|

|

||

|

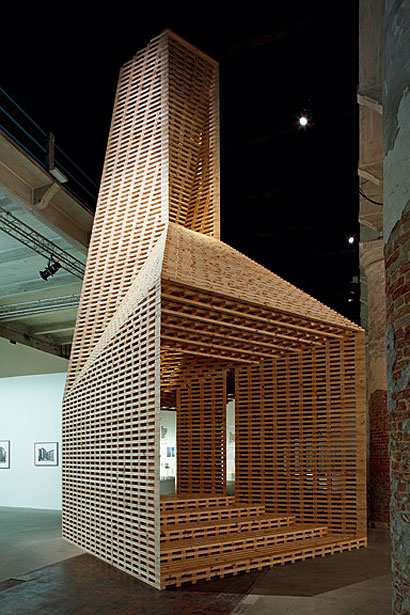

At the heart of the Corderie at the 2012 Venice Architecture Biennale stood Vessel. It was a towering timber structure by O’Donnell + Tuomey, the Dublin-based practice founded in 1988 by Sheila O’Donnell and John Tuomey. The practice juxtaposed the monolith with 1:50 scale models of buildings by the likes of Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto. It was an intelligent exploration of the spatial relationship between interior and exterior extended to a dialogue between each of the architects selected. “We put a lot of ourselves into the Venice exhibition,” Tuomey says. “We decided to make it into a document of our interests in architecture and our life interests or something.” The installation was a snapshot of the way that O’Donnell + Tuomey works; Vessel carried the spirit of the practice’s permanent works and placed them in dialogue with past masters. “We used it as a way to summarise and think about what the work we have done means,” O’Donnell says. “I suppose it is interesting to consciously try to represent the influences and affinities that we have always been working with.”

Earlier in the year, back in the more familiar territory of Belfast, Northern Ireland, the Lyric Theatre on the banks of the river Lagan was completed. They won the competition for the 5,500sq m building in 2003 and it took eight years of briefing, design, fundraising, demolition and construction to complete. For O’Donnell + Tuomey, the struggle was worthwhile.”The actors seem to thrive in it, the audience seem to feel at home in it. That makes me feel very satisfied,” Tuomey says. “It’s a small building, but it seems to have a big impact on the social life of the city.” The Lyric brings together the front and back of house, with every part of the building working as part of the theatre. The brick exterior was assertive and, in referencing the red-brick terraced housing adjacent to it, brought coherence to an awkward site without succumbing to the gimmicks or wilful visual tricks that so often typify modern cultural buildings. Last year was also significant for the practice as it marked a return to London, where O’Donnell and Tuomey had both spent time working for Stirling Wilford before founding their own studio. The Photographers’ Gallery is a refurbishment and extension of a former warehouse building tucked away behind Oxford Street. It is a neat stack of galleries that climbs above the narrow streets of Soho to offer views across the city. This will be swiftly followed by the London School of Economics Students’ Union, a much larger multipurpose building in Holborn due to open later this year. “In both cases we hope that the buildings are wriggling free of their sites to break into the city landscape,” Tuomey says. The LSE building is the most substantial the practice has produced to date, but the change in scale has not diffused the architects’ curiosity in pushing the possibilities of a complex brief and site. “The faceted form came out of the practicality of a right-to-light envelope, and the glimpses you get of the building down the streets,” O’Donnell says. “Then you get a really interesting conversation about how you can push or use the inherent characteristics of brick to make something. It has been really interesting and I hope it will be interesting when it is built.” Across the practice’s built portfolio, it is apparent that O’Donnell + Tuomey is adept at executing the pragmatic concerns of construction while combining them with a wider cultural perspective that draws context, place and ideas together so that the completed buildings are more than simply containers for activity. It is these connections between the mechanics of architectural design and the wider world that drive the concepts behind each building, creating rich experiences that force each element, physical or otherwise, to have a purpose beyond pure function. “I think it is a strange thing that happens to architects, and I don’t mean to be impolite in any way, but sometimes their horizons are a little narrow,” Tuomey says. “Architecture is so complex that it has these other resonances in it,” adds O’Donnell. “It needs ingredients like art, culture and philosophy that act as genuine inspirations.”

This belief that the key to creating meaningful places lies in the affinities between the physical presence of architecture and other less tangible influences stems from their early architectural education in Dublin. “We spent so long in our early life chasing down country lanes trying to find the soul of Irish architecture. It’s just not there,” Tuomey says. “What came out of that was that we learned that it is more interesting to look at things like a discovery, with wonder.” In practical terms, this translates into a design approach that relies heavily on exploration through words and sketches. “We work a lot on paper with sketches and overlays. When you paint and hand draw it slows you down and brings you into a hypnotic relationship with the work. A little bubble,” O’Donnell says. “I don’t want to sound like a stick in the mud,” adds Tuomey. “I don’t think a single thing has changed about the way we work. I come in and sit and draw at my drawing board. We want to stay true to what we wanted to do when we started, maybe that has held us back. I don’t know.” Despite Tuomey’s modesty surrounding this laboured and intense approach to architectural design, it is clear that the effort is worth it. Now, the 15-strong practice is broadening its horizons and preparing the design for its most significant project to date, the Central European University campus in Budapest. “Budapest is our new discovery. The project feels like it came along at just the right time for us,” Tuomey says. The architects have been inspired by the courtyards that abound throughout the city and will be finding a way to weave two new buildings into a network of five 19th-century squares. Like so many of the past projects, it is a careful alignment of old and new with an astute eye for what makes a place special. “There’s no doubt that it starts with the Irish Film Institute,” says O’Donnell, referring to the practice’s first permanent project, completed in 1991 as part of the regeneration of Dublin’s historic Temple Bar district. “It’s the kind of work we really enjoy. It has a mix of old and new. It’s interesting to see how little you need to do to transform old buildings, or if they even need to be transformed in any way, just revealed a little bit. There’s a lot of that kind of thinking.”

|

Image Mike O’Toole; Alice Clancey; Dennis Gilbert; O’Donnell & Tuomey/Millennium Models

Words Owen Pritchard |

|

|

||