|

|

||

|

The 2014 World Cup in Brazil rekindled the debate about the legacy of global sporting events. But few people made the case for the aesthetic qualities of the stadiums – or the way that they have reclaimed the country’s modernist heritage What is the material legacy of a major sporting event? That is to say, what do the World Cup or Olympics leave us with other than arguments over whether we play more sport or not? What benefit, in terms of infrastructure and architecture, do these events bring, if any? Given that we are now in the early throes of what planners like to call the “legacy phase” of the most recent World Cup in Brazil and we are looking forward to the Olympic Games in two years in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil is an obvious place in which to see how some of the assumptions about legacy are playing out; it’s an even better site for an investigation into the term given that the World Cup has been held there before, in 1950. To put the recent, often violent, debate about this year’s event into context, we should look at the aftermath of the 1950 tournament, not only to see how sporting events can be used and misused but also to appreciate how much time needs to pass before their legacy can be considered. In 1941, the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig wrote a book called Brazil – Land of the Future. It was optimistic in outlook, but later prompted the joke during the days of military dictatorship and economic crisis that Brazil was the Land of the Future and always would be. Development in Brazil was slow. The Maracanã stadium, for instance, was built for the 1950 World Cup but not fully completed for another decade. Zweig’s confidence, however, was mainly founded on an positive reading of Brazil’s racial politics. “Brazil has shown up in the simplest way the absurdity of the racial problem that is destroying our European world; by just ignoring its alleged validity.” The Brazilian government in 1950 promoted football, as well as samba and carnival, as anchors of Brazilian identity and an integral part of this “ignoring”. This instrumental use of football by Brazil’s political leaders to create a sense of national identity was widely regarded as a success, despite the country’s humiliating defeat by Uruguay in the 1950 final, even more disastrous than its drubbing by Germany this time around. However, a nation’s identity obviously cannot be forged by sport alone. Brazil’s history since 1950 has been a long struggle by its people to throw off dictatorship and consolidate democracy. Yet, even so, so much of the 2014 World Cup was a revisiting of that other World Cup over 60 years ago. The Maracanã stadium in Rio was built for the 1950 World Cup but not fully completed for another decade. It is one of the best stadiums in the world – rather grandly dubbed “Templo sagrado no país do futebol” (the holy temple in a land of football), a name that seems to underline the Brazilians’ belief that they are somehow entitled to victory. The famous concrete ribs and bands on the facade have been restored, and more importantly the ramps and densely planned sports park in which it sits have had an overhaul, as this will also be the heart of the Rio Olympics. Jörg Schlaich, engineer of the Munich Olympic stadium, created an innovative scheme whereby existing concrete columns were reinforced to support a new horizontal spoked-wheel structure covered with a PTFE coated fibreglass membrane. It is a stunning building, establishing an aesthetic of refurbished mid-century modernism with high-tech flourishes that recurs throughout the event. |

Words Tim Abrahams

Illustrations Martin Nicolausson |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

This refurbishment of a significant piece of cultural patrimony has to be considered in counterpoint to the huge protests directed at Fifa before the World Cup. It should be remembered that the common cry was not to degrade the construction and refurbishment of stadiums but to build “Fifa-standard schools”. Romário, the former captain of the Brazil side, now a senator, cited the stadiums in a demand for improved infrastructure across the board. He asked how Brazil could afford “first-world stadiums when we cannot afford first-world hospitals and schools”. Brazil’s public investment in education increased between 2000 and 2010 from 3.5 per cent to 5.6 per cent and healthcare spending per capita doubled between 2002 and 2011 to put it on a par with Chile. The effect of the stadium-building programme was to raise standards and expectations across the country. Brazil wasn’t forced by Fifa to host the event, as critics such as the journalist Simon Jenkins have argued. A democratically elected national government bid and won the right to stage it. Fifa has been held responsible for many Brazilian problems, for which it isn’t necessarily responsible. The fact that Fifa takes all the profits from televising the event is ridiculous, but there is little to make it reconsider this unless the number of nations bidding for an event drops to one. For Brazil, the purpose appears to have been simply to host a world-class event. Part of the programme – certainly the part that touches architecture – was the attempt to rediscover and refurbish some of the key buildings in Brazil’s recent history. Nothing sums this up better than the Mineirão stadium in Belo Horizonte, which sits on the banks of the Lagoa da Pampulha, an artificial lake created by mayor Juscelino Kubitschek in the 1940s. Built in the early 1960s to plans by Eduardo Mendes Guimarães Jr and Caspar Garetto, the Mineirão was refurbished for the 2014 World Cup. The area around the Mineirão is the cradle of Brazilian modernism. Kubitschek’s association with Oscar Niemeyer, which would culminate in the construction of the national capital Brasília during Kubitschek’s presidency, began here when they were both forced to defend the parabolic concrete shell of the church of St Francis of Assisi in face of criticism from the church authorities. The stadium is another of the city’s architectural highlights, particularly the way that the structure’s coruna of concrete bulkheads rises above the wooded banks of the lake. Yet despite this, the Mineirão is often left out of critical histories, largely because it is a stadium. Perhaps fittingly, given the way the World Cup played out, the modernisation and renovation of the Mineirão was undertaken by a German team: Gerkan, Marg and Partners (GMP) and Jörg Schlaich’s firm, Schlaich, Bergermann and Partners (SBP). GMP was also the architect of the new roof of the Berlin Olympiastadion for the 2006 World Cup, and in many ways the refurbishment of the Mineirão reprises the same theme: the adaptation of a historic building to modern requirements. This brief has been performed with true architectural verve, a perfect example of how architects can contrast, interpret and underline the character of brutalist structures through adapting them. And, partly because the original Mineirão was a better building technically and artistically than the Olympiastadion, the finished project in Belo Horizonte far outstrips the work on the stadium in Berlin. A perfect example of this is the way in which the new stand roof starts out as an ultra-lightweight ring cable structure beneath the existing roof. Although the new compression ring and supports are a separate system, they closely follow the historic load-bearing structure. |

