspirations to grandeur ensued. Stafford and Coventry boasted clean, tall concourses and jutting canopies. Cost-cutting hit Manchester’s Piccadilly hard, but Max Clendinning’s nearby Oxford Road was a prefabricated Sydney Opera House in laminated wood, topped by conoid shell roofs. Even the reviled Birmingham New Street had its signal box (see p.21), ‘a tour de force of plastically wrought concrete’, effused Jonathan Meades. Nairn’s verdict? ‘All wavy concrete panels and likely to look absurd within ten years.’ Sadly, British Rail’s underlying economic and political disarray was epitomised by Euston, the grand terminus of the newly electrified line. The station was to have been topped by seven silo-like towers, a shopping mall, cinema, bowling alley and restaurants, designed by a Taylor Woodrow team under Theo Crosby, leading the incipient Archigram. British Rail’s finances and the contentious Brown Ban on office development in London sabotaged all but the platforms, freight area and signal box.

The central pier and lighting gantry at Gatwick Airport (1958) by Yorke, Rosenberg and Mardall London Midland Region’s team took over, producing the low-lying structure seen today: a simple, colonnaded form clad in black granite and white mosaic, its spacious airport-style interior bathed in light from clerestory windows. A dour parcel office straddled the tracks: only with the erection of Richard Seifert’s blocks in the 1970s was Euston’s commercial potential partially realised. The station’s restrained modernism won praise (even the Victorian Society admitted its ‘formal dignity’); most in the industry felt it was a modern, efficient advance on its predecessor. John Betjeman, however, criticised it as ‘a disastrous and inhumane structure’; the Smithsons blustered, falsely, that the Euston Arch had never needed to move. In truth, rail was never going to forge a new Britain – the unprecedented transformation in architecture, economy and lifestyle was taking place elsewhere. Air passengers jumped 30-fold between 1950 and 1965. And, although airport design was in its infancy, YRM’s Gatwick was hugely influential, even attractive. The first European pier airport, its lightweight grid of steel beams and silkscreened glass infills created external and internal coherence while allowing for expansion upwards and outwards. Integrated into road and rail, Gatwick’s success led to commissions at Luton, Stansted and the classy Newcastle, a product of the firm’s white-tile era. Basil Spence’s Glasgow, with its cantilevered ‘umbrella of concrete vaults’, also cut an impressive figure but, with landscaped gardens by Sylvia Crowe, was more town hall than transport hub. But it was the private car that radically remodelled mass transport, and the entire country, in the 1950s and 60s. It shaped not just suburbs, as railways had done, but entire towns, from Birmingham and Glasgow to Harlow and Milton Keynes. UK car licences rose from 2.2 million in 1950 to 13 million in 1975 – major design spin-offs included Kinneir and Calvert’s Transport typeface and motorway signage, Alec Issigonis’s Mini, David Mellor’s traffic lights and Grange’s parking meters.

