|

|

||

|

This year’s British Pavilion was FAT’s final project. Here, founding director Sam Jacob recalls how the practice trawled archives and attics to piece together the history of British modernism, and attempt to reclaim it for the present day This is an article from Icon’s August 2014 issue: Venice Biennale, which was published under the headline “Building Jerusalem”. Buy the magazine from 3 July and subscribe to the magazine for more It was a sunny day with the huge 1970s estate of Thamesmead ranged out in the landscape, swans and horses in the distance, the famous vista captured by Stanley Kubrick in A Clockwork Orange in the foreground, its cinematic image partly clawed away by diggers. The British Council had just issued its open call for the 2014 Venice Biennale, asking for research into the history of British modernism. A decade earlier, in another postwar new town across the North Sea, I had worked closely with Crimson Architectural Historians, a group whose own fascination with how to use history in the present had been incredibly significant for both myself and my practice, FAT. Their WiMBY! (an acronym of Welcome Into My Back Yard) project in Hoogvleit in the Netherlands used historical research as a propositional device, embedding them within the community, local politics and development plans.

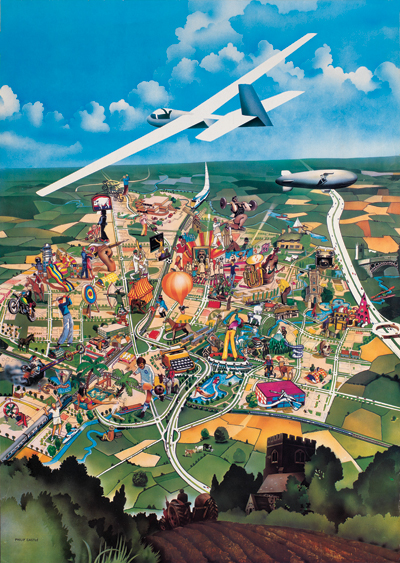

Leisure in Milton Keynes, Philip Castle, 1971 And they had acted as our client for a park and cultural centre full of social and civic ambition. The Heerlijkheid, as it became known, was a tangible response to the realities of postwar planning. But it had, partly due to its long gestation, generated long, deep and wide-ranging discussions. Venice, it seemed, could provide the perfect armature to finally give bones to the flesh of this discussion. In other words, it could act as retroactive theory for the Heerlijkheid. But our ambition was more than this. Here was a chance to wrestle the history of British architecture out of its mired, tired and partisan position. The opportunity seemed so good that we certainly couldn’t let anyone else win the pitch. Our already grand plan then took a dramatic turn when we broke the news that this was to be the final FAT project, that we were “breaking up the band”. Venice would be our parting gift to architectural culture. A show that wasn’t about us but was about the world that we’d emerged from, a retelling of history that might, in passing, suggest that we’d been right all along, that FAT was the inevitable historical product of centuries of British architecture.

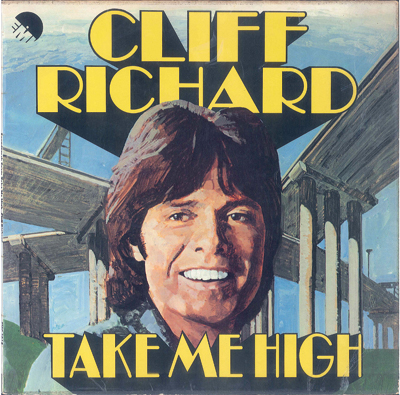

Cliff Richard album cover, 1973 So, this year’s British Pavilion exhibition, A Clockwork Jerusalem, was born. It emerged out of personal obsessions, hunches and longstanding conversations to address curator Rem Koolhaas’s theme of Absorbing Modernity. These obsessions and interests soon found themselves dangling from a string stretched across the office that became known as “the washing line” – a lo-fi repository print-outs and photocopies, low-res jpgs and screen grabs, placeholders and lines of enquiry held together with knots and paper clips, endlessly juggled and rearranged. These days, research takes on a strange character. Armed with a Google search box, you can find so much, so fast. You can read around things, find connections and possibilities. But they remain at the same low resolution as the stacks of images you download. The process of analogue research is almost entirely opposite. Slow – tortuously slow – but super-high resolution. We delved into archives of very different kinds: personal, governmental, social. We emailed, phoned and schlepped around. And as we did, so our fascination with material grew.

