|

|

||

|

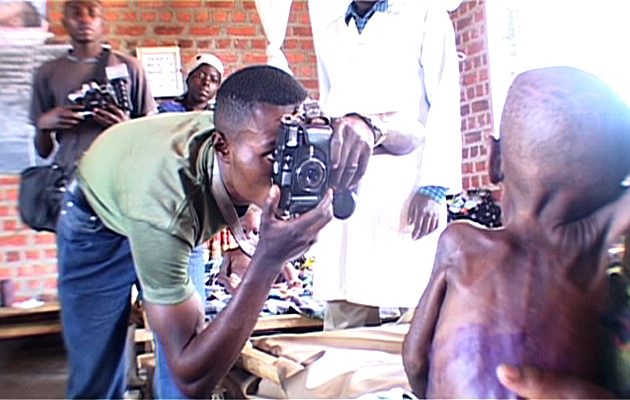

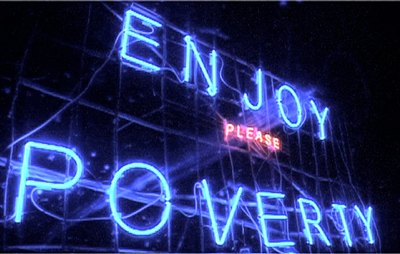

Artist Renzo Martens is attempting to recreate the economic effects of the commercial art market in cities such as London and New York on a plantation in central Africa In 2008, Dutch artist Renzo Martens made a 90-minute film set in the Democratic Republic of Congo called “Enjoy Poverty”, in which he established that pictures of poverty have become a lucrative export and attempted to persuade Congolese photographers to capture images of war and disaster, thereby benefiting from the commodification and fetishisation of their country’s suffering. His most recent work – a series of chocolate sculptures based on self-portraits of Congolese plantation workers – is on display in Cardiff as part of the exhibition of nominees for the UK’s most lucrative contemporary art prize: Artes Mundi, a £40,000 award for an artist who “explores and comments on the human condition”. In the lead-up to the announcement of the winner on Thursday, Icon went to Cardiff to interview the 41-year-old Martens – who lives in Brussels, Amsterdam and Kinshasa – about his controversial approach and watch a group of Dutch pastry chefs melting chocolate to create some of the works on display. ICON: You have two works on display as part of the Artes Mundi exhibition – the film Enjoy Poverty and a set of sculptures. Could you tell me a bit about them and explain how they are connected? RM: I spent four years making Enjoy Poverty in eastern Congo, to try to help poor people understand that poverty is commodified, and therefore it should be them that profit from it. As part of this “emancipation programme”, I had a big neon sculpture made that said “Enjoy poverty”, which I set up in cocoa plantations. But I later recognised that, however critical the film is of labour conditions in Congo, the places where it had a social and economic impact were not there but in New York, Berlin or London – where the film was shown.

