|

Jacques Herzog says architectural exhibitions are “an impossibility”, but doesn’t see that as a reason not to try. He talks to Icon about this year’s Swiss Pavilion – which displays the work of his former teacher Lucius Burckhardt alongside models and drawings by Cedric Price – and the prospect of one day curating his own Biennale This article was first published in Icon’s August 2014 issue: Venice Biennale, under the headline “The reluctant exhibitionist”. Buy old issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this The Swiss exhibition, A Stroll Through a Fun Palace, presents drawings and photographs from the archives of Cedric Price (1934-2003), the English architect best known for his “laboratory of fun”, and the Swiss urbanist and landscape architect Lucius Burckhardt (1925-2003), the inventor of strollology, “the science of strolling”. The curator Hans Ulrich Obrist invited Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, who were students of Burckhardt, to co-curate that When they visited Burckhardt’s archive in Basel, they were immediately impressed when it was wheeled out for them to view on trolleys, and that is how they chose to present the work. Actors, coached by Tino Sehgal, an artist who creates “constructed situations”, roll out boxes of material and engage visitors in engaged discussions about Price and Burckhardt’s work. Here, Herzog explains why Burckhardt, who pioneered the inter-disciplinary analysis of man-made environments, and emphasised both the visible and invisible aspects of place-making, should be better known outside Switzerland. ICON: The Swiss Pavilion is devoted to a creative collision between the work of Lucius Burckhardt and Cedric Price, who as far as I know never met. Price’s architectural ideas are familiar to a British audience, but who was your former teacher and why is he important? JACQUES HERZOG: Both Pierre and I were taught by Lucius for two years at ETH in the early 70s. We were certainly influenced by him, sharing many train rides between Basel and the university in Zurich, because we were all based in Basel. He was not only a teacher but became a great friend, even if he represented thinking that was, as we found, against architecture as ICON: What did you learn from him? What does the juxtaposition with Price yield? JH: The influence was not concrete. A teacher is always someone who inspires, fascinates you, rather than gives concrete recipes. The greatest thing we took from him was really this conceptual and critical thinking, debating and discussing things, rather than thinking of the architect as the great master who performs a stroke of genius and then that’s it. That has never been our method because we have been a couple, always. We have a collaborative approach, and the talking, and the thinking, and the laying out, exposing, is something we cannot avoid and miss. Lucius and Cedric Price were totally different people – I don’t think they knew each other. But it was Hans Ulrich who had this idea to bring them together. Because in some ways, in both of their work, you see the doubts, the hesitation, the critical distance to the official production of architecture. And then I think the means of drawing, the ways the drawings help and express the thinking, is quite interesting to compare.

