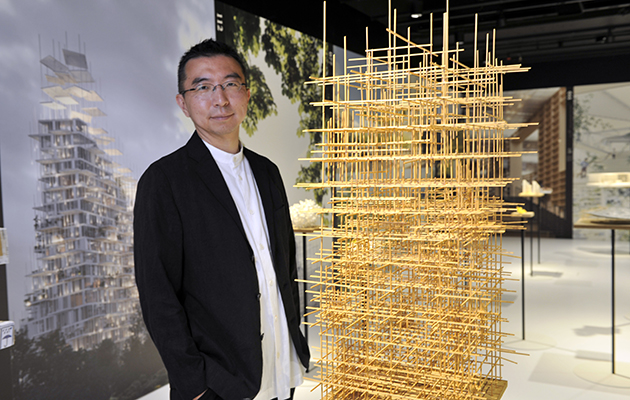

Sou Fujimoto, acclaimed Japanese architect, in his exhibition Futures of the Future at Japan House London

Sou Fujimoto, acclaimed Japanese architect, in his exhibition Futures of the Future at Japan House London

As Japan House opens its doors in London, Rita Lobo spoke to Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto, whose exhibition Futures of the Future is inaugurating the new space.

The third outpost of Japan House, after LA and São Paulo, has opened in London with an exhibition by cult architect Sou Fujimoto.

Located in a serviceable Art Deco building in Kensington High Street, the new space aims to present the best of Japanese culture, art, and shopping to the world. Inside there is an exhibition space, gallery, theatre, as well as a specialist travel agency, a design-led shop, and a top sushi restaurant.

Fujimoto’s Futures of the Future exhibition is the natural choice to open the space. He is well known to UK audiences because of his successful Serpentine Pavilion, and the show ties in the London Architecture Festival, but above all the exhibition brings the thought-provoking work of one of Japan’s most challenging architects into a space that is as much about Japanese architecure as it is about culture.

Icon sat down with Fujimoto at the opening of Japan House London for a catch up:

ICON: Futures of the Future is about space, shape and volume, but it’s an art exhibition. How do you navigate being an architect and artist, and how do you bring those two together now?

Sou Fujimoto: Well for me, I’m always even making such a tiny artistic things. My thinking is based on the architecture thinking, the starting point is how we can create the place for people, for a better life, or for different types of communications, and different types of the relationship of the privacy and the public and so on. All the ideas are coming from that kind of basic thinking relating to the people’s life, so in that sense it is quite architectural.

One of the tiny models at Sou Fujimoto’s Futures of the Future

One of the tiny models at Sou Fujimoto’s Futures of the Future

But of course, many ideas, sometimes crazy ideas, look like art pieces. For example, the pieces in the exhibition are almost like Marcel Duchamp works or something. I was really inspired by that, so for me every time the starting point is architecture, a place for people, and then of course I’m open for people to think this looks more like an artistic or something.

Icon: What’s your process like? How important is this sort of making and drawing and working with your hands?

Sou Fujimoto: The starting point of course we do the basic researches about the programs, former examples, and history of the areas, and climate, all this kind of basic research is a very basic starting point. And then I start to discuss with my team a craziness of the ideas and we make some sketches or sometimes we make some such a tiny sketch models. All of this is just to see a lot of different potential. We like to have unexpected ideas from our normal thinking, so that first phase is really expanding our brains and expanding our ideas. And through that process, those kinds of tiny models, we try to test or try to transform normal things into architecture, then that process always opens our minds to create new perceptions of architecture spaces. But of course, at the same time we are using the computer to check the volumes.

In that sense, our processes, trying everything, not only physical models, not only computers, not only sketches, sometimes just a discussion by words or conversation is also quite important. So using all of those kinds of methods or media just to see the wide range of the craziness of the ideas.

ICON: You’ve spoken before about this natural imagery being central to your work. However, it’s also very deeply rooted in the urban setting. How do you combine your connection to the natural imagery with the urban landscape and environment that your work has to exist in?

Sou Fujimoto: Wow, yeah, it is nice to work with such different urban situation. Of course, Tokyo has such a specific urban condition, but for example, recently we started doing projects in France, sometimes in Paris and sometimes out of Paris and then differen different situations arise. And of course, the climate conditions are so different. As a basic inspiration I have the relationship between nature and architecture, but every time it depends on the different conditions.

This is a nice point because I don’t want to push my thinking too much to different areas, but I like to have inspiration from different situations, different cities, different locations, and then it’s like a mutual interrelationship could make something unexpected. For me, that is the important part of the creative activities.

