|

|

||

|

In Vardø, an island at the most northeasterly point of Norway, Pritzker prize-winning architect Peter Zumthor and artist Louise Bourgeois collaborated on a monument to 91 witches burned at the stake in the 17th century I first see Peter Zumthor’s Steilneset Memorial to the Victims of the Finnmark Witchcraft Trials at night. The reclusive Swiss architect was visiting the small Arctic island of Vardø, close to Russia at Norway’s northeasterly tip, for a two-day conference on witchcraft. He also wanted to revisit his memorial, which opened at the end of June, without the incessant glare of the summer Midnight Sun. After a whisky-fuelled evening at the North Pole, the town’s solitary nightspot, we ascend a damp slope, passed abandoned boats and houses with cladding painted in primary colours, and the golf-ball dome of the US military radar installation, to negotiate the dark pathways on the outskirts of the fishing town. In February 2006, Zumthor visited for the first time this barren, windswept promontory, its jagged shoreline splintered by the crashing waves of the Barents Sea. “I was impressed by how many houses were dark,” he says of the declining, half-deserted port (population: 2,000). “I was walking around and I saw these buildings with lights placed in the windows as a sign that someone is at home. I thought that very beautiful. I saw some fish racks and the wide horizons. It’s important to me this horizontality of the landscape. And, when I woke up in the morning, I had the idea.”

You enter the House of Fire through a side passage Over the white picket fence of the local cemetery, in the light of a full moon, we see the 410-foot-long result of Zumthor’s inspiration, an extraordinary white textile cocoon suspended in an asymmetrical structure made of untreated pine that stands parallel to the shoreline. Inspired by the spindly local fishing racks on which cod are left out to dry, the textile core hanging inside the timber frame looks like the flayed skin of some huge beast. The hand-sewn sailcloth is pulled taut by steel cables to create a silhouette that resembles pointed teeth. Small windows are lit up, as if by candles, and echo the town’s lights on the other side of the harbor. You enter the Memorial Gallery via a wooden gangplank, one at each end of the structure, through a steel door, into blackness. The interior is painted in tar and has a ribbed ceiling, like the roof of an enormous mouth: one feels like Jonah in the belly of the whale. “In the summertime, when you go in and it’s dark, it’s even more surprising,” Zumthor remarks. There is a 5-metre-wide oak-floor corridor that runs the length of the interior and is attached to the timber frame by steel rods so that it doesn’t touch the textile membrane. Visitors have a firm footing, but the walls move in the wind, shuddering and snaking with heavy gusts. It took three years of engineering and 1:1 mock-ups at his alpine studio-home near Haldenstein, Switzerland (where 28 architects live and work with “no coffeeshops, no cinemas, just the cows around the corner” for company), to be sure that the structure could withstand the stormy Arctic conditions.

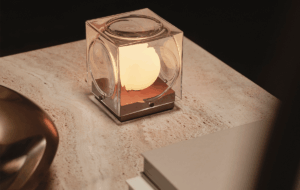

The memorial from the sea, with US radar installation in the background Ninety-one steel window frames positioned at varying heights funnel out on to the landscape, a swaying bulb in each of them, one for every witch that was burned at the stake here in the 17th century. By each window is the story of the witch that the bulb commemorates, reproduced from court protocols and printed on a piece of suspended silk. Accused of demonic conspiracy and of exerting magical harm by the casting of spells, they were thrown into the icy sea to see if they sank or floated (the latter indicative of their guilt), tortured on the rack or with hot tongs and, after they’d signed a confession, burned to death at this very spot. “Most of the victims [77 of them] were women,” Zumthor tells me. “The textile is stitched and the text inside is on silk. When the wind blows the space and the lights start to move and only you are on the ground. It’s made for this place; it’s very delicate.” “The space ends like this,” he adds, clasping his hands together, “It’s this dark space, fading out.” In an adjacent building, an austere black spiral-shaped box Zumthor built to house a posthumously realised installation by Louise Bourgeois – The Damned, The Possessed and The Beloved, one of the last she created – flames flicker brightly through 17 panes of smoked glass. The glass reflects the landscape and was inspired, Zumthor explains, by welding goggles. Inside is a steel chair, enclosed in a cone of concrete that has a rough splintered edge, over the seat of which dance five noisy jets of fire. Seven outsized mirrors on telescoping stands look down from above, reflecting and distorting the flames, like the faces of a condemning jury. “The fire is multiplying,” Zumthor says of this aggressive effect, “It’s like you’re in the fire.”

