|

|

||

|

Amid the noise and rubble of London’s biggest development site, Ooze Architects and artist Marjetica Potrc have created a place where city dwellers can shake off the dust and swim with nature. Welcome to King’s Cross Pond Club After months of anticipation, a striking new outdoor swimming pool has popped up among the brick warehouses, cranes and rubble of King’s Cross, London. This innovative project by Ooze Architects and Marjetica Potrc is now open to visitors, and the first swimmers, submerged in a 40m x 10m pond of naturally filtered water, will get a view like no other, encompassing the half-finished blocks of housing and offices that are rapidly taking shape around the capital’s biggest building site. Ooze’s Eva Pfannes and Sylvain Hartenberg say their public art project – Of Soil and Water: King’s Cross Pond Club – is a chance for urbanites to get reacquainted with nature’s processes. The idea is popular in Germany and Austria; does it have the potential to catch on in the UK? ICON: The King’s Cross Pond Club is the last commission by Relay, whose installations have eased the pain of the area’s constant disruption over the last three years. How did you first Eva Pfannes: We were asked to come up with several ideas for the site, and then decide, together with the client Argent and their partners, which of these would be most desirable – it turned out to be the pond. ICON: It’s quite an unusual proposal; did they take a lot of convincing? Sylvain Hartenberg: They were very excited by this option from the start, as it complemented their amibition of bringing people to the north of the King’s Cross site, where the Lewis Cubitt Park is opening this year. EP: We took pleasure in the proximity of the Regent’s Canal, but also in the proximity of the building site. We wanted to make a project that creates a sort of enclave, a different type of space within the site. When you swim, you are exposing yourself, and the contrast of this experience of exposure with the very noisy and rough surroundings is a strong one.

The pool is at the heart of the King’s Cross regeneration area ICON: What experience will people have? SH: Basically it’s about engaging with nature in a different way. When you swim you’re weightless, you feel lighter. When you come into the enclosure you’re part of this “club” and, because it’s a chemical-free pool that works with plant and natural filters, you have to follow certain rules to respect nature. We are aiming for a combination of intellectual awareness and sensual experience. EP: Sustainability is something quite abstract; we humans often don’t know how to relate to it personally. So this is a general ambition across our projects. We want to make it possible to experience the cycles and ecosystems in nature – to become part of them, on a one-to-one level. The point is to form an association with nature, but also to be reminded that this is not a relationship without limits. SH: If you think about the concept of the Anthropocene, it relates to the fact that we, as human beings, are able to make or break our environment. We have to relearn how to actually work together with nature. That is why as a practice we pursue projects that could be depicted as engineering nature: we want to reveal how to benefit from nature’s processes while also acknowledging the need to adjust and make concessions towards those processes. EP: The French landscape architect Gilles Clément was a strong influence in this regard – in particular his Derborence Island project in Lille’s Parc Henri Matisse. This encapsulates Clément’s concept of the “third landscape”, of spaces that are somehow beyond human intervention. His “island”, in this case, refers to a large concrete outcrop within the park, inaccessible to visitors, the top plateau of which acts as a refuge for biodiversity, thus creating a natural enclave within an urban context that is nonetheless able to achieve its own balance. SH: We saw an instant corollary between Clément and the King’s Cross site through the presence of the adjacent Camley Street Natural Park at the latter. Camley Street was still a coal drop at the beginning of the 1970s, but was abandoned and has since morphed into a wonderful natural resource. Clément’s island had a similar ethos in terms of the idea of nature being left to its own devices and finding its own rhythm, and identifying what benefit that could provide to a city’s population.

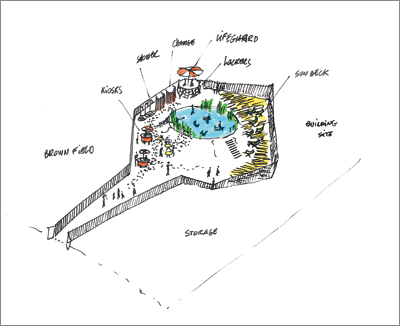

An early drawing of the proposed project, with a small pool and sun deck ICON: So, how does the King’s Cross pond work without chemicals? SH: There are three zones: a swimming zone, a regeneration zone and a filter zone, each with different types of plants. The underwater plants control the nutrients, and create plasma to re-oxygenate the water. The filter plants in the gravel beds release oxygen from their roots that attracts a kind of bacteria that breaks down pollutants, and eats other bacteria. And then you have other types of filtration, like surface skimmers, which remove impurities floating on the water, and phosphate absorbers. There are two sets of pumps running the water and replacing it about every 48 hours. EP: The water is recycled; only the water that evaporates is replaced by the mains. Also, human skin brings a certain load of nutrients into the pond, which the plants like to absorb. SH: While there are no restrictions on who can go there, it’s more about the number who can swim per day. The system is quite fragile and needs time to regenerate. EP: It’s about balance, which is why the number who can use the pond each day is limited to precisely 163. The operator runs it like an open-air swimming pool, with monitored sessions. That’s really how the idea of a “club” came about. It’s not exclusive – we formed a club with nature, and there are some rules of engagement, like any social community.