||

|

||

|

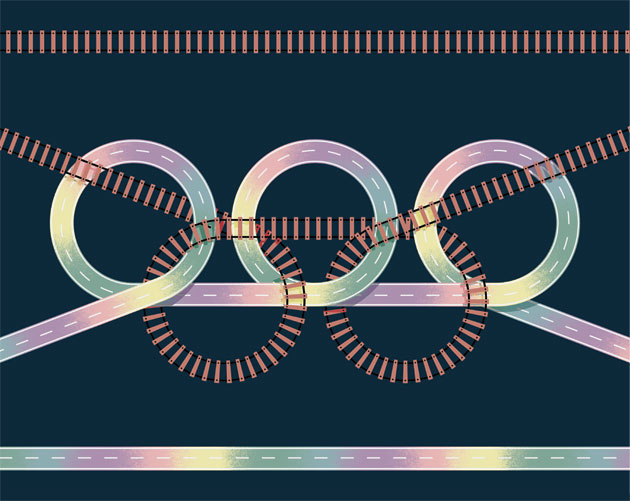

There seems to be a general reluctance to consider stadiums as appropriate sites for aesthetic endeavour. But consider the curved, criss-crossing truss that holds up the teflon and fibreglass roof of the Arena da Amazonia in Manaus – site of England’s defeat to Italy. Again built by GMP and SBP, it is inspired by a traditional Brazilian straw fruit basket, and at night it appears as an inflated pillow of light held down by a lattice. (The 7,000-tonne, X-shaped metal structural modules had to be shipped up the Amazon to Manaus.) Near the Arena da Amazonia stands the Teatro Amazonas, an opera house built by the rubber barons in the 1890s, which sat empty for much of the 20th century. It was only in 2001 that the Teatro Amazonas was granted enough funds for a permanent orchestra. Until that time, it was considered a glorious ruin. In the opening scene of Werner Herzog’s film Fitzcarraldo, an obsessive opera lover played by Klaus Kinski, arrives late at the theatre to see Caruso sing before commencing on an insane but ultimately successful plan to carry opera even further into Amazonia. It seems that in Europe we can countenance the romantic notion of a building representing an extreme aspiration if it is an opera house, but not if it is a football stadium. Of course, the programme for a World Cup is different to that of an Olympic Games. One is spread out across a country and focuses on a sport a large percentage of the population will never see the point of. The improvements to infrastructure will often not stretch beyond a lick of paint at the airport and new stadiums. An Olympics, on the other hand, has a huge impact on a very finite part of a single city. The very first modern Olympics in 1896 was predicated on what was described as an archaeological restoration but was really the rebuilding of the Panathinaiko stadium. Early games were hosted as part of international fairs which were engines to urban development throughout the early 20th century. A gold medal for urban planning was still awarded as recently as the London Games of 1948. Far from being a new idea, urban development and infrastructure is part of the modern Olympic DNA. The first competition in any Games is the Olympic bid. This is a race between competing city bureaucracies to present the most convincing plan for building and improving not just sporting but general urban infrastructure. The history of the Olympics is punctuated by the development of urban infrastructure. In 1908, London’s Central line was extended to Wood Lane to take visitors to the White City stadium. For the Tokyo Games in 1964, the city authorities did not construct many new sports facilities but did build two underground lines and established a central sewage authority for the first time. Why developments such as these cannot happen without an event says more about planning cultures than it does about the event itself. In 2005, Sebastian Coe took 20 children from the East End of London to Singapore and used them to convince the International Olympic Committee to award the Games to London. These children playing sport would be the Olympic legacy, he said. This helped him win the Games; it doesn’t mean that it was the real legacy. No event organiser will admit this, but there is no relation between providing world-class sports infrastructure and the playing of sport at a local level. It would be more honest of the London organisers to have claimed that the real legacy would be the memories of the event and an incredible urban park. The same goes for Rio’s organising committee. This last World Cup has produced particularly impressive work – new structures such as the ribbed Fonte Nova Arena by Schulitz Architekten as well as the refurbishments – a fact that has largely gone unnoticed in the pages of the architectural press. Architects should not be afraid to claim that beautiful buildings are the main legacy of sporting extravaganzas. This article first appeared in Icon’s November 2014 issue: Sport, under the headline “Post-match analysis”. Buy back issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this

|

||