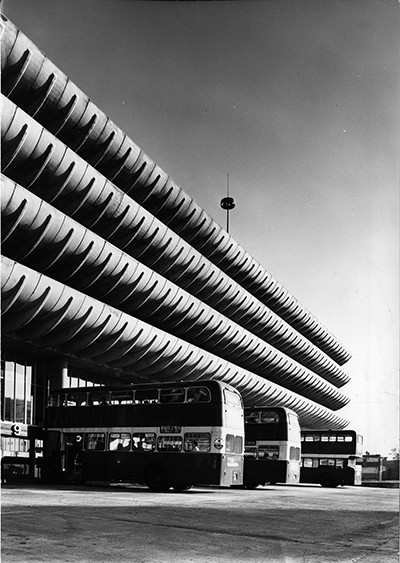

Preston Central Bus Station (1969) by Building Design Partnership The primacy of the car was seen as both inexorable and desirable – the white heat made available to all. Even bus traffic declined in its wake: celebrated depots and stations such as Newbury Park, Stockwell and, to a lesser extent, Bournemouth were pre-war hangovers, their soaring concrete roofs a makeshift response to steel shortages. As ambition declined, bus stations became subsidiary to and subsidised by offices, shopping malls and civic centres. And, of course, the car. The magnificent Preston is essentially a massive 1,169-space car park with a failed bus station below – Europe’s largest – its 80 gates serving a ‘Lancashire New Town’ that never arrived. The open-deck, multi-storey car park was the boldest urban expression of the new lifestyle. Often integrated into offices, market halls and shopping centres – most ostentatiously at Owen Luder’s Tricorn Centre in Portsmouth (‘the first no-holds barred explosion’ of a new architecture, pronounced Nairn) and Trinity Square, Gateshead (with its empty rooftop nightclub) – these were other-worldly arrivals, utterly unlike their surroundings. Intimidating facades and claustrophobic interiors; repetitive, abstract elevations of slabs against dark voids; and exposed, utilitarian materials were all offset by spiral ramps of fluid concrete. These were the castles of the new city, complete with turrets for pedestrian access. Unreliable mechanical car parks such as the City of London’s Zidpark – celebrated by Peter Cook in Archigram 4 – were speedily demolished and, despite such feats as Bloomsbury Square’s double helix, undersquare parks proved too expensive. Far more successful were staggered-floor and, more spectacularly, helical- and continuous-ramp examples. The first of the latter was the two-way cantilevered spiral at Rupert Street, Bristol – a city that proved a particularly zealous devotee of the car park, from the tight spiral ramp of Tollgate to the double-diamond frame at the Unicorn Hotel. Such facades served to lessen scale, provide interest and hide staggers, reaching a zenith with Michael Blampied’s sculptural load-bearing V-blocks at London’s Welbeck Street.

Welbeck Street Car Park (1968–70) by Michael Blampied and Partners Beyond the city, it was the arrival of the trunk road that changed everything. In the mid-1950s, Britain – with industrial production falling behind Germany and France, huge military budgets and growing balance-of-payments deficits – belatedly threw its lot behind the guaranteed returns of the motorway over rail’s quagmire. The network grew with immense speed to 1,600 miles in 15 years (though with shamefully slow progress outside England), throwing up innumerable flyovers, tunnels, earthworks and bridges, which moulded entire landscapes in their virile wake. The first 53 miles of the M1 alone required 130 of Owen Williams’s reinforced-concrete bridges (one completed every three days), abused as ‘the ugliest set of standardised structures in Britain’ by Reyner Banham. Later extensions produced sleeker prestressed examples, and such engineering showpieces as the five-spanned Trent River Crossing. And, on the heels of the graceful, aerofoil-decked Severn Road Bridge, came Philip Larkin’s ‘swallow-fall and rise of one plain line’: the Humber Bridge. Construction began in 1971 on the longest suspension bridge in the world, serving an illusory north-eastern industrial dawn. The 559 concrete columns over rail, river and canal at Birmingham’s Spaghetti Junction also elicited appropriate awe. Nairn was a dedicated fan of the genre, calling the M4 extension: ‘A leviathan rearing out of the mediocrity of the Hounslow bypass … the blunt concrete T-pieces have brought back a scale without brutishness that has been missing since the Victorian viaducts.’ The cumulative effect of these great constructions propelled Britain towards a new modernity, revolutionising work and leisure habits, the nature of housing and holidays, manufacturing models and the logistics of freight. And, above all, mindsets. The popularity and impact of motorways were unassailable, despite the scenery, archaeology and communities laid waste in their creation.

