|

|

||

|

Ever since choreographers began to test the conventions of classical ballet, which were codified in the 19th century, they have fallen into two main camps: the ones that start with the music, and the ones that start by testing the body or testing the space. The opposite ends of this spectrum can be represented by Merce Cunningham, whose use of chance operations meant that his dancers sometimes didn’t know what music they were about to dance to (or what costumes they would wear, or even if they would dance at all), and Balanchine, who thought of the music as “a floor for the dancers”. The Belgian choreographer Frédéric Flamand can be placed firmly in the first category. Since 1996, he has collaborated with a number of leading architects – Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio, Zaha Hadid, Jean Nouvel, Thom Mayne, Zaha Hadid and Dominic Perrault and, most recently artist/architect Ai Weiwei. In these works he explores the relationship between bodies and environments, specifically the city, and tests the limits of a more limited, but contested space: the traditional proscenium arch stage. The Marseille ballet, which Flamand has directed since 2005, has its home ten minutes’ walk from the coast in an elegant, curved white building by Roland Simounet. Flamand however trained in experimental theatre and for many years worked in much more unconventional spaces. In 1979 he founded Belgium’s first multimedia centre in a disused four-storey, 4000 sq m factory in Brussels, to which he invited artists as diverse as Robert Wilson, Joy Division and William Burroughs. He speaks enthusiastically of those early days: “That was fantastic: a very organic and transitional space, from one discipline to another.” And it was after the experience of taking his own pieces on tour and rethinking the conditions of performance that, “Slowly I began to be interested in architecture, to question the normal space of the Italian theatre”. (The proscenium arch we are used to, with an arch framing a stage that faces a separately seated audience, was invented to hide the elaborate stage machinery of early Italian opera, and quickly spread to be the norm in both ballet and theatre.) He approached Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio in 1996, prompted, he says, by Diller’s remark, “Architecture is everything that happens between the skin of one person and the skin of another.” Scofidio’s memory of their first encounter is slightly different: that Flamand made contact after seeing a drawing for a theatre piece they’d made about Duchamp. “The drawing was of a figure we called ‘The Juggler of Gravity’. A title very apropos of dancing,” Scofidio says. Moving Target, which was created for Flamand’s old company Charleroi Danses/Plan K (previously the Royal Ballet of Wallonia), is inspired by the diaries Nijinsky began after his last performance and continued in madness until his death. The production’s most striking feature is the placement of what Scofidio calls “an interscenium” – a mirror-cum-projection screen that gives the audience a reflected overview of the dancers. When pre-recorded footage of the dancers is projected on to the screen, Scofidio explains, “the mirror synthesises dancers into video space … Live dancers are freed from the confines of gravity as the mirror re-orients everything by 90 degrees; the pre-recorded dancers are freed from the confines of bodily physics.” For Flamand, this represents not Nijinsky’s experience of schizophrenia and the tragic alienation he came to feel from his body. It also tries to communicate the different roles in which contemporary society casts us: “the real body, the virtual body, the mediatised body, the normal body, the so-called pathological body”.

credit De Cugnac, courtesy of Ballet National de Marseille Breaking down the distinctions between live and recorded performance, to disorient the audience and create new spaces and a sense of time, is a frequent tactic for Flamand, who acknowledges that he continues to work with many of the ideas first floated in Moving Target. Two further works with Diller and Scofidio, EJM1: Man Walking at Ordinary Speed and EJM 2: Inertia, were inspired by the time and motion studies of Eadweard J Muybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey. For both pieces, Scofidio explains, they turned the stage space into “a production studio”. A projection screen as wide as the stage was hung from a gantry and an on-stage operator worked a live camera so that the screen showed both pre-recorded movement and that of the dancers onstage. Then as the screen moved downstage, Scofidio adds, “the dancers are progressively obscured by the screen and replaced by their live and recorded video counterparts. Stage and screen are in fluid exchange.” Flamand stresses that he never thinks of the architects he’s worked with as set designers. “I don’t ask them to make decor! Exactly the opposite: we work on concepts, and ideas come from texts. We work on the theme of the city for example, and I think an architect who builds cities is better than a set designer.”