Filter plants release oxygen to help break down pollutants ICON: Public art is evolving to become more surprising and participatory. Would you say this is a piece of art, or urban placemaking? SH: It’s very layered. For us, it’s important that our projects are like this. You have swimmers, gardeners, you have art, you have placemaking. It’s very important that it’s a complete project that addresses a lot of different issues, that it doesn’t exclude anything by saying: “Oh it’s architecture, or it’s art or landscape.” That kind of classification is from the last century. We live in a hybrid world and a complex society. And that’s exactly what this project is about:

The pool has been given a deliberately industrial feel ICON: Urban swimming is having a bit of a moment, with Studio Octopi’s proposed Thames Baths Lido also gaining a following. Where does your project fit? And why do you think people are now finding the idea desirable? EP: That [Thames Baths] project talks about the quality of water and how water could be cleaned, and the fact that no one has swum in the Thames for such a long time. That’s clearly to do with the fact that it’s polluted. Our project relates to the discussion about natural processes that can clean water. Once you get in the water, you will see how much fun it is; how different it is from a chlorinated pool. The King’s Cross pool is very small, but will begin a conversation about how the Thames can eventually be made cleaner. SH: This project is the first of its kind – a pioneer. It’s going in the middle of a building site, and a building site is where you create a city. We hope that the King’s Cross Pond Club will open a lot of gates for natural swimming to become standard practice. Because of its temporary nature and location, we were able to convince the planners they could take the risk here, just to test how it could function. In London, you already have a culture of swimming in natural ponds – the Serpentine and Hampstead Heath. But it’s something specific: not everyone does it. EP: People told us you can’t see your arms when you swim at the Hampstead ponds. This system could be put in place to make them clean again. SH: The mains water we’re using is quite phosphorous. It took a few weeks of filtering to get it clear and suitable for swimming. The difference that the process made was incredible. It’s like swimming in a mountain lake now.

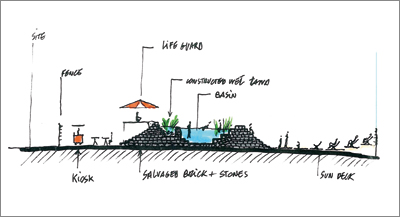

An early drawing showing the pond’s banks built up from waste materials ICON: There’s a lot of frustration in London about the amount of unusable land locked away for development in private hands. This feels like a little victory for the public, albeit temporary. EP: There’s a real desire for people to engage with the project. A month ago, we had a public day where the local community planted 80 different wild species on the site together. One woman arrived too late but still wanted to do something, so asked to at least water the plants. I think that’s symptomatic of people who want to engage and do something for the place where they live. It’s a chance for change. ICON: Does a pond like this exist anywhere else in the world? SH: In Austria and Germany it’s quite standard. The culture of natural swimming, and the technology for it, are quite strong. But now it’s spreading further afield. EP: As is people’s acceptance of the idea. There were some blog comments when this project was published saying: “Yuck! How can you swim in that water?!” People don’t always feel that a pond can be as good as a chemical pool. But if you just go and try it, learning to trust nature and its process of purification, you’ll see.

An outdoor shower on the edge of the site ICON: The pond has a deliberately industrial feel, with red and white wire fences and changing rooms made from construction materials. Its incompleteness makes it look like it was discovered on the site, or popped up overnight rather than being designed. That’s also down to your wild planting, I suppose. EP: What’s exciting about these projects is that they change a lot – you come back two weeks later and everything has grown. The plants in the water also need to grow so, right now, it’s ready but it’s not final. SH: And it will never be “ready” because it’s always evolving. EP: And that’s part of the experiment with wild plants. Working out which ones will grow here, which ones will need to be moved. It’s due to be in place until the end of 2016, and after that, who knows? This article first appeared in Icon 145: Leisure. Read more and subscribe here |

Words Riya Patel

Images: Ooze Architects/John Sturrock; Rob Greig/REX |

|

|

||