|

|

||

|

Punk was not invented on the King’s Road. Its true significance is as part of the wider 20th-century artistic avant-garde – which continues to shape music, architecture and design to this day Supported by the mayor of London and the Heritage Lottery Fund, the website punk.london pulls together various sanctioned events taking place in London this year to celebrate the 40th anniversary of punk, which officially began in 1976. The date is not entirely arbitrary: Anarchy in the UK by the Sex Pistols was released, as well as New Rose by the Damned. The Clash, the Buzzcocks, the Slits, the Jam – all formed that year. It’s a reasonable year zero upon which to hang a series of events, most of which were displays of photographs. Pictures of famous punks. Pictures of unknown punks. Safety pins. Sneers. Mohicans. The whole concept is, of course, ridiculous. Joe Corré, the son of Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren, the fashionistas and self-styled leaders of the London branch of punk, plans to burn £5m worth of memorabilia in Camden market on the anniversary of the release of Anarchy in the UK. It is a protest at the appropriation of the movement by the heritage industry. ‘Rather than a movement for change, punk has become like a fucking museum piece or a tribute act,’ says Corré. But this isn’t the real reason the concept is problematic. Indeed, if we believe McLaren, punk was essentially a shallow movement. Its purpose was to grab headlines in order to shift as many T-shirts as possible. If the bondage trousers sold in his shop Sex on the King’s Road were key to punk, surely it is unsurprising that the movement has been recommodified by museums.

Blondie at the Griffith Park Observatory in Los Angeles, California (1977) The main reason why punk.london is pernicious is because, as vital as the first Sex Pistols album was, punk was not born in London. It was born simultaneously in a number of places, and if we look at those places, we get a better idea of how the movement relates to other art forms, and thus of its true significance. One of McLaren’s greatest tricks was to convince the world that the brief flare of punk was a year zero, and that looking at its origins or successors is antithetical to its spirit. Yet punk happened in reaction and relation to other movements in art, design and architecture. In his book No Wave: Post-Punk, Underground, New York, 1976–1980, Thurston Moore, one of the key figures of New York’s alternative music scene, writes: ‘The genuine tradition of New York bands was art rock, with punk being merely just one of its aspects. In a certain light, even the Ramones, who presented such a complete, high-concept package, could be viewed and surely were by the boho brain trust, as some kind of performance-art piece.’ Indeed, the 1970s New York art scene gave punk its impetus: an impoverished city with loads of cheap space suddenly appreciating its position between the early 20th-century European avant-garde and the frustrated potentials of the American continent beyond.

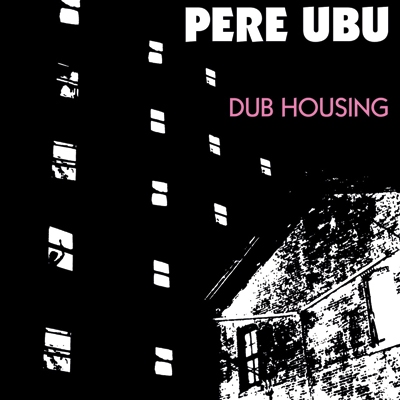

Dub Housing (1978) by Pere Ubu, designed by John Thompson We still tend to see the Ramones as a template of what punk music was – four blokes with guitars, bass and drums – and anything outside this template as somehow ‘post-punk’, yet this is anachronistic. Suicide, a collaboration between artist Alan Vega and musician Marty Rev, began in 1975 as an avant-garde noise project. For Vega, it was a conscious decision to bring to popular music that peculiar hunger for new forms of expression that typified the artistic avant-garde. ‘Art was one thing after another, revolution after revolution, Jackson Pollock, Ad Reinhardt, you go down the line to the Warhol thing, that whole scene,’ he says. Vega believed he was doing the same with noise. Channelling not just Elvis and Iggy Pop but the dadaists, he harangued his crowd over catatonic synth and drum-machine loops. Everyone hated them, including the other punk bands, ‘which made us the most punk rock band of all’, Vega says. The scene in New York coalesced in opposition to them, giving figures like Debbie Harry and David Byrne licence to pursue ever-widening gyres of artistic influence and stirring the appetites of younger musicians such as Thurston Moore and Lydia Lunch to newer and more urgent forms of expression. If New York showed how punk revisited artistic avant-gardes by other means, other US cities showed that punk was a suitable vehicle for understanding and expressing the conditions of modernity. Today, Cleveland and its sister city Akron in Ohio seem unlikely places to consider as the birthplace of punk but, like the industrial cities of the UK such as Manchester, Sheffield and Leeds, these twin hubs of the USA’s steel production fell into decline after the oil crisis in the mid-1970s.

