Realising The Twist wasn’t always straightforward – but now it’s built, the space makes for an ethereal gallery experience, says Joe Lloyd

Images by Laurian Ghinitoiu

There is something of the phantasmagorical about the architecture of Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG). Power stations that blow out smoke rings and have ski slopes, pavilions that coil out of the ground, Lego museums compacted from stepped building blocks: BIG’s projects can seem as if drawn quivering from the realm of dream then cajoled into sturdy physical existence. With The Twist – the practice’s new art gallery in rural Norway – it has created a building so effulgent that, on first sighting, you might wonder if you are still in deep sleep.

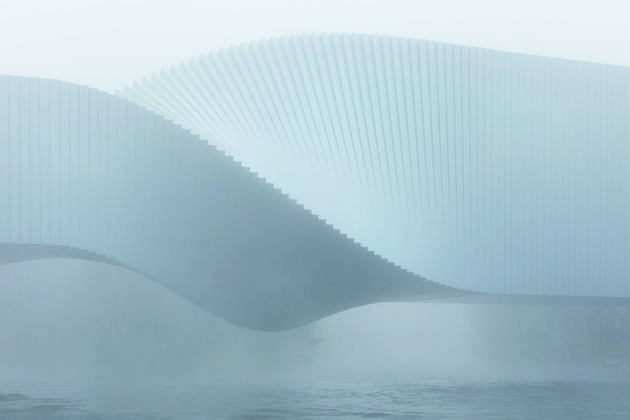

The Twist is an addition to the Kistefos Sculpture Park, 50km north of Oslo, and its first interior space devoted to exhibiting art. It is a twisted shape that takes the form of a bridge. Clad in smooth raw aluminium, its two land-based sides are connected by a central section above the Randselva River that curves around 90 degrees, turning wall into roof and roof into wall. But its structural prowess does not solely account for the sense of wonder it instils. ‘From certain angles, it has this perfect enigmatic form,’ says Ingels, ‘especially when you sit on the west side and perceive the purity. It feels like a giant has left it on the river.’ Luminescent at midday, at sunset it looks hyperreal, beamed down from a different dimension.

The interior is almost as striking, ensconcing visitors in rustic Douglas fir. The tall, windowless walls of the south side warp so that at the light-filled, glass-clad north end, one becomes the ceiling and the other becomes the floor. A sloping path gently guides you through the curving mid-section. Here, more than from the shining exterior, you can perceive the building’s wittiest turn: The Twist isn’t a twist at all, with not a single curling or bending part. It is rather concocted from quadrilateral units that each tilt at a slight angle, more akin to the frame-by-frame movement of animation than the continuous movement of life.

The Twist is modest in scale, at 1,000sq m. There is no antechamber. Beyond the gallery itself, the sole other accessible area is a lower block, which droops beneath the main twist. There can be few lavatorial lobbies as idyllic as this, with floor-to-ceiling windows opening out onto the belly of the building and the river below, which on my visit glimmered with refracted sunlight. A silvery sculpture of a topless man by Elmgreen & Dragset peers in, placing the viewer on display. In the cubicles themselves, the multimedia artist Tony Oursler has projected prying eyeballs on orbs above the urinals.

As Ingels tells it, the inception of The Twist was near-Damascene. ‘We started walking through the park, and as we walked away we found ourselves closer to the water, and then we were wading through the water. Then we realised: it had to be a bridge.’ Project architect and long-standing BIG partner David Zahle gives a more mundane explanation for the form: to fix Kistefos’s circulation. ‘The sculpture park didn’t really function,’ he says. ‘It had a lot of dead-ends. Every time you walked you had to turn around and walk back the same way, which isn’t how a normal museum functions.’ By connecting the two sides of the river, The Twist turns a branching landscape into a loop.

Kistefos is the fiefdom of the Norwegian businessman Christen Sveaas. It centres around the source of his family’s wealth, a wood pulp mill established in 1889 by his grandfather, Anders Sveeas. As a young man, Christen Sveeas rankled at the decision to sell the mill and land to another company. He became a venture capitalist and bought the entirety back. In 1999 he reopened the mill as an industrial museum, which he surrounded with a sculpture park. Extended since, the site now spans 270,000sq m, and is dotted with specially commissioned works by a string of internationally acclaimed artists.

Ingels won the project in a second 2011 competition. Sveaas planned to award the project to Snøhetta, Norway’s most prominent contemporary architecture firm. A Danish member of his board, however, convinced him to give BIG – then a mid-sized firm with a string of projects in Denmark and several competition wins, rather than today’s international colossus – a chance. They succeeded. But Norway was in the throes of the global recession and the project was put on hold until 2015. ‘The appetite for building museums-as-bridges was paused for a little while,’ jokes Ingels.

When it resumed, there were disputes as to whether The Twist was too ambitious, and whether it was possible within the budget. The original plan for a multi-storey museum was shaved down to a single-level kunsthalle, with amenities like a reception and a cafe shorn off. Renders of earlier plants show a very different structure, with the twisting section made from a continuous metal sheet rather than a series of frames. ‘There have been an incredible number of moments,’ recounts Ingels, ‘when I started fearing for the fate and the future of the project. To Christen’s credit, he ended up making the more brave, more daring, more right decision.’

Ingels sees The Twist in the lineage of the covered bridge, stretching back at least as far as Florence’s Ponte Vecchio, though while that bridge in effect serves as a street suspended above the Arno, the BIG project is a single unified structure. It might be better compared to the river-spanning Château de Chenonceau in the Loire Valley. A more recent, more theoretical precedent comes from fellow Danish architect Jørn Utzon’s notion of additive architecture. ‘Utzon had this idea that he could create any imaginable form of mass-produced elements just by repositioning them,’ explains Ingels. ‘I think in The Twist there is this Utzonian commitment to trying to find the simplest, most straightforward way of generating great complexity.’

However straightforward its form, The Twist was not an easy structure to build. BIG was unable to find a contractor in Norway willing to take it on, and had to go with a Danish company instead. Though BIG has designed other spiralling buildings – the 59-floor Vancouver House, Canada, completed earlier this year – The Twist’s orientation proved particularly difficult. ’As soon as you start constructing vertically,’ says Zahle, ‘you can add floorplans. But you can’t add floorplans when you build horizontally.’

As impressive as The Twist is from an architectural perspective, its mettle as an exhibition hall is yet to be truly tested. The inaugural exhibition pairs Howard Hodgkin and Martin Creed, two British artists from different generations working in vastly divergent media who nevertheless shared a mutual admiration. While the performance and video-based works by Creed lose nothing from BIG’s obtuse shape – indeed, a piece that sees three performers walk backwards through the structure shouting becomes even more absurd when glimpsed through the twisting centrepiece – a couple of Hodgkin’s minute paintings hang off the wall with a diagonal tilt, a hugely unconventional arrangement that might belie the artist’s intentions. With larger canvases, there may be further problems. But faced with The Twist’s architectural deftness, it seems churlish to quibble.

The original version of this article appeared in Icon 198, the December 2019 issue. Find out more about the issue here