|

|

||

|

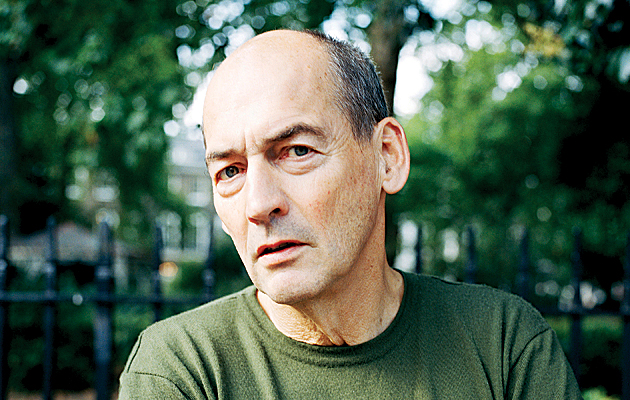

Rem Koolhaas thinks that too little attention is paid to the countryside, where change is happening at a faster rate than in most cities. In this illustrated essay by Koolhaas on the rural world, the OMA founder argues that architects need to take stock of a new agricultural revolution Over the past 10 years, I have been collecting documents and insights about a previously neglected subject – the countryside. Read more: Rem Koolhaas on urban mobility and the future of transport I have been frequently travelling to a Swiss mountain village in the Engadin valley, and throughout the years have been able to actively observe a number of changes.

Initially we did not think to look for a pattern, but in the end the pattern became almost inevitable. It epitomises many of the changes underway in the European countryside.

This is how big the village was when I first went there 20 years ago. Since then, the village has become completely depopulated. Its original inhabitants have left, and yet the village is 2-3 times bigger. This was the first paradoxical issue: how can a village that depopulates, grow and multiply at the same time? The countryside is inhabited in a more provisional way. It can be defined as a process of “thinning” – an increase in the area covered alongside a diminishing intensity in its use. As we looked further to understand the changes, interesting developments were revealed.

This was the authentic architecture of the village. All the rules this architecture follows aim at maintaining this authenticity – they constitute a very vigorous attitude to preservation, with strict rules for maintaining the heritage of original buildings.

Today you find this house next door, formerly a barn, renovated in a traditional style. It strictly follows all the rules of preservation, yet it is a completely different kind of creation. It constitutes a kind of modernity that we have never encountered before.

If you look between their curtains you see the typical contemporary style of consumption – minimalism, but with an exceptional amount of cushions, as if to accommodate an invisible pain.

We are trying to understand what has happened in the century between Prokudin-Gorsky’s photograph of the three women in the Russian countryside of 1909, and the scene in the Swiss village square today, illustrating a radically different condition … This was the countryside 100 years ago, demonstrating a highly ritualised localism.

This is the countryside now – three south Asian women brutally imported to look after the pets, the kids and the houses.

Looking further, you find that this Swiss meadow is no longer maintained by the Swiss but by imported labour from Sri Lanka.

At first this appears to be a factory worker in India, but in fact he is working on a milk farm in Italy.

To test our hunches about the transformation of the countryside, and to see what those in the countryside who are not farming are actually doing, we made an inventory of a 12x3km strip of rural Holland, 16km north of Amsterdam. What we found was a thriving prototype of the non-agricultural countryside – a new genre of land use called “the intermediate” – a well-manicured place where surface appearances bear almost no relation to what is actually happening on the land and in the buildings. |

Words Rem Koolhaas

Images: OMA; Time; John Deere; AG Technology; lely.com; Library of Congress |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Our chosen strip is bordered in the North by Stad van de Zon, a new sustainable suburban expansion; in the South by a fort in the Amsterdam Defence Line, a Unesco World Heritage site; in the east by the Beemster Polder, also a Unesco World Heritage site; and in the west by farmland. Inside these coordinates we started to uncover Intermedi-stan, a land of the in-between. The strip is undergoing two simultaneous and contradictory mutations. On the one hand, farmers are diversifying. The second mutation is the influx of urbanites wanting to sample life in the countryside, attracted by the aura of authenticity. These two wrenching trends create the landscape of the intermediate.

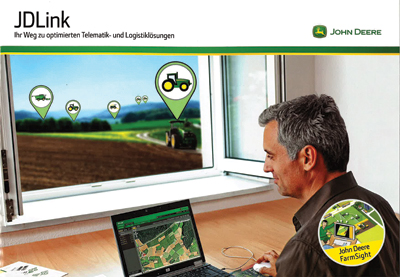

Husbandry of the land is now a digital practice. For example the tractor, which revolutionised the farm in the 19th century, has become a computerised work station. It is a series of devices and sensors that create a seamless, yet detached digital interface between the driver and the earth. The countryside in terms of how we work is becoming very similar to the city. The farmer is like us – a flex worker, operating on a laptop from any possible location.

Dairy farming and animal husbandry are also increasingly automated – milking, feeding, barn cleaning and dung removal are digitalised and taken care of by robots. This is not to say that it is all bad. It is only ironic that such drastic transformations are barely on the radar in our education and thinking.

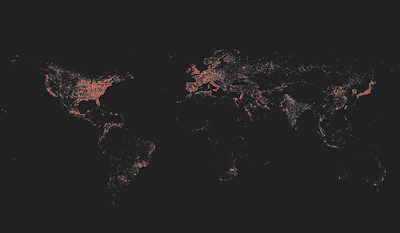

Based on these observations, we began realising that there is a totally new condition taking place in the countryside. Yet practically all our attention goes to the red (urbanised) areas which physically constitute a very small part of the world. In architecture books we are bombarded with statistics confirming the ubiquity of the urban condition, while the symmetrical question is ignored – what are those moving to the city leaving behind?

The rest, a significantly larger section of the world, falls under neglect and lack of knowledge. However, it is subject to the same market forces encountered in cities. You could therefore see the countryside as a place where people are disappearing from. In this void new processes are taking place and new experiments and developments are being made.

At this scale, agriculture is being increasingly submitted to the market economy and now this is the new state, a more digitalised landscape.

This new digital frontier is changing the way we understand even the most far removed environments and they are becoming better known than many parts of the city. There is a software, Helveta, that enables people in the Amazon to identify and track every single tree. Swathes of forest are now carefully inventorised environments and tribesmen are turned into digital infomers.

A colossal new order of rigour is appearing everywhere. A feed lot for cows is organised like the most rigid city and server farms are being hidden in remote forests and deserts – the countryside being the ideal situation for these types of conditions. Today, a hyper-Cartesian order is being imposed on the countryside, enabling the poeticism and arbitrariness, once associated with it, to now be reserved for cities.

The countryside is now the frontline of transformation. A world formerly dictated by the seasons and the organisation of agriculture is now a toxic mix of genetic experiment, science, industrial nostalgia, seasonal immigration, territorial buying sprees, massive subsidies, incidental inhabitation, tax incentives, investment, political turmoil, in other words more volatile than the most accelerated city. The countryside is an amalgamation of tendencies that are outside our overview and outside our awareness. Our current obsession with only the city is highly irresponsible because you cannot understand the city without understanding the countryside. We are now only beginning to increase our understanding of conditions that were previously unexplored – a process to continue further. This article was first published in Icon’s September 2014 issue: Countryside, under the headline “Koolhaas in the country”. Buy back issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this |

||