Gravelly Hill Interchange (‘Spaghetti Junction’) (1968–72) by Owen Williams They were considerably more expensive, destructive, intrusive and controversial when imported into cities: ‘gashes through millennial history’ as Banham put it. After initial post-war hyperbole around Swedish and American ‘urban motorways’, the ambiguous 1962 Buchanan report heralded a decade of turbulence. Despite disquiet, major road schemes continued across the country: in Leicester and Nottingham (competing to become the major city of the East Midlands); in Leeds and Liverpool; and, suspiciously late (and with integrated car park), in T Dan Smith’s ‘New Brasilia’, Newcastle. London was left with the destructive, elegant Hammersmith Flyover, as well as stunted remnants of its ‘Motorway Box’, from Europe’s longest elevated road, the Westway (‘the embodiment of all the science fictions I had ever read’, recalled Will Self) to the new Blackwall Tunnel, ventilated by Terry Farrell’s Niemeyer-inspired shafts. Similarly, the Mancunian Way, with its 18 subways, was abandoned in 1967 with a slip road hanging in mid-air. This petrol explosion – facilitated by the advent of super-tankers, deep-sea drilling and new refinement technologies – also transformed filling stations and garages, and created an entirely new typology: the service station. As filling stations multiplied to an all-time peak of 40,000 in 1967, pre-war vernacular and moderne stylings were abandoned. Instead, they evolved from simple modular structures in the 1950s – the first modernist buildings in many towns and villages – via Markham Moor’s hyperbolic paraboloid, to Eliot Noyes’s overlapping circular canopies for Mobil. Garages were less experimental, but service stations were encouraged by officialdom to adopt futuristic (if stubbornly unprofitable) forms that gave views of the new concrete expanses: Farthing Corner’s open bridge with sun umbrellas for dining or the Terence Conran-styled ‘restaurant on a bridge’ at the sleek Leicester Forest East. This flamboyance reached a peak with the 22m-high airport-control-tower restaurant and sun deck at Forton, Lancashire, before ebbing away into practical mundanity. Yet we care so little about all these structures, which enhanced lives, shaped our present, and often achieved genuine beauty. Rail has at least benefitted from a certain rigour in listing and its habitual out-of-town locations. Euston’s demolition has, however, been assured by last year’s crass refurbishment. A new mezzanine inside and tasteless matt cladding outside preclude any further listing attempt; the site is now being hawked as a ‘development opportunity’ by Deloitte and Network Rail.

Forton Motorway Service Area (1964–65) by TP Bennett & Sons Commercial imperatives have given modernist airports little chance. The redevelopment of YRM’s Gatwick and Frederick Gibberd’s immense Heathrow has been constant, and, in the early 1990s, Spence’s Glasgow was concealed behind cheap white panelling. The architecture of the roads is equally vulnerable – the boom in property values has made what were once considered peripheral urban areas enormously valuable. Bus stations, now seen as unnecessarily bulky, are casually torn down, from Northampton’s factory-like Greyfriars to Slough’s more ecclesiastical Brunel. Car parks are even more exposed, their demise hastened by environmental concerns and advances in automobile technology. Iconic structures such as Luder’s Trinity Square and Tricorn Centre have gone, Welbeck is next on the list. Other typologies are considered ephemeral. Only one of Noyes’s Mobil stations remains; Markham Moor is shuttered and rotting. A host of related structures is under threat – the curvilinear showrooms, the car factories with their monitor roofs, even the truncated pedways. Perhaps the distribution centres, business parks and out-of-town malls will be next. A cloying sentimentality around Eagle cutaways of mechanical marvels – Comets, Concordes, Advanced Passenger Trains, Blue Streaks and any number of abortive British helicopters – should not disguise their premature demise. We need to put aside this national obsession with noble failure and instead celebrate what has really mattered. The first drive-on drive-off ferry terminal at Dover revolutionised lives; the Hovercraft did not. While time and money are thrown at dead-ends, the prosaic yet transformative is being destroyed. This was a golden age: for a brief moment it seemed that Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin, or even Archigram’s Plug‑In City, might be realised. Real life soon kicked in, but it had been altered forever. This article first appeared Icon 169 – read more about the issue here |

||