Built in the 1960s, the Seattle Space Needle is slated for a high-tech renovation. Photo: Victor Grigas

Built in the 1960s, the Seattle Space Needle is slated for a high-tech renovation. Photo: Victor Grigas

Seattle’s Space Needle was a blast from the future stymied by 1960s material shortages. But with the discovery of original drawings, John Graham’s space-age vision is becoming a 21st-century reality, writes Crystal Bennes

In the spring of 1959, while on holiday in Stuttgart, hotel executive Edward Carlson booked in for a meal at the restaurant located on top of the city’s brand-new TV tower. There, dining 200m above the streets, he had an idea that would change his native city of Seattle forever. For Carlson, in addition to running a large hotel business, was also chairman of the 1962 Century 21 Exposition. Realising that Seattle would need a striking symbol of its own to ensure the Expo’s commercial and critical success, on returning home, Carlson drew a simple sketch of a tower topped with a disc – inspired in part by Stuttgart’s TV tower – and presented it to the Expo board. Thus, the Space Needle was born, as in so many often-apocryphal architectural origin stories, as a back-of-the-napkin sketch.

Fifty-six years later, and the structure created thanks to Carlson’s sketch is deemed worthy of a $100 million upgrade, work on which began last year. The Space Needle has become a visual shorthand for Carlson’s hometown. Without it, the Seattle skyline could be anywhere, another non-descript city. In photographs where the Space Needle has been removed, local residents hardly recognise it. The Space Needle gives the city, perhaps not a purpose, but certainly an identity. Of course, it wasn’t always this way.

Seattle’s 1962 World’s Fair was the first to be held in the US that incorporated a component of a pre-existing city plan. It was an earlier fair, the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific (AYP) Exposition held in Seattle in 1909, that helped give birth to the notion of city planning in a town that had hitherto been a major transportation and supply centre for Alaskan miners. One year after the AYP, the city created a Municipal Plans Commission, but the 1912 development plan created by civil engineer, Virgil Bogue, was ultimately rejected by voters. Some five decades later, in 1955, voter approval was finally secured to construct a civic centre, a key component of Bogue’s original city plan.

After four decades, the Space Needle still dominates the Seattle skyline. Photo: Kerry Park

After four decades, the Space Needle still dominates the Seattle skyline. Photo: Kerry Park

The approval for the construction of the civic centre was a key catalyst for the 1962 fair. Local philanthropists agreed that the most appropriate way to celebrate the link between the AYP 50 years prior and the soon-to-be-constructed civic centre would be to stage another grand exhibition. Consequently, the complex would fulfil two different functions – its permanent life as Seattle’s civic centre, as well as its temporary life as an Expo pavilion. Century 21, as famously described by fair president Joseph Grandy, would be the first ‘convertible fair’ where the purpose-built civic centre, arena, monorail, opera house and science pavilion would be converted to permanent use when the fair ended.

And although the immediate impact on the Expo’s chosen site – a disused area next to the commercial downtown – was significant, the view of Seattle from above provided by the Space Needle also helped to fast-forward urban planning change across the city. Writing in the Manchester Guardian in April 1962, broadcaster and reporter Alistair Cooke criticised the ‘grasping publicity’ of this ‘second category fair’ and, his implication suggests, a second category city as well. The Space Needle offered visitors a new perspective on a city not worth looking at. ‘When the fair is dead and done with, it will offer the town’s citizens a godlike view of the grandeur that begins on the horizon and mocks the rather dreary works of man below – the sprawling freight yards and waterfront and miles of junk and secondhand car lots.’

Although local reaction to Cooke’s criticism was frosty, one imagines Seattle’s city planners felt similarly upon seeing their city from above for the first time. As Seattle historian, Knute Berger outlines in his 2012 book, Space Needle: The Spirit of Seattle, the Expo also initiated sweeping changes in urban infrastructure outside the fairgrounds. During the fair, the city completed its downtown freeway, and a new floating bridge was built to forge a link to suburban Redmond. Most notably, however, the area around the city’s waterfront began its transformation from a working port to tourist attraction. Space Needle architect Victor Steinbrueck was also later instrumental in saving the city’s other famous landmark, Pike Place Market, from demolition and redevelopment in the late 1960s.

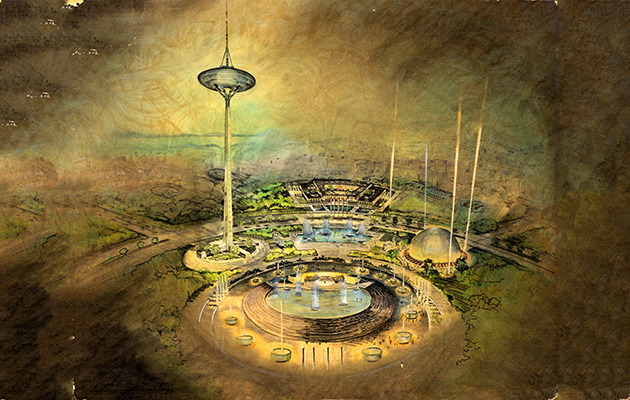

Proposed version of the Space Needle, artists rendition Century 21 Exhibition ca. 1962.

Proposed version of the Space Needle, artists rendition Century 21 Exhibition ca. 1962.

The legacy of Century 21 urbanism on the waterfront continues today with the replacement of the Alaskan Way Viaduct – an elevated, double-decked highway, which opened in 1953, cutting the waterfront off from the city – with a road tunnel. Following demolition of the viaduct, James Corner Field Operations, co-designers of New York City’s High Line, are set to redesign the opened-up waterfront as a landscaped public realm.