The House of Fire with Bourgeois’ installation In 2006, Zumthor was invited by Knut Wold, consultant and curator to the Norwegian Tourist Route – a federally funded scheme that has commissioned over 200 architectural projects along the country’s fjords, mountain valleys and coastline (observation platforms, rest stops, information kiosks and footbridges) – to build a pavilion to house an artwork by Louise Bourgeois. Zumthor, who was already collaborating with Wold on four museum buildings that cling to the rock face along the entranceway to an old Zinc mine in Sauda (begun in 2002 and due to open next year), had collaborated with Bourgeois in 2003 on an aborted project at Dia:Beacon in upstate New York. “I was extremely flattered to work with her again,” Zumthor says, “I was to build the shell for her art.” Bourgeois, who died in 2010 aged 98, was too frail to make the trip from New York to Norway and asked Zumthor to go there and report his impressions of the site. When he sent her his delicate watercolour sketches, which illustrated his initial idea, she declared his vision complete. After a few months she returned by fax a sketch of her own, more literal response to the witch hunts, and asked for a separate 7m square building to house an eternal “living flame”: “I offered to abandon my idea and to do only hers,” Zumthor says, “and she said, ‘No, please stay’. The result is really about two things – there is a line, which is mine, and a dot, which is hers.”

A wooden gangplank leads up to the textile core So, Vardø ended up with two memorials, costing £9 million, perhaps a little excessive for such a small, remote and impoverished town, but it’s hoped that tourists will make the pilgrimage there much as they do to see Zumthor’s best-known work, the cave-like Thermal Baths he built from locally quarried stone in the remote alpine village of Vals, Switzerland (1996). The memorial’s details, as one would expect from the 2009 Pritzker Prize winner, who trained as a cabinet-maker and began his career as conservation architect in the Department for the Preservation of Monuments, are exquisitely beautiful and well thought out, with a poetic and sensuous use of materials. When you look at his building in cross-section nothing seems arbitrary: “You cannot take a centimetre from any of the beams,” Zumthor notes of the wooden scaffold skeleton of his memorial. “Everything that is there is absolutely needed, and I think you can feel that.” However the two buildings have an uneasy relation to each other. The House of Fire looks like a visitor centre to the main attraction. “Normally I hate black glass,” Zumthor says, as we walk around the site the following day. “But it doesn’t look like a bank, does it?” “My main aim is to make emotional spaces,” Zumthor tells me over coffee in the town’s new cappuccino bar (an indication, he says, that things are already improving in Vardø). “To create not just a beautiful space but a space that touches me, that has emotional impact. As a boy, when I saw memorials of generals on horses I thought they were so boring. I tried to do everything possible here not to have a general on a horse, but an emotional space that brings you as close as possible to the historical dimension.”

The Memorial Gallery with its 91 windows and lights “When I look at [Peter] Eisenman’s monument it makes me so angry,” Zumthor says of the 2004 Holocaust memorial in Berlin, with its maze-like grid of 2,711 concrete plinths. “It’s still a block without a general, obstacles which could cause other aggressions” (swastikas are frequently graffittied on the stelae). He says he would have proposed a garden instead: “If 5 million people get killed, then I would do something which makes life go on. 5,000 oaks and free beer for the next 100 years for everyone in Berlin! That would be much better.” His moody memorial to the Finnmark witches is similarly intended to be “more about life and the emotions.” “I work a little bit like a sculptor,” Zumthor has explained of his working method. “When I start, my first idea for a building is with the material. What I learned early in my life is that the atmosphere created by architecture is informed by the way it surrounds the human body with physical presence … Architecture is something experiential, something that starts with the emotions.” Just before Zumthor left for the airport and the first of four flights back to Switzerland, we took an exhilarating ride in a rescue boat to admire the memorial from the water. “There’s room for more windows,” the captain joked, as the boat slowed in front of the structure, “in case we want to burn any more witches.” A seal popped up to eye us curiously and, as the boat lurched in the swell, Zumthor nodded his head at his creation. “It’s quite good”, he said, breaking out of his reverie, “or as they say back home: I’ve seen worse buildings.” |

Words Christopher Turner

Image: Andrew Meredith |

|

|

||