|

|

||

|

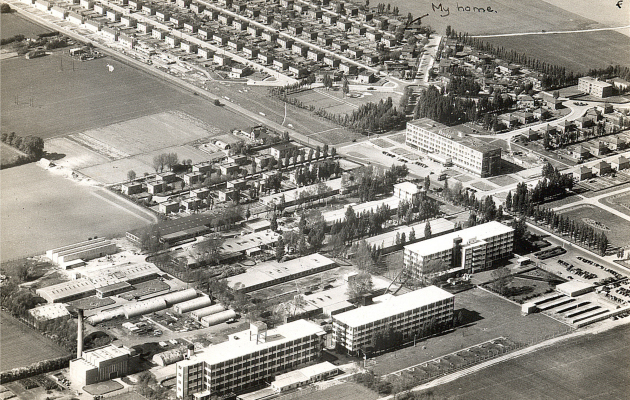

Icon 149 looks at Essex’s modernist tradition, but in its approach to housing the borough has proved its radical credentials since the early 20th century. There’s plenty of everything in Essex except complacency. In Icon’s November issue (149), Charles Holland celebrated its accomplished modernism (though I’d add the grittier factory village built at East Tilbury in the 1930s by Bata Shoes to his selection), and during the 20th century the county tried everything to house new settlers, drawn out of east London down the railway arteries and the grid of trunk roads (reading from west to east, the A11 to the A13). In September, Doughnut: The Outer London Festival put the focus on the periphery, as it was and as it is. With the population of London finally reaching pre-World War Two heights, which way will the gravitational pull go next? Crossrail, the one gigantic public infrastructure project that brooks no obstacles, will soon reach into the heart of Essex, terminating at Shenfield. But this won’t presage a return to the kind of leafy garden suburb dreamed up a century ago; rather the eager release of brownfield land to volume house builders and, if recent developments are anything to go by, an almost complete absence of infrastructure – public transport, medical centres or schools in the places where they are needed. Back in 1910, an ambitious and enlightened Essex landowner, Herbert Raphael, promoted his own garden suburb in which the housing, if not the amenities and employment opportunities, aimed to compete with the First Garden City at Letchworth. Romford Garden Suburb, built on the old Gidea Park estate, began with a cottage exhibition, dominated by esteemed Arts and Crafts architects and commemorated by a catalogue of testimonials from the left-leaning great and good: Fabians, Millicent Fawcett and other pioneer women (including the first female electrical engineer), and even Thomas Hardy, architect. These were to be well-designed, ergonomically efficient family houses. They were for sale at reasonable prices. Romford and Gidea Park soon became seamless adjuncts to metroland. The interwar and immediately postwar out-of-town estates (built for tenants both of the London County Council and of its successor the Greater London Council) were to be a very different affair. They housed populations relocated from the dense terraces of Stepney, Tower Hamlets, Poplar and Newham, which had been bombed or else demolished as substandard and irredeemable. In fact, more than 25 per cent of Michael Young and Peter Willmott’s subjects in their study of Bethnal Green families, published in 1957 as Family and Kinship in East London, had already turned tail and returned (presumably at their own cost) from the drab cottage estate at Debden to their familial networks in inner east London. By then Harlow was growing into a substantial New Town (as was Basildon), and new business and commercial opportunities, along with a full range of amenities, were as important as decent quality housing. But, as David Matless points out in Landscape and Englishness (1998), this was a version of a model society in which the role of women had diminished. The wife and mother was back indoors, and her delight in a well-equipped home would soon pall. Now life became homogenised. In the 1970s, Essex County Council made its own effort to raise the quality of volume house building in the county. The Essex Design Guide was soon to be diluted, then despised, and is now largely overlooked, in residential design at least. However, it presented a useful set of tools, a visual check-list governing massing, form and materials. Its best results were in small village infill schemes; its most ambitious, though least architecturally successful, a small new town, South Woodham Ferrers, initiated in 1972. Even if the town centre focused on a superstore, compared to the sad wastelands of the now moribund Thames Gateway, launched 20 years later, and in particular its fragmentary, beached remnants at Barking Riverside, it had the modest virtues of a planned, mixed development in a pleasant setting. |

Words Gillian Darley

|

|

|

|

||