|

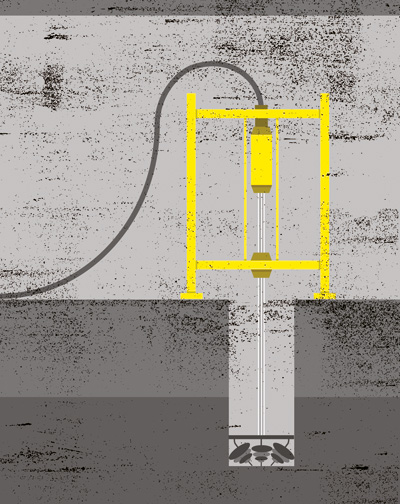

An underground repository where nuclear waste will be buried is under construction in Finland. Liam Young talks to Michael Madsen, who has made a documentary, Into Eternity: A Film For The Future, about the controversial facility and its legacy This article was first published in Icon’s July 2014 issue: Underground, under the headline “Building into eternity”. Buy old issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this LIAM YOUNG Onkalo is a nuclear waste repository 500m deep, hollowed out of solid bedrock in Finland, designed to last for 100,000 years, the length of time the material inside remains dangerous. It is a building that never dies, a structure that will outlast civilisation. The underground has always been a setting for sci fi apocalypse, most often as the site of refuge and retreat. We descend to escape a surface we have destroyed, or to seek shelter in bunkers, waiting for the end of the world. What do we do when the underground is no longer safe, but the source of contamination? MICHAEL MADSEN It takes 30 minutes by car to descend the spiralling tunnel of Onkalo. It feels like a space that human beings aren’t meant to be in. I could sense the weight of all the bedrock above, it was like being submerged in water. It is as if you are descending into some kind of underworld, but strangely it is also a site of the future. The impetus for Into Eternity was that I have no conceptual understanding of what 100,000 years even means but that there must be some architects and engineers entrusted to work on this project that do. What would be their metrics to determine whether this would be the right way of going about the building? In answering these questions about what the distant future might mean, I thought that at some level this facility would tell me something urgent and critical about the civilisation that we live in. What concerns the project’s safety experts is that across the waste materials’ lifespan the dangers of this facility are easily forgotten and human curiosity might lead people to go down there. That was when I realised that the real threat to this facility is not groundwater seeping in, but it is something within ourselves, our inquisitive nature, perhaps the very thing that led us to discover the power of nuclear energy in the first place. LY You address your film to an audience of the future, but is this an architecture that is more about comforting us in the present? The Global Seed Vault is another site on the edge of our imagination. We know it’s there – as Google explorers we see online images of its grand entrance, poking through a snow-covered hill. It sits, protected below ground, full of plant stock, a biological insurance policy, waiting for the end of the world. Half a world away we sit, reassured that somewhere out there is this ark, travelling with us through time. We know so little about the technologies required to contain the radioactive material bound for Onkalo, but is it actually more a project that allows us to sleep at night, which fills us with the consoling thought that at least we are trying something? MM The construction of Onkalo is very much about evoking the sense that we are now acting responsibly. Nuclear waste is the Achilles’ heel of nuclear power and if you can argue that this issue has been solved then the main opposition to it dissolves. But as you also suggest, Onkalo is a very concrete manifestation of the limits of what we are able to understand. One hundred thousand years ago is probably the time when the first humanoid left Africa, so for us to come to terms with what this means is impossible. Nuclear energy and genetic modification are the first examples of technologies with impacts that stretch into the distant future. We learn as we go along but we don’t comprehend the consequences of our technologies at the same pace as we invent them. It was curious for me to learn that there are no philosophers or thinkers attached to this project. They are all geologists or engineers, but that is only one part of the equation.

LY What might be a potential strategy to engender such long-term thinking? The periphery has always been the place where we put things we don’t want to see. The underground is just an elaborate periphery condition. With my own research studio we go on expeditions each year to visit these hinterlands that the world chooses to forget, such as the oil fields of Alaska, the mines of outback Australia. The technologies of our cities cast shadows that stretch far and wide. Part of the impetus for visiting these sites is to bear witness to them and bring back knowledge of their existence to the cities that have ignored them. Would an awareness of its presence, the impossibility of its grand task, force us to consider the act of bringing into the world radioactive material that needs to be tended for 100,000 years? MM Bearing witness is a very interesting concept. In Into Eternity there is a discussion about landscapes or monuments that would communicate on an intuitive level to people in the future that this is a dangerous place and you shouldn’t be here. The problem with traditional monuments is that you need some kind of context for it to make sense to you. This context cannot be assumed across the time scale of Onkalo. When discussing the possible visibility of the nuclear repository I refer to the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin by Peter Eisenman. It is a monument which is nonfigurative, there is no soldier on horseback immortalised in stone to tell us a story from history. The Holocaust Monument I believe is much more interested in creating a situation, a certain presence on an intuitive level. It is a maze in which you cannot get lost, it is about the density and the gravity of its concrete slabs. It induces in you an alternate state of mind and in this way it is much more interested in the present moment of its occupation than in the historical details of what happened in the Holocaust. I don’t think that the architect of that memorial thinks it is important to bear witness in this case, he is much more interested in someone, born years after the event, having their own personal reaction to the space. LY When our studio travelled to Australia, we spent a lot of time in similar excavations. We found that there was an amazing correlation between those holes and what is going on back in a global city like London. The digital design models of the mine excavations are linked live to the gold price index – you can see the global financial crisis in the same way that you can see the layer of iridium from the meteor that wiped out the dinosaurs. Could we talk about Onkalo as a similar icon of the anthropocene? Is Onkalo the first deliberate anthropocenic design, the first building that is conscious of its own footprint through geological time, where excavators, explosives and diggers have replaced the slow erosion of rivers, wind and rain. Where do you think these marks we are now making on the Earth sit in the lineage of the great pyramids, the sewers or the Panama canal? Is Onkalo a temple or a ruin, a monument or our dirty little secret?

MM Onkalo is perhaps the first purpose-built building expected to outlast civilisation as it is being designed to withstand the pressures of the next ice age. The way you phrase the question makes me think that one way to understand this facility is that it is an architecture that is wiser than its makers. It is a purely functional design, but scrawled across the bedrock is a tracery of numbers and symbols that follow fault lines in the rock, the graffiti calculations of potential water seepage. While I was down there I couldn’t help but wonder whether, if this building was ever opened up, these marks would be the cave painting record of our time. They would be the remains of what would appear a purely scientific and logical civilisation. LY You describe Onkalo as “the place you must always remember to forget”. Like the Voyager probe, endlessly drifting beyond our own reach, I think of Onkalo as a light that we shine into the furthest reaches of the future. It is a message in a mountain, a monument to us. Is it a building of hope or of sorrow? MM As we sit here, Voyager is leaving our solar system – the first manmade object ever to leave. One of the interesting things about Voyager is that the depictions of Earth show only human beings – there are no animals and very little interaction with our surroundings. It seems as if these creatures depicted are somehow not connected to the world that they are sending this craft from. It has been discussed that this in fact might be the downfall of the human race, that we do feel superior in different ways but we are also strangely detached from reality and nature, from living in this world, which is the only one we have. Michael Madsen’s new film The Visit, about alien intelligent life, will have its premiere in autumn 2014 |

Words Liam Young

Illustrations The Lindström Effect |

|

|