A gathering at the Mleiha Fort during the Sharjah Architecture Triennial. Photo by Priya Khanchandani

A gathering at the Mleiha Fort during the Sharjah Architecture Triennial. Photo by Priya Khanchandani

The first ever Sharjah Architecture Triennial, curated by RCA’s Dean of Architecture Adrian Lahoud, engages with the challenging issue of ‘rights of future generations’. But engagement with rights of UAE residents is missing, writes Priya Khanchandani

As we drive east out of Sharjah, high-rises give way to patchy sand dunes interspersed with villas, and then finally the clear, sandy terrain, interrupted only by the road by which we have arrived. About a hundred people are gathered here in the desert, basking in what’s left of the day’s sun, beside the ruins of Mleiha Fort.

Then, a mellow sound of rumbling emerges, like rocks tumbling far in the distance. We glance at the apex of the Hajar Mountains, whose lower ranges are visible to us, but everything is as still as a picture-postcard. Could the source of this moody drone be beyond our sight? Gradually, over the course of a half an hour or so, it grows closer, until it feels as though it is beneath us; unfolding within the subterranean graves that we are sitting atop. As we contemplate the sound, the sun begins to set over the mountains, casting an iridescent orange glow over the desert.

The rumble isn’t generated by the ground, although its source is located there. It is an experimental sound performance as part of the public programme for Sharjah Architecture Triennial, which comprises exhibitions and installations, as one would expect, but also rituals, processions and events like this: a set by Nicolas Jaar, the Chilean-American DJ and producer, evoking the desert landscape. It is a site where archaeologists have excavated monumental tombs and learnt of historic settlements. But rather than removing objects from the earth, Jaar has buried 16 speakers around the fort, creating an immersive sound experience.

Ngurrara artists producing Ngurrara Canvas II at Pirnini, May 1997. Photo by K. Dayman (Ngurrara Artists and Mangkaja Arts Resource Agency)

Ngurrara artists producing Ngurrara Canvas II at Pirnini, May 1997. Photo by K. Dayman (Ngurrara Artists and Mangkaja Arts Resource Agency)

At some point during the hour, Jaar stops the audio abruptly. He tells the audience that he simply can’t do justice to the landscape – which is frankly breath-taking – and asks us to simply listen. We sit meditatively, observe the endless desert and feel the terrain beneath us. (We do so without the influence of any mind-altering substances.) The performance is intended to evoke the inheritance of culture and ancestral land rights beyond the conventions of the land ownerships; subjects that recur elsewhere in this inaugural edition of the Triennial. For instance, one of the main exhibits back in Sharjah is the Ngurrara Canvas II, a painting produced in 1997 by a group of artists in support of their native title claim over vast stretches of sandy desert in Western Australia. Showing at Sharjah Art Foundation for the duration of the Triennial, it is one of the largest and one of only a few examples of a painting having been successfully used to assert land tenure.

After sundown, we enter the fort and watch the screening of O Horizon by the Otolith Group, a film made in Santiniketan Sriniketan, the home of the famous Bengal art school, which concludes with the rising of the sun. It is one of the most beautiful moments I have experienced at a design or architecture event, even if the fact of being immersed in the landscape seems to be only a tangential reference to architecture itself.

It is clear that the Triennial’s curator, Adrian Lahoud, subscribes to an expansive notion of architecture and that the land itself is a significant component of it. The title of the Triennial, Rights of Future Generations, is explained in Lahoud’s curatorial statement as being about the inadequacy of the expansion of ‘rights’ in recent decades to ‘address long-standing challenges around environmental change and inequality.’ Although issues of rights to land and climate change are recurrent themes, like many biennales, the theme is not always the most interesting thread.