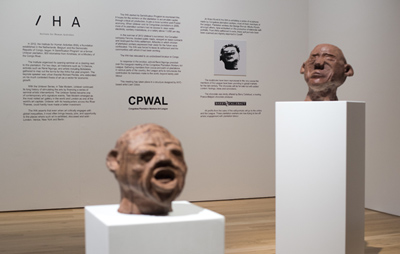

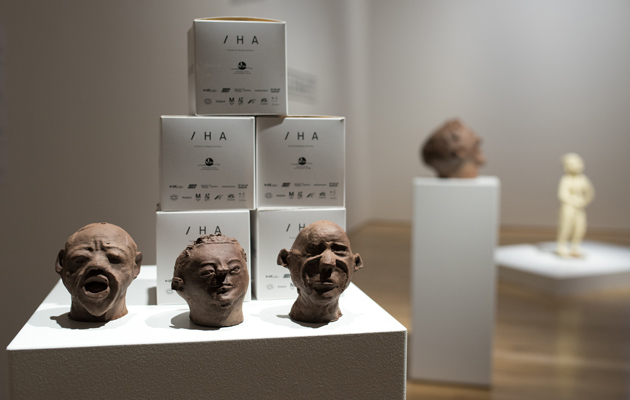

In his 2008 film, Martens sought to help poor people understand that their poverty had been commodified That is the fate of most critically engaged art. Whether it deals with the North Pole or Congo, the places it really has an impact are the gentrified centres of world art: that’s where people discuss it and drink cappuccino, and that’s where it spurs the economy. In response to this problem, I founded the Institute for Human Activities, which is trying to gentrify a plantation in the Congolese rainforest. On Congolese plantations, there is no healthcare to speak of, salaries are under a dollar a day and there’s no sewage system, electricity or clean water. I could make a film about these conditions, but what would happen? It would spur an economy of cappuccino bars and hotels in New York and Berlin. So instead, I have built a critical arts centre on this plantation. At the National Museum Cardiff, you can see a series of self-portraits made by the plantation workers, such as Djongu Bismar and Mbuku Kipala. The idea is that these people can’t live off plantation labour, but maybe they can through the proceeds of critical engagement with plantation labour.

The chocolate scuptures are on show at the National Museum Cardiff They sculptures were made in clay, but we couldn’t transport it to the exhibition, nor could we invite the authors of the pieces from Congo to Britain – they wouldn’t get visas. Instead, we scanned them and then digitally exported and reproduced them in Cardiff in the very chocolate that comes from these plantations – just another chocolate bar from the Congo, but with something added.

The sculptures were recreated by chocolatiers based on the original clay self-portrais by Congolese plantation workers Did you encounter any setbacks when going about your work? One of the plantation owners chased us out at gunpoint a year ago, so we had to relocate. We had established a programme of creative therapy, helping people come to terms with their own lives by making drawings and sculptures about it, but they took away these drawings and told us to never come back. Do you think that many artists engaged in creating “critically engaged” art don’t go far enough in their critique? It’s necessary to critique the system, but your critique doesn’t go far if it doesn’t acknowledge that your position is dependent on the economic status quo. As an artist, you make your work sterile if you don’t acknowledge that it wouldn’t be possible without the existence of global inequalities. That could be considered a cynical position, but it can also be emancipatory, because only by making clear what the suspending apparatus for art is can we formulate work that can tackle this suspending apparatus.

Even the most critical art is funded by the very entities they critique. On a symbolic level, a piece of art may well critique capitalism, exploitation or global inequality, but more often than not, this is used to make western cities attractive for capital and real estate investment. A great example is Tate Modern in London – after Unilever funded its series of art events, the Tate became the most visited art gallery in the world. There are many examples of art being funded to create a favourable business climate and attract high-net-worth individuals. I don’t think we can afford to just be “critical” and leave the real effects of art to be managed by real estate investors and politicians, because they fund galleries and museums in places where they want gentrification to take place. To reverse that, we are copying-and-pasting how capitalism works these days to Congo. We hope this will attract capital and diversify the economy.

Renzo Martens in his 2008 film, Episode 3: Enjoy Poverty Do you think your position of privilege and power in relation to the plantation workers is somewhat problematic? Maybe it is problematic – me, as a white, middle-class, western man, going to the Congo to set up this kind of programme – and yet what I try to do is fully inhabit what I am. It must be clear that white, middle-class, western men are also the ones that get the coltan, diamonds, palm oil and cocoa from such places. It would be strange if we allowed such people to extract resources, while strategies to make these systems visible are off-limits because they are considered racist or problematic. Global inequality, and the role white, middle-class, western men play in it, is terrible. I acknowledge that and I think my work problematises that, while using myself as a stand-in, in the most damning terms possible. Martens’ work is on display at the National Museum of Wales and the Chapter Arts Centre in Cardiff until 22 February. The winner of the Artes Mundi prize, for which eight other artists are nominated, will be announced on Thursday, 22 January |

Words Debika Ray |

|

|

||

|

The chocolate scuptures are for sale in Cardiff |

||