credit Fondation Le Corbusier In the last decade Flamand has become increasingly interested in the relationship between the body and the city, an interest, which came together with remarkable neatness in his first major work as the director of the Marseille Ballet. Flamand says, “I arrived in Marseille and the only thing I knew about Marseille was the Radiant City by Le Corbusier. So it was really obvious to work on that, but it’s less about the building and more about a reflection of utopia, the utopia of the modernists.” For this project he approached the French architect Dominique Perrault. “Dominique Perrault is not very Corbusian, not at all!” Flamand says, once again, enjoying the joke. However Perrault points out to me later that he’s very keen on geometry and wanted to create “a machine to dance, a machine for choreography, with the proportions, with the geometry, with the restrictions between the components.” So in La Cité Radieuse, Flamand and Perrault took Le Corbusier’s proportional system, the Modulor – the 2m 26cm square based on the area covered by a man with upstretched arm – and wittily reapplied it to the human figure. Perrault created a series of Modulor-sized screens, made of his beloved metallic mesh, (which can be seen everywhere in the shutter and grille systems in the Bibliothèque National in Paris). But here in Marseille, and on stage, the dancers created moveable corridors and cages out of these screens. Once again, images were projected on to these screens. Flamand compares this to “an electronic skin … when you see a city, like Shanghai, or New York or London, you can speak about a sort of electronic skin invading the city more and more.”

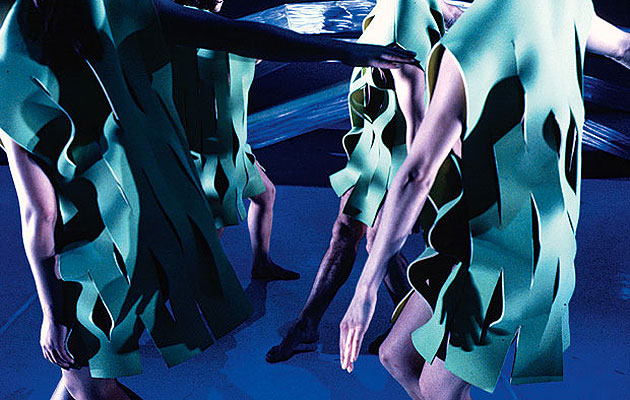

credit Pipitone, courtesy of Ballet National de Marseille Dancers and the details of their movements, can often seem like an afterthought in work that begins so conceptually. But this also reflects a view of the city as a human stress test: an environment, increasingly determined by technology, that affects our behaviour, and forces us to adjust. Flamand is both fascinated and unphased by this situation, and like many contemporary choreographers who make austere work (William Forsythe and Yvonne Rainer spring to mind) Flamand seems like an optimistic sort. “It’s a confrontation,” he says cheerfully. “I’m not a technophobe or a technophile. We have to work with the machine we have created, so if we want to create a certain humanity, we have to battle with that.” Some confrontations have been more difficult for his dancers than others. Jean Nouvel’s vast structure for 2001’s Body/Work/Leisure, based on the architect’s love of orthogonal systems, turned Flamand’s company into cage dancers. “It’s a work about constraint,” Flamand says. Other architects have used the space more freely. After Jean Nouvel’s cells, Flamand’s work with Thom Mayne, “was about how space can dance. Because the structure was much more open and liberated the space.” For Silent Collisions, the piece Flamand made for the 2003 Venice Biennale, Thom Mayne created a kinetic set, based on an installation he’d shown earlier at NAI Rotterdam. Mayne says, “I was interested in producing a dynamic site that was in collaboration with the movement. And so there was a reciprocity between the site and the dancer.” The set made of steel sections and powered by servo electrical motors began as a compressed cube before very slowly opening up to create different spaces for the dancers to negotiate. Mayne says, “There were a lot of issues involved because the dancer had to know the location of the space; it was a very volatile environment. And at its lowest point, we produced a space that was about a metre high and so the movement of the body was very horizontal, very ground-oriented.” Flamand has had a knack for approaching architects at key points in their career: Diller and Scofidio before they started to build; Hadid on the verge of stardom … Flamand says, “It was a fantastic moment because she had a lot of time … we worked like a Renaissance atelier. Hadid had the time to design not only the set – three lightweight metal bridges which the dancers pushed around to create new spaces and even wore as skirts – but also the costumes. Perrault takes a slightly poignant view of the difference between his normal architectural work and his adventures in choreography. “The creative commitment, it’s exactly the same. But after the show, the show disappears.” But Flamand’s enthusiasm for architecture is so obvious that it’s unsurprising that Mayne says, “I’d love to do it again … it took us different places we just hadn’t been before.” And Flamand firmly believes that thinking about people – as bodies in movement – is useful for making cities: “Dance is a very strong medium to speak about the world today.”

credit Morphosis, courtesy of Ballet National de Marseille |

Image Pipitone, courtesy of Ballet National de Marseille

Words Fatema Ahmed |

|

|

||