Al Qasimiyah School Sharjah. Photo courtesy of Sharjah Architecture Triennial 2019

Al Qasimiyah School Sharjah. Photo courtesy of Sharjah Architecture Triennial 2019

The main location of the Triennial (even if its spiritual home is the desert) is a charming abandoned two-story school in Sharjah, where former classrooms and courtyards take on the role of galleries. Continuing in the vein of the desert, artists Cooking Sections have experimented with plants that can grow in arid climates and do not require the quantities of water and irrigation needed by the grasses and other foliage that are often used to adorn public spaces in the UAE. Working with engineers AKT II, they have prototyped a new model of non-irrigated urban garden for Sharjah and other cities with desert climates, which is installed in the grounds of the school. Research like this feels urgent in a country where high rises filled with air conditioning have become the norm. Meanwhile, spaces that work with the climate, including the school where the installation is located, are left disused.

An installation by architect Marina Tabbasum also refers to the relationship between architecture and its context. It comprises a series of three structures inspired by temporary dwellings found at the confluence of the Padma, Meghna and Jamuna rivers in the south of Bangladesh, which have to be dismantled and rebuilt constantly as the boundaries of the waters shift. A series of films installed in one of the structures relates the lives of inhabitants who keep their memories alive with stories rather than belongings and live in a constant process of adjustment. It is a warning that as our treatment of the planet causes our ice caps to melt, the boundaries of our seas will move inwards and force more of us to become mobile.

Marina Tabassum’s contribution highlights the impact of climate change in Bangladesh. Photo courtesy of Marina Tabassum Architects

The politics of domestic architecture is the subject of a poignant piece by Public Works. In a dimly lit gallery, five small desks illuminated by desk lamps are covered in archival material that tells the story of maids in Lebanon. We learn that their subjugation is heightened by the architecture of maid’s rooms, which are exempt from building regulations. Devoid of windows and tiny in size, they become disturbingly inadequate spaces of confinement. In many places in the Triennial including here, the onus is on the visitor to engage with the minutiae of the material in order to unravel the narrative raising questions about audience engagement, although for those with the inclination to make the effort to do so, it does pay off.

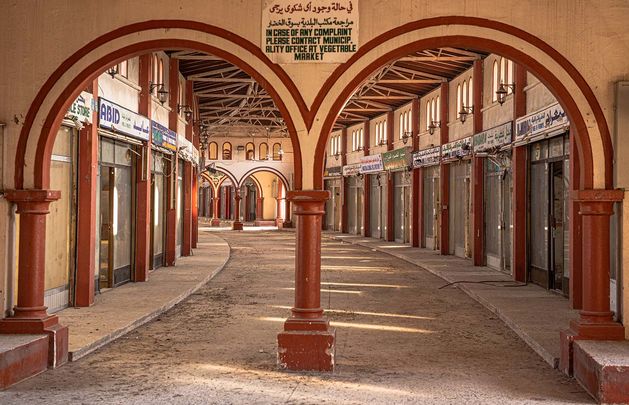

Sharjah Vegetable Market is one of the formerly disused venues repurposed for the exhibition. Photo Courtesy of Sharjah Architecture Triennial

Sharjah Vegetable Market is one of the formerly disused venues repurposed for the exhibition. Photo Courtesy of Sharjah Architecture Triennial

A disused market that has been superseded by the city’s air-conditioned malls is another Triennial site. Among the installations are a series of eight models depicting archaeological sites in the ancient city of Sebastia in Palestine. The sites have been excavated and had their histories torn apart by institutions like the Israeli Civil Administration. We learn that at the Temple of Kore (which dates to the third century CE or even earlier) is currently buried under an olive orchard often frequented by looters at night. The use of models that represent the negative space revealed by the act of excavation makes evident the violence involved in the mistreatment of Palestinian culture and its histories.

Many of the most intriguing projects concern social and political issues shaping the Middle East and the Global South, which is a research interest of Lahoud, who is the Dean of Architecture at the Royal College of Art. However, it is surprising in light of the Triennial’s curatorial statement and emphasis on ‘rights’, that it does not more overtly address the values system that underpins the availability of rights in the UAE. For instance, it is a place where the rights that are a prerequisite to an impartial exhibition, such as freedom of expression, are not necessarily a given. The inaugural Sharjah Architecture Triennial is successful in terms of its willingness to engage with the issues that shape architecture in geographical areas that are all too often overlooked, but it could have been more self-reflexive about the troubled politics of its own context.