|

Harvey Wiley Corbett’s Elevated City, 1930 (image: phantomcity.org) |

||

|

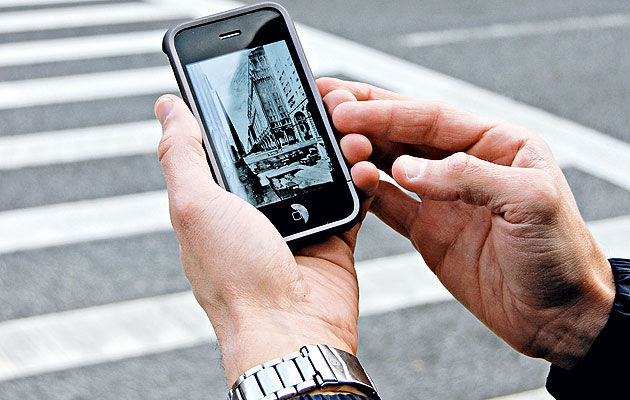

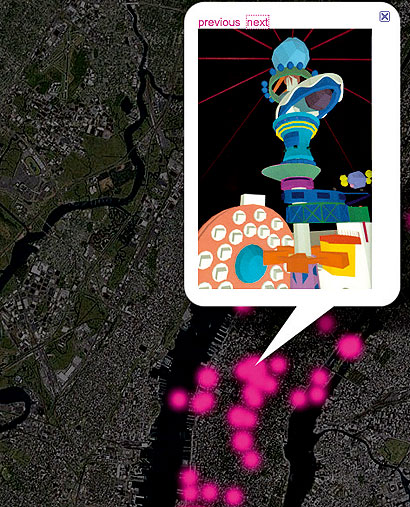

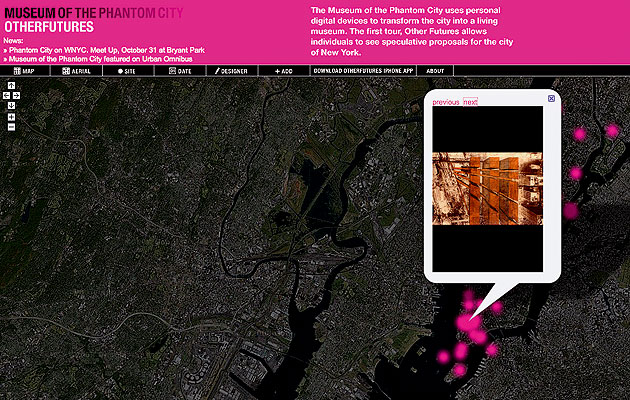

The New York that might have been is now on your iPhone. Geoff Manaugh went exploring If every city has other, fantasy versions of itself lying just beneath its surface – a Dickensian London, the streets of Raymond Chandler’s Los Angeles, Allen Ginsberg’s Moloch-haunted New York, the Paris of Amélie – then how can we access these hidden cities more easily? How we do visit a place that exists only in parallel to the one we inhabit? Museum of the Phantom City, an application for Apple’s iPhone which debuted as a free download in October 2009, offers one possible approach. Sponsored by New York’s Van Alen Institute and designed by Irene Cheng and Brett Snyder, Museum of the Phantom City puts architecture’s speculative, impossible, or simply yet-to-be-realised projects out on the streets where they belong. Cheng and Snyder wanted to curate a tour of the city, but in reaction against what they call the “technologically primitive … 19th-century forms of the plaque and the guidebook,” they decided instead to explore the spatial possibilities of a handheld device (read iPhone). But their innovation went further. Rather than retell the story of famous parks and monuments, Cheng and Snyder came up with a far more interesting proposal: a tour of the New York that doesn’t really exist. Their application enables users to discover unrealised projects – by Steven Holl, Superstudio, Hugh Ferriss, Archigram, Buckminster Fuller, Rem Koolhaas, and many more – in situ around the city. Pink dots on the iPhone screen represent projects; white dots mean something will be added to the map soon. You can thus roam around the city with your phone held out in front of you like a dowsing rod, detecting literally fantastic architecture in blurred outlines on all sides. Little-known projects like “Foodopolis” – a 2009 proposal for “floating hydroponic farms” by Phu Hoang – share the cityscape with classic, black-and-white visions of a multilayered metropolis. Moses King’s 1908 vision of the city, for instance, shows us vast bridges criss-crossing the cavernous avenues of a fully remade New York. Small passenger airplanes buzz past the windows of unsuspecting skyscrapers. Or take Harvey Wiley Corbett’s Manhattan: 90 years ago, Corbett wrote that “Pedestrians will move about through arcaded streets, out of danger from traffic … Walking would become a pleasure … the overwrought nerves of the present New Yorker would be restored to normality, and the city would become a model for all the world.” These visionary alternatives are now as accessible to everyday pedestrians as reviews for local pizza restaurants and bars. On the other hand, the presentation and user interface of Cheng and Snyder’s Phantom City could still use some work. There is very little dynamism to the presentation of each project; you’re left staring at two or three JPGs and some stationary text (often no more than 75 words). You’re not navigating an immersive world of spectacular buildings, in other words, but standing on the street, holding an iPhone, waiting for something to happen. Further, external links – even to Wikipedia pages about the architects or the neighbourhoods their projects are meant to appear in – would not be out of place. But it says quite a lot about the state of architectural design today – and about the vitality of the market in independently developed iPhone apps – that something as simple as Phantom City could re-energise how we present and publish spatial ideas. Indeed, one of Phantom City’s most interesting implications is that it might be a model for a new kind of publication. Why try to get your speculative design for a new museum published in a glossy architecture magazine when you could simply stick it in everyone’s iPhones, firmly located in its urban context and publicly accessible from the uploaded world of augmented reality? It’s an exciting idea: graduate thesis projects could sit alongside real buildings by Bjarke Ingels or OMA, and as yet impossible structures from fantasy and sci-fi could form an integral imaginative layer within the city. Perhaps someday we’ll be done with monographs altogether; travelling exhibitions and even year-end studio reviews will be a thing of the past. We’ll simply upload our projects into something like Museum of the Phantom City and let the world decide their worth. After 20-odd years, the most cherished imaginary buildings could even qualify for landmark status. Activist reconfigurations of the urban landscape won’t require billionaire patrons but designers well-schooled in C++.

Screenshots from the Phantom City website (image: phantomcity.org) |

Words Geoff Manaugh |

|

|

||

|

Screenshots from the Phantom City website (image: phantomcity.org) phantomcity.org |

||