|

|

||

|

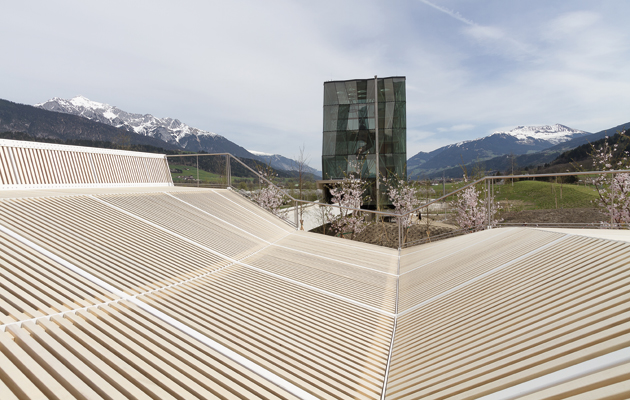

The Norwegian architect gets in touch with its inner child to create a six-storey glass playground at Swarovski’s curious Alpine tourist attraction As an architect, how do you approach a project when you know the results will be upstaged by the crystal eyes staring out of a huge earthen head? And when your client – cut-glass giant Swarovski – has an obsession with “engineering crystalline poetry”, proclaiming at the opening that “dreams are so often out of reach: here, at Norwegian practice Snøhetta has been remarkably savvy in maintaining its status as a critical darling across the fields of architecture and design. As such, it must have been a relief that Swarovski turned out to be a rather more pragmatic, even hard-nosed, client than its flowery rhetoric might suggest. In 1995, the firm invited polymathic Austrian artist André Heller to create a green mound housing five darkened “wunderkammers” at Wattens, its historic manufacturing base deep in the Tyrolean Alps. The results – a Buckminster Fuller dome, a mechanical theatre of deconstructed mannequins by Jim Whiting and more, all lumped together with a bit of company history in a rickety concrete shell – were a bit ropey, particularly when banged up against industrial facilities. But the allure of Heller’s pièce de resistance – the otherworldly 17m-tall head on the mound’s exterior – combined with the breathtaking mountain landscape and the firm’s rapid global expansion, were soon reeling in over 600,000 visitors a year. Unexpectedly, Swarovski found itself hosting one of Austria’s top tourist attractions: Kristallwelten. Despite the gradual accretion of artwork in and around the site, a more emphatic, and encompassing, spectacle was required to meet the expectations of the growing band of crystal devotees – younger visitors in particular were often underwhelmed by the existing offering. A goal was set of doubling the length of visits and increasing total numbers by a third. Snøhetta was tasked with catering to the needs of children and diners – landscaping, entrance facilities and retail were largely left to others. The wunderkammers were refreshed, embracing the dreams of a new crop of big-name artists and designers, including Lee Bull, Fredrikson Stallard and Studio Job. Despite their best efforts, it seems unlikely that their fantasies will put paid to prepubescent apathy. Snøhetta’s solution was to invent a brand-new (mini) typology. There was an understandable reluctance on the part of Swarovski to upstage Heller’s green god, but permission was eventually granted to build a 20m-tall, six-storey glass tower behind the mound: a massive, gravity-defying playground that can house up to 120 children. This slightly wonky structure – its facetted exterior gently mimics the faces of a crystal, without the fidelity that can beset Swarovski commissions – is entered at the first floor by a walkway. |

Words John Jervis

Above: The vertical playground viewed from the climbing frame |

|

|

||

|

A rope mesh climbs 14m up the height of the tower |

||

|

Each floor contains a single space, this one a children’s changing room. One wall is packed with a colourful cluster of pentagonal lockers – a nod to geometry, echoed in the large triangle of padded seating, the wall decorations that recur throughout the tower, hexagonal tags on the locker keys and so on. Behind the lockers is the concrete core with light steel stairs and a lift. The facades are constructed of 160 different Swarovski-manufactured crystal panels, all fritted with small, light-reducing animals in homage to the firm’s crystal collectables. Impressive views up into the mountains and across the valley below are echoed internally by a substantial wooden bulge curving down from the ceiling. The building is naturally ventilated courtesy of a significant vertical draft from hatches at its base to top-opening rooflights. Cooling is assisted by the activated concrete core and heating is fully integrated into the structure. This, according to the architects, is no-nonsense parametric design – every element is in a direct relationship with adjacent ones. Thus late alterations to the depth of safety cushioning resulted in significant design revisions. |

