|

|

||

|

Part treatise, part memoir, part moan, this latest book from the doyen of Finnish architecture makes a case for craft, touch and memory, says Tom Emerson. After a crit I attended recently, one of the guests described a student as having “intelligent hands”. The work presented did not display exceptional craftsmanship either in drawing or making but the comment described precisely a latent knowledge of the world. The student was clearly extremely sensitive to both the meaning of high art and culture and the accidents and repairs found in everyday life, which although not necessarily life-enhancing, enrich the world with imagination, resourcefulness, humour and pathos. Juhani Pallasmaa’s latest book, The Thinking Hand, speaks exactly to this world. The notion of the “thinking hand” only forms a small part of the text, which is dedicated to a wider exploration of existential knowledge in architecture and art. Part lesson in architecture and part philosophical memoir, the book is a call to arms for a return to a fully embodied design process in which knowledge and experience are fully assimilated within the designer and are returned through touch, gesture, habit and intuition. Pallasmaa devotes the beginning of the book to an exploration of how the hand operates as partner to the eye and the brain. Pallasmaa describes in minute detail the surgeon’s mesmerising transfer of knowledge from the brain to the hand and connects this process to all forms of knowledge, from the development of tools to language itself. Pallasmaa travels through the life of the hand with essays on craft, drawing and of course communication and symbolism. The need for a fully embodied design is the most often repeated thesis coming out of these case studies, which are generally compelling but weighed down by the implicit correlation between craft and virtue. Pallasmaa’s resistance to digital technology further ties the narrative in knots: many paragraphs begin with “I don’t mean to sound like a Luddite but …” (or words to that effect) only to follow with a diatribe against the ills caused by our overly digitised world. These rather naive passages reinforce his pious comments about craft and his teacherly tone. The book is unlikely to be useful to architects outside his flock. Its ambition brings to mind short meditations on architectural themes such as In Praise of Shadows, Species of Spaces, Invisible Cities or Pallasmaa’s own rewriting of Calvino’s Six Memos for the Next Millennium. But all of these offer the subject to the reader in a speculative and open way that has made them classics among architects and artists. The values he espouses are already, as he would put it, “embodied” within the architects who share his views and cannot be learned from a book. And even if they could, this one is too prescriptive to inspire you. In a later chapter about “Emotion and Imagination” he explains that imaginary and real experiences are processed by the brain in exactly the same way “that mental images are registered in the same zone of the brain as visual perceptions, and that these possess all the experiential authenticity of those perceived by our own eyes”. At this point the narrative becomes more philosophical, invoking memory as a central font for the imagination. Initially the idea of memory emerges in the torrents of references and quotations that infuse the book. Pallasmaa then lays down his own memories of a life immersed in art, literature and architecture with such urgency it’s as if he is about to forget them: Tarkovsky, Michelangelo, Calvino, Dostoevsky, Giacometti, Titian, Van Gogh, Rilke, Moore, Matisse, Cezanne, Merleau Ponty are just a few of the names invoked. The early didactic tone takes on a strangely hypnotic rhythm which appeals to the reader’s senses and towards the fragility of the embodied knowledge he is trying to protect. The roll-call of artists and poets is no longer important; it matters little that I am not so moved by Henry Moore’s inflated monumentality or Renzo Piano’s bogus claim to craftmanship, it matters that he stitches his narrative together with recollections and experience. The ability to absorb knowledge into one’s whole being before forgetting is Pallasmaa’s obsession and provides a timely, poetic conception of architecture as both haptic – represented by craft – and linguistic – fine art and literature in particular. In short it is a meditation on the existential use of knowledge in making the world.

|

Words Tom Emerson |

|

|

||

|

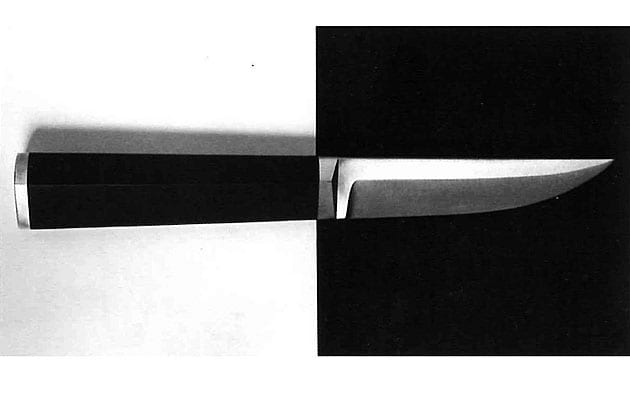

Knife by Tapio Wirkkala, 1961 The Thinking Hand, by Juhani Pallasmaa, Wiley, £24.99 |

||