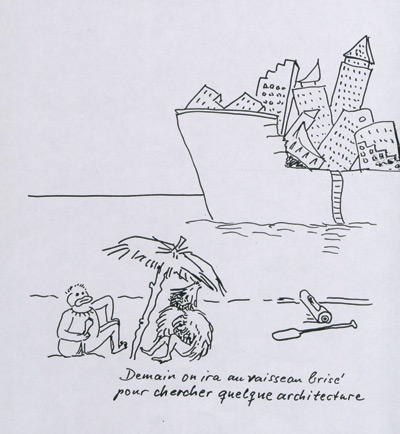

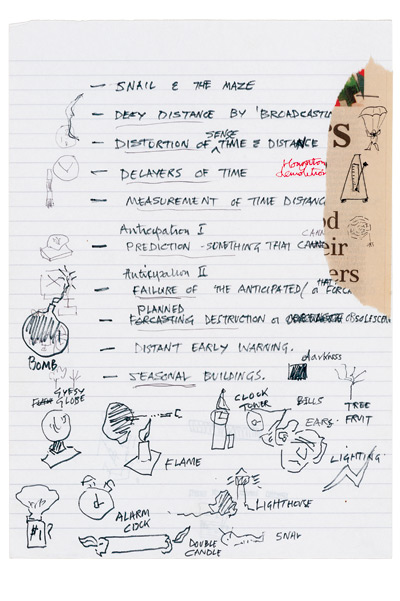

Drawing by Lucius Burckhardt ICON: Price did some beautiful drawings of his eccentric plans for Battersea Power Station [Icon 130]. You obviously adapted Gilbert Scott’s other power station in London, transforming it into Tate Modern. Has Price ever been an influence on you? JH: Not for that particular project. Cedric Price is a kind of hero in the Anglo-Saxon world, but we’ve never really been under that influence – much more with Lucius. The Fun Palace is of course an interesting concept, for an architecture that was a precursor to the Pompidou. But we learned more about Price through this particular show than ever before. ICON: Burckhardt was a great activist, always keen to get the public to participate in the discussion of what a particular building might be. Has that explicitly political element of his work been an influence on you? JH: Activism was very important in the 1970s, because planners weren’t always accommodating to those people who had other needs of public space. But what I somehow find fascinating, and sometimes also very painful, is, of course, his loneliness. He was always against something, against planning, against too fast decisions. It was always the last thing you should do, to physically add something to the world. That’s theoretically very interesting, and as I’ve said before, that remains very important – why would you want to introduce a piece of architecture? His work expressed almost a rejection of intervention, and certainly we’re not on this side, but we very much stress this moment of waiting, and thinking in concepts rather than making fast decisions. ICON: Why did Burckhardt not accept, as you have said, “architecture as architecture”? JH: He rejected the notion of the typology, and the architect as a genius who can amalgamate everything in his own thinking, and then come up with a finished product that is to take or to leave. Whereas architecture very often is like that, ideally it fulfils a programme, and adds beauty to a place. The Swiss Pavilion is a good example. That was not the result of a participatory process, but for him, architecture always had to be the result of a public process, and I have serious doubts about that. When he saw a plan by a student, and it did not look like one of his typologies – which represented the idea of the permanence of the city, of the monument – he was disgusted. I couldn’t think of two people more different; but both were communists, opposed to the status quo. Lucius saw architecture as the means of transformation, and so did Rossi, because he saw going back to the classical typologies as a way of fighting the erosion in modernism. Lucius saw it the other way around; he saw modernism as a danger because it was just speeding up what had been wrong before, in history. It’s very interesting to look behind that thinking and reveal the crisis of architecture that lasts until today, which is the theme of this Biennale. ICON: For the Swiss exhibit, you spent time in Basel sorting through boxes of Burckhardt’s archive. What discoveries did you make? JH: There was so much stuff that we were almost a bit blind. We didn’t want to sort out and build categories into which his work would perfectly fit: politics, activism, real projects, drawings etc. But how could you categorise him? That’s why we came up with the concept that’s more like a theatre, which I think is right for Burckhardt and for Price. Rather than presenting the work in neat frames or drawers, it’s a lively presentation – young people bring up material in archive boxes, and wheel it in on trolleys, striking up conversations with visitors about the work. ICON: In the last Biennale you devoted a large space to a frank presentation of all the negative press given to your Elbphilharmonie project in Hamburg. Why did you choose to do that, and what’s the status of that building? JH: I think that was a bit misunderstood. We really wanted to show the project and we couldn’t ignore the controversy that came with it. We did not want to provide our own commentary because it would be seen as too positively interpreting our role, or the role of architects. So we decided to show literally everything: the good, the bad, the stupid, the ugly. At the same time, in the accompanying displays, we wanted to show the beauty of the many things that are in this project. To say, ultimately, this is what we’re after. To reach that, however, is somehow an unlikely case. Because the triangle between the politicians – in this case the client, the city of Hamburg – the construction company and the architects is so complex and so difficult in a democracy. And that is something we want to expose and debate. The exhibition was a first step to something we’d like to put into the foreground, so as to give a voice to all these different forces, because somehow we cannot avoid dealing with it. Now there are new contracts, which clarify the role of each partner, so we’re in a good place. And the project continues – the opening date is, I

Drawing by Cedric Price ICON: What do you think of Rem Koolhaas’s Biennale? JH: I think it’s another attempt to see whether you can expose architecture, which is also an unlikely intention, because it’s not possible. But I think Rem makes a big step into another conceptual approach – it’s certainly interesting to discuss that and try something totally different. We’ve done our own exhibitions, in the Pompidou and the Tate; always tests on how you can show architecture. Because architecture’s made to be shown somewhere, and that’s very different from an art exhibition. I thought, on first visit, that one of the best parts of Elements was the art part, Wolfgang Tillmans’ film, because it’s an artwork, it functions in itself, it is what it is. And that’s very telling on the impossibility of doing an architectural exhibition. ICON: Would you like to curate a Biennale in the future? JH: We have been asked, and I was not ready and willing. I’m still undecided, because of what I just said. If I did so, it would be about the impossibility of displaying architecture. Architecture always represents something that is somewhere. But maybe in four years we could. I think you also have to devote a lot of time … I mean, I think Rem is pretty tired! However, the more I speak about it, the more I think I have some ingredients that could work. I haven’t spoken to [Biennale president] Paolo Baratta again but, certainly, I will do that. |

Words Christopher Turner

Images: Cedric Price archive, Centre for Contemporary Architecture, Montreal; Lucius & Annemarie Burckhardt Foundation |

|

|