||

|

A sculptural restaurant in white concrete is reached via a copper-clad tunnel |

||

|

All the conventional patterns of play are present, from sliding and jumping to climbing and hiding, but stacked one above another. The bulge dropping from the first-floor ceiling is mirrored by one rising from the floor in the room above – a womb-like hiding place with an eye-like opening created by splitting the surfaces in two. Most dramatically, a taut octagonal mesh of rope climbs right up to the top floor, allowing the brave to scale 14m without interruption. Other floors boast an irregular forest of wooden swings; a curved, tubular slide reminiscent of a Carsten Höller installation; a jumble of circular trampolines; and shape-changing mirrors. At the top, the climbing frame emerges into an unexpectedly airy space – the whole floor has been replaced by tight, flexible wire mesh, deconstructing the surface and allowing children to spring across its entirety. Viewed from outside, figures seem to float in the structure, irrespective of level, buoyed by excitement. Nearby is a more conventional, if still eye-catching, external playground. A 23m-long climbing frame of light-wood slats undulates in a skeletal fashion, sometimes gently, sometimes at unexpectedly steep gradients. It is equipped with a slide, clambering nets, ropes and more, as well as a neat hole to allow a young birch sapling to mature. A maze of walls underneath is punctured by peepholes and crystals, and dotted with playground paraphernalia. The interactive concrete water feature beyond, with blue-and-white mosaics, adjustable water spouts and twisting wooden elements, proved beyond my comprehension. |

||

|

One floor of the tower contains a forest of wooden swings |

||

|

A ground-hugging pavilion, with a curvaceous, bone-like structure in porous white concrete, has been built to house the restaurant. Entered by a copper tunnel – calculated to age, thus providing luxury without accompanying gaucherie – the interior is distinguished by its panoramic views across Kristallwelten (with the factory carefully hidden from sight). The matt textiles and stained oak of the angular seating structure that divides the room are smokey and attractive; the accompanying Philippe Starck chairs in a rosey copper rather less so. Snøhetta has also designed an elegant new back-of-house structure – a long rectilinear structure in light concrete, clad in a local spruce on one side, that shields the visitor attraction from the car park, making sensible use of the site and providing generous natural light to the kitchen. Finally, a winding tunnel of glowing white fibres against angled black wooden panels, accompanied by vaguely crystalline interactive acoustics, penetrates deep into Heller’s mound, providing an alternative access route to the shop. |

||

|

One floor of the tower is equipped with circular trampolines and shape-changing mirrors |

||

|

In the face of adages about never working with children, animals and family firms, Snøhetta has, perhaps surprisingly, found a receptive and generous client in Swarovski, with a finite but sufficient budget. As a result, the project took only three years from start to finish, and Snøhetta was allowed to focus on users and landscapes rather than crystals and retail. The outcome is a new landmark that places children at the centre of the experience. Snøhetta’s previous involvement in this field – one kindergarten ten years ago – has been limited, yet it has devised a building inhabited by life and light, in total contrast to the dark wunderkammers alongside. Time may be required to fully gauge the tower’s success, and sulky teenagers may still find little to their taste at Kristallwelten. However, if younger children do prove unreceptive or accident-prone, they should be castigated for ingratitude and fragility. For a practice as lauded as Snøhetta, this sort of mid-sized undertaking now acts as little more than a diversion – stimulating research fodder rather than meat and drink – yet its solution is still masterful. It’s almost irritating. |

||

|

A tunnel lined with glowing white fibres leads visitors into the shopping area |

||