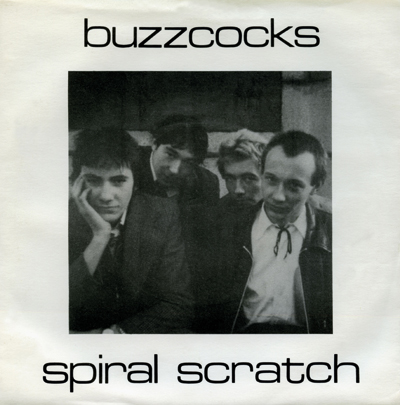

The Russell Club in Hulme, Manchester, 1979. The venue was also known as The Factory on club nights run by Factory Records’ Tony Wilson and Alan Erasmus The band Pere Ubu, named after the hero of a proto-dadaist play, rehearsed amid the mills, carried forward by love of dadaism and experimentations with a dial-operated EML 200 synth. In his book Rip It Up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978–1984, Simon Reynolds describes how Pere Ubu vocalist David Thomas saw his band as very different to UK punks. According to Thomas, the British scene was dominated by fashion, whereas he saw punk as something purely about music and artistic experimentation. ‘Our ambitions were to move it forward into ever more expressive fields and create something worthy of Faulkner and Melville,’ he says. The title of Pere Ubu’s second album Dub Housing refers to rows of public housing, which to the band were reminiscent of the reverberations that characterise dub music. They returned to core principles of modernism and re-engaged with them. In 1976, the year after the band formed, Brent C Brolin published The Failure of Modern Architecture, in which he stated: ‘The human factor was noticeably missing from their architectural equation … it was felt that the uniformity and anonymity of early modernism had been the cause of its social failure.’ Yet Pere Ubu asserted that there was nothing inhumane about this uniformity or even about the anonymity that the city provided. Wire’s rules of negative self-definition 1. no solos The oil crisis brought to an end post-war reconstruction and marked a fault line in the modernist movement, attacking assumptions about increasing mobility and ever-expanding urban forms. Yet young American artists went back to the source material to help them deal with the collapse. Certainly, for art-rock pranksters Devo across the river in Akron, the answer to this crisis was, very distinctively and deliberately, more modernism, questioning it both in terms of visual display and in the relationship between art and society. Similar concerns characterised a number of British bands, despite Thomas’s reservations. When the Buzzcocks released the Spiral Scratch EP on their own label, it galvanised independent artistic production. These small labels, the most famous of which was Factory, were characterised not by a rejection of the music industry but by a desire for aesthetic autonomy within it, providing a model adopted by design agencies and architectural practices from that time to this.