ICON: You’ve spoken before about making landscapes rather than buildings, but architects usually prefer to think about buildings rather than landscapes…

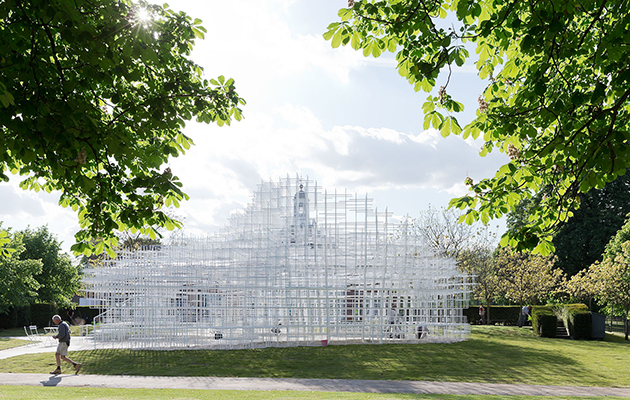

Sou Fujimoto: When we designed the Serpentine Pavilion, it was in the park, and it was in a place where people like the public spaces, but it’s not so big. I like to create such diversities of the behaviours of people. And then, I thought if it is like the extension of the landscape, extension from the park or the new types of landscape, then it could have more potential to allow people to choose their own places or do something different from their normal daily life. That was the inspiration, so the architecture as landscape is really relating to people’s behaviours, for me.

The 2013 Serpentine Gallery Pavilion by Sou Fujimoto. Photo: Iwan Baan

The 2013 Serpentine Gallery Pavilion by Sou Fujimoto. Photo: Iwan Baan

It’s like we don’t have to distinguish so much between the buildings and the landscape because it’s already melting together. If you make the spaces in a different way the divisions between architecture or buildings and landscape is not so important. It’s more exciting to treat the landscape things, architecture things, and maybe even the furniture, and integrating them together to create the place or field for people in that sense. That is, I think, the crucial thinking.

ICON: How has the nature of your work changed over the course of your career?

Sou Fujimoto: That’s quite important. Of course, in my childhood days I was playing around in the forest because of my hometown was such a nature field. When I moved to Tokyo to learn architecture, it made me re-understand the contrast of the city and the natural forest. And I found that the Tokyo has certain artificial landscapes, but it’s not so different from the forest. Yeah, of course the appearance is completely different, but in Tokyo you feel you are surrounded by many small pieces, especially in residential areas as you walk around. It’s like creating human scales, but still it is not like a closed environment, it’s quite open, you can choose your own way to walk around meandering in the city. And in the forest is the same: small trees, large trees are surrounding you to create the human scale. And then of course, you can choose your own way, so the basic structures behind the appearance is surprisingly similar.

And that was kind of an amazing moment that I found, the architecture or architectural environment and the natural environment could have similarities and we can deal with both of them in a equal way. That was the starting point, and after that I tried to create possible different ways of integrating or mixing them and so on. And then, step-by-step our understanding of the nature or the way to deal with the nature is developing, but it’s not linear, it’s more like spreading, in a sense.

Mille Arbres proposal in Paris by Sou Fujimoto Photo: SFA/OXO/Morph

Mille Arbres proposal in Paris by Sou Fujimoto Photo: SFA/OXO/Morph

Icon: You come from a small-scale architecture background, designing houses in really small plots in Tokyo, but now you have access to huge projects. However, lot’s of your work still plays with this sense of scale…

Sou Fujimoto: Before I couldn’t imagine how I could deal with those kind of bigger scales, but step-by-step we got there. Everything is based on the people’s life and that is always the same size; a private house size is 50 sq m or 80 sq m for two or three people. If you just base on those fundamentals to think about the people’s life, people’s interaction to the spaces or interaction between people, working with large-scale projects is not so different. At the same time it’s quite exciting to see how we can reinvent some of the elements of the architecture.

For the private houses, for example, the wall or meaning of the wall could be redefined in a sense or the meaning of the window should be redefined with some new ideas, and then the whole architecture itself is completely new.

The Serpentine was quite good example. We tried to redefine everything in architecture. Structures, furniture, scales, and different architecture scales inside and outside, all those kinds of elements are redefined and rethought. In the end everything is completely different from normal architecture, but still it’s a nice space for people to be in.

L Arbre Blanc by Sou Fujimoto is under construction in Montpellier. Photo: SFA/NLA/OXO/RSI

L Arbre Blanc by Sou Fujimoto is under construction in Montpellier. Photo: SFA/NLA/OXO/RSI

The way we treat those kind of big volumes relating to their surroundings, is so different from the small houses, so every time we try to rethink what it is, bigger things or smaller things, people’s life or treatment of the façade, but which point to always rethink.

And of course, if you rethink everything in really such a huge scales that must be really crazy amazing things, but it depends on the actual conditions. We can find the crucial point of the project and try to change it, transform it into new things. And finally, even the bigger project, the whole values should be changed.

And in case, for example, is the Montpellier housing project. It is, in a sense, quite a normal topology. It’s a housing block with balconies, so it’s almost the same as a typical normal boring housing; but then we added the larger scale on the balconies making them stick out so much and then placed the balconies all around. These decisions depend on the climate conditions, depends on the locations, and then finally as a whole it is something completely new.

Futures of the Future runs from 22 June to 05 August at Japan House London