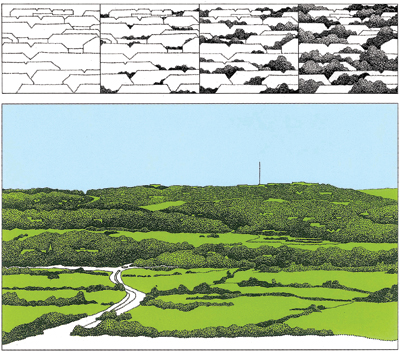

Milton Keynes Forest City, 1971 From the Sir John Soane’s Museum to the Stanley Kubrick Archive, from long car journeys with Milton Keynes’s chief architect Derek Walker to negotiations with the Archigram archives, from service passages in the bowels of the Barbican to the rarely troubled Cumbernauld section of the North Lanarkshire Archives, from working on deals with music publishers to calling in favours, the research process exploded disciplinary boundaries as we had hoped. Gruelling for sure, but also rewarding. Stuck in a traffic jam with Walker was a great chance to press him on how ley lines and sewage works had come together in Milton Keynes. Opening Kubrick boxes in the special collections room at the London College of Communication was incredible, with letters, notes, photographs and other ephemera jumbled up together. Trying to get permission to use the location-scouting pictures of Thamesmead proved a perfect excuse to ask the producer of A Clockwork Orange why exactly the estate had been chosen. The generosity of Archigram’s David Greene helped not only to leverage something out of the group’s fabled storage shed in Southend but also to illuminate some lesser known sides of its output. Trying to convince photographer Kevin Cummins of the relevance of an architecture biennale to his work prompted an insight into the moment he took the iconic images of Joy Division on the bridge into Hulme. Tracking down the artist behind a flyer for a new-age travellers’ party, also in Hulme, brought forth an evocative letter about the wild parties they once held. Tea with former New Society editor Paul Barker in his north London home was a view into a moment in the late 1960s when radical architecture and sociology were comfortable bedfellows.

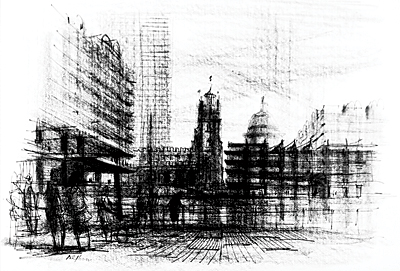

Barbican redevelopment, Norah Glover, 1964 And then there was eBay, thank the Lord. It’s incredible how much of the fabric of the show was ordered from the attics and stores of the world: old Walkmans, late Victorian books, early 1980s records, souvenirs all came bubble-wrapped and jiffy-bagged. These were moments of musty-pleasure: unwrapping the Cliff Richard’s Take Me High to reveal his face glowing with the ecstasy of modernity under Spaghetti Junction. Ebay is surely the future of museology. And no doubt a form of archeology in itself, a way of unearthing fragments of lost civilisations with a PayPal account. The idea of a national pavilion is a strange anachronism in an age where state seems to mean less and less – and all the more so when it is clustered with the French and Germans in a corner of the Giardini that seems marooned in the 19th century. The challenge was to tell a story that was both internationally relevant and retained a significance at home; and equally one that was both historical in content and detained a significance in the present. These became the questions of how to put the show together and how to frame its argument. How, in other words, to edit and articulate narrative. The pavilion’s central feature had been around since almost the very first sketches, a mound that was evocative of not only neolithic earth formations, but also the slum-clearance rubble piled to form landscaping at the heart of social housing and the soon to be demolished mound of Robin Hood Gardens. Around this, we built a panoramic view of the story of British modernity, and in the smaller pavilion rooms, thematically led groupings exploring ideas and projects.

Concrete cows, Liz Leyh, 1978, on loan from Milton Keynes The exhibition, however, was just one way that the narrative of A Clockwork Jerusalem could have been articulated. We spent considerable time during the process talking to journalists, to politicians, to clients and agencies both to help gain a purchase in the world outside of the bubble of the biennale and to toughen up our own position. After all, our true ambition was to make an idea that could have some contemporary use beyond the boundaries of the pavilion itself. A week after the glamour and excitement of the vernissage, I was back in Thamesmead – this time at the end of a bike tour I was leading with others through the history of London’s social housing. Cycling from Arnold Circus, through the Lansbury Estate and then all the way out on the Thames path was a journey through the show’s landscape. Now, gathered on the side of Southmere Lake as Dan Hill from housing association Peabody explained to us the possibilities and problems of Thamesmead’s future, the narrative of A Clockwork Jerusalem seemed even more pressing. In the midst of the current crisis in our built environment, a crisis formed by the fluidity of capital and monetisation of the city, are there ways in which the real spirit of British modernity might help us? In truth, that’s our deepest and dearest held hope for the show – that it (and we) might bridge the gap between history, pop culture, polemic and real practical work.

|

Words Sam Jacob |

|

|

||