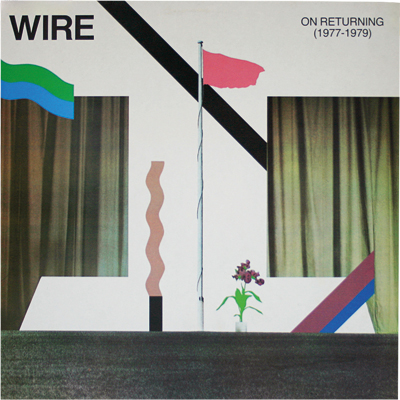

On Returning (1989) by Wire, designed by Bruce Gilbert

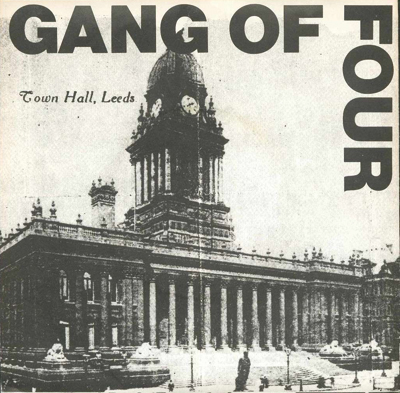

Outside the Trains Don’t Run on Time (1980) by Gang of Four

Noise Annoys (1978) by the Buzzcocks, designed by Malcolm Garrett

Spiral Scratch (1977) by the Buzzcocks The band Wire, formed in 1976, drew up a list of rules that actually included the exhortation ‘no decoration’, as if rhythmic angular guitar riffs and tight baselines were the structures of songs that had to be respected as much as a modernist architect might respect concrete and steel. In his book Totally Wired, Reynolds interviews Andy Gill of Gang of Four, asking him at one point whether post-punk represented a golden age of ‘modernist non-traditional approaches’ to playing the guitar. ‘It certainly felt that people were turning down a new road,’ says Gill, but often they were guided to it, or even forcibly attached to it, by designers. Malcolm Garrett, Peter Saville and Keith Breeden all went to school together in relatively plush Altrincham in Cheshire. Together they connected with international design history by cribbing from Garrett’s copy of Herbert Spencer’s Pioneers of Modern Typography. Saville was particularly taken by the work of Jan Tschichold. ‘I found a parallel in it for the new wave that was evolving out of punk,’ Saville told Rick Poyner in Eye in 1995. Sometimes the bands were more receptive. Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark were arch-modernists, writers of paeans to technology very much in the Kraftwerk vein. Saville worked with them closely, and the die-cut covers for their first album made a graphic pattern of the notation system for synths and drums that the band used. Walter Gropius wrote of ‘freeing the machine from its lack of creative spirit and in the process making the useless useful’ – a sentiment that defines both Saville and OMD’s work in the early 1980s.

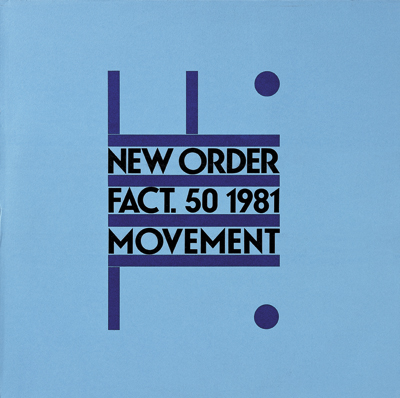

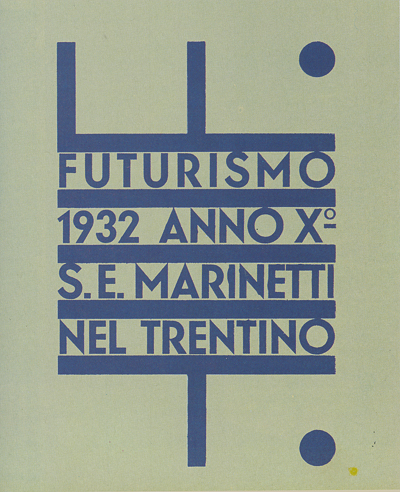

Movement (1981) by New Order, designed by Peter Saville, after Fortunato Depero

Futurismo 1932 Anno X, S.E. Marinetti nel Trentino, designed by Fortunato Depero (1932) These designers effectively lifted musicians from their brutalised immediate environment, relating their work to something bigger. Saville’s covers for New Order took the band’s fascination with the extremes of 20th-century history and located it within the history of artistic avant-gardes, making the apparently unlikely success of a group from an area decimated first by industry and then by its demise seem somehow inevitable. In retrospect, the King’s Road scene looks hideously parochial by comparison. Of course, one could say that such appropriation contributed to major issues that are playing out in culture today. In his interview with Poyner, Saville also says: ‘To me, it was better to quote futurism verbatim, for example, than to parody it ineptly.’ The content may have been modernist in appearance, but looked at one way, this strategy of quotation was postmodernist. Looked at another, the rapid process by which 20th-century art went through a series of revolutions, all under the umbrella of modernism, may have been exhausted, but it was finally moving from the artistic avant-garde into pop music. It has been suggested that contemporary media culture has provided an eternal historic ‘now’, with everything from any historic moment immediately within reach on the internet. That the internet has provided us with instant access to a whole range of information is true, but that is no bad thing. Similarly, it has also given us a new ability to relate to those who share our own artistic interests. How we do this and to what end is more important, and more vital, than pinning punks to a wall or setting fire to pairs of 40-year-old bondage trousers in Camden market. This article first appeared in Icon 157 – read more about it here |

Words Tim Abrahams

Above: The Pruitt-Igoe housing project (1954–56), St Louis, by Minoru Yamasaki

Images: Kevin Cummins; Michael Ochs Archives/Stringer; Bettmann; Movement, New Order, Factory Album 1981, Design Peter Saville, after Fortunato Depero |

|

|

||