Meanwhile, the Space Needle is getting its own multimillion-dollar renovation, led by architect Olson Kundig. Despite the fact that the tower was over-engineered to withstand 200mph winds and a 9.0 earthquake, at a cost of $4.5 million (including operational costs during the Expo), building technology and standards have evolved such that it is due an upgrade. Last year, construction began on the ‘Century Project’, the largest investment in the Space Needle since it was completed. Providing both an engineering upgrade and aesthetic remodel, the Century Project will see the observation deck enclosures and the restaurant floor replaced with glass.

Contrary to popular opinion, the city of Seattle does not and never has owned the Space Needle. To ensure completion in time for the Expo’s opening, it was privately funded with no bidding process. The project was paid for by a consortium including the building’s original architect, John Graham; Bagley Wright, a former New York newspaper journalist; shipping heir, David Skinner; Norton Clapp, chairman of the Weyerhauser Corporation; and engineer Howard S Wright. Wright’s family are now the sole owners of the structure. And yet, despite private ownership, the Space Needle’s 1999 designation as an official Seattle landmark means any changes to the exterior must be approved by the city’s Landmarks Preservation Board.

Space Needle artists conception Seattle Worlds Fair 1960; the final design was hit by material shortages.

Space Needle artists conception Seattle Worlds Fair 1960; the final design was hit by material shortages.

Alan Maskin, project lead for Olson Kundig, explains the changes as a return to the minimal qualities of the original design. ‘Many cumbersome additions were made in the 1970s and 80s, particularly in the observation deck enclosure,’ Maskin says. ‘Subtraction is far more important than addition as we’re trying to reveal the underlying structure.’ In their quest to reveal this structure, Maskin and his team also made an intriguing discovery: early renderings of the tower that shed new light on how the design was originally conceived.

Following Edward Carlson’s initial sketch, the reins were taken up by local architect, John Graham. After working up unsatisfactory designs for nearly a year, Graham hired the younger Victor Steinbrueck to inject space-age excitement into his lacklustre project. Inspired by a shapely abstract sculpture by the artist David Lemon, Steinbrueck retained Graham’s flying saucer, but pinched in the tower for a distinctive wasp-waisted look.

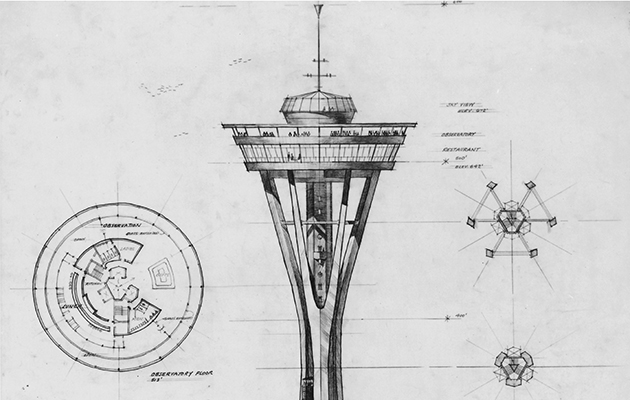

While searching the archives of Graham’s office (purchased in 1986 by another Seattle-based practice, DLR Group), Maskin and his team discovered the original renders. Unlike the partial glazing of the current observation deck, these show the deck with floor-to-ceiling glazing. Maskin suspects a materials shortage at the time led to an amendment of the final design. ‘There was a big construction boom in Seattle in the early 1960s with many contemporary articles written about the difficulty of obtaining glass because of all the construction,’ he says. ‘So, in one sense, we’re fulfilling Graham’s original vision for the Space Needle.’ The renders ultimately helped to convince the Landmarks Preservation Board that while an all-glass observation deck may have been modern, it was also in keeping with the intentions of the original architects.

An early rendering by John Graham was recently discovered, suggests floor-to-ceiling glazing was intended.

An early rendering by John Graham was recently discovered, suggests floor-to-ceiling glazing was intended.

The flying-saucer top and extensive use of glass may have suggested a futuristic feel, such aesthetics were firmly entrenched in contemporary politics. ‘The Space Needle would not exist but for the Cold War,’ writes Berger. The 1957 launch of the Soviet satellite Sputnik into orbit had prompted a rush of US national government interest in funding for science and science education. If the Seattle fair organisers wanted federal money, Berger recounts, they were told they could only obtain it for a science-themed fair. Once that decision was confirmed, a space-age theme seemed obvious, an opportunity for the US to present its own vision of the future in contrast to Russia. In what was to be an otherwise modest expo, the Space Needle emerged as ‘a physical representation of the space age and science’.

If Olson Kundig has set out to return the Space Needle to something approaching Graham’s original, space-age vision, the renovations are nevertheless firmly situated in their 21st-century context. The works will replace glass windows with floor-to-ceiling glazing and the wire safety cages on the observation decks with glass safety barriers. Yes, it’s streamlined and minimal, but it’s also clearly intended to be catnip for the Instagram generation. This is confirmed by Maskin when asked about the commercial pressures of the remodelling. ‘Although the Space Needle is the symbol of Seattle, it’s also a privately-owned structure,’ he says. ‘One which is expensive to maintain and upkeep and it needs to pay for itself.’

The Space Needle materialised amid Cold War political one-upmanship, a symbol of aspirational American capitalism in contrast to Russia’s communist alternative. Of course, as per the broader aims of the Century 21 Expo, it was also a means of attracting investment to Seattle. Now that capitalism has supposedly triumphed and the city has certainly succeeded in attracting investment (perhaps most noticeable in the recent Amazon-driven building boom), the Space Needle must still justify its existence on capitalist grounds. But these days, rather than seek national investment to remain operational, it looks to the power of social-media-driven tourism. One imagines that’s a strategy which Carlson, the hotelier, would have understood all too well.