|

|

||

|

A city like Los Angeles can nearly disappear beneath its own myth. Deemed a city of “dreadful joy”, of golden dreams, an “autotopia” or a hell, it has provided a malleable stage set, reborn in thousands of scripts. The most popular myths are the sun-kissed rise to fame and its more recent cousin: a gritty chaos, awaiting apocalypse. Neither, though, are quite true. Filmmaker Thom Andersen has declared that Los Angeles was “just beyond the reach of an image”. Seven years ago, he released Los Angeles Plays Itself, a three-hour “city symphony in reverse” that looked at how “the most photographed […] least photogenic city in the world” was portrayed in cinema. Throughout the film, he reveals the layers of cinematic artifice that have calcified over Los Angeles’ bleached grid, and questions whether a city so theatrically mediated could ever really be seen.

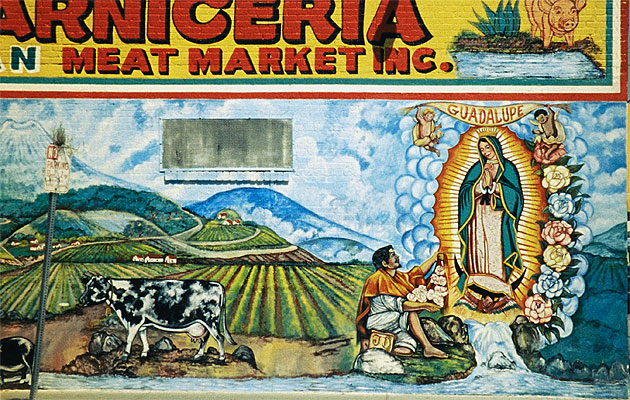

His latest film makes an attempt. Get Out of the Car! pays tribute to the unheroic, the overlooked and the disappeared. It begins with shots of the ruins of advertising: the metal scaffolding of empty hoardings and the unintelligible billboards whose imagery has faded under the perpetual sun. The camera focuses on the texture and surface of Los Angeles’ arid empire of signs, honing in on the variety of abstractions caused by wear and decay. Hand-painted murals receive a similar consideration, from saturated images of the Virgin of Guadalupe on the sides of garages to cartoon characters gracing pale stucco walls. Goofy rooftop sculptures (such as a giant hotdog) signal the city’s anachronistic kitsch. The film’s title demands you get out of your car, yet most of these sites were built specifically for car culture. The billboard evolved with the highway and the first neon sign in the United States glowed from a Los Angeles car dealership in 1923. Advertisements were meant to grab the attention of fast-driving spectators from many miles away and they developed a rich vernacular style. Of course, advertising is as prevalent today in Los Angeles, but now the same repetitive names blandly mark every block. Such prevalence tends to render things invisible, so the title is right: you must get out of the car to really see your city, even if the city was built for your car. Andersen’s desire to reveal another side of Los Angeles extends to its effaced history. During the film, he visits several empty lots that used to be vital centres for particular communities, like the South Central Farm – a large communal garden for the neighbouring Latino population. Here he posts a handmade commemorative sign on the razor wire fence recording the farm’s existence and controversial closure in 2006. In another scene, he holds up a black-and-white photograph of a building against the emptiness that has taken its place. Andersen asserts that his is a “militant nostalgia”, not a passive one. By resurrecting the overlooked, he offers an alternative story of the city he’s lived in for decades, rife with political as well as aesthetic motive. All the illusion and stagecraft has been stripped away, leaving empty lots and bare scaffolding – a city symphony in a minor key. |

Image Get Out of the Car!

Words Lyra Kilston |

|

|

||

|

|

||