|

|

||

|

Women designers have been all but written out of the history of modernism, but now an ambitious show at MoMA aims to set the record straight. Claire Barliant finds out if it succeeds In the early 1920s, designer Eileen Gray was encouraged by her partner Jean Badovici to try her hand at building. Despite her self-described lack of training, she took up Badovici’s challenge, and spent three years building E-1027 (a cipher for their entwined initials) on a beachside site in the south of France. The blindingly white house has a central area for entertaining, smaller rooms to enhance privacy, and fenestration to capitalise on ocean views. A few years later, Le Corbusier, a friend of the couple, painted eight murals on its walls while staying at the house. Gray deemed this ‘an act of vandalism’ to a project she felt expressed modernism’s rejection of decoration. The friendship soured and, in 1952, Le Corbusier built his storied Cabanon a stone’s throw from E-1027. He later drowned while swimming in the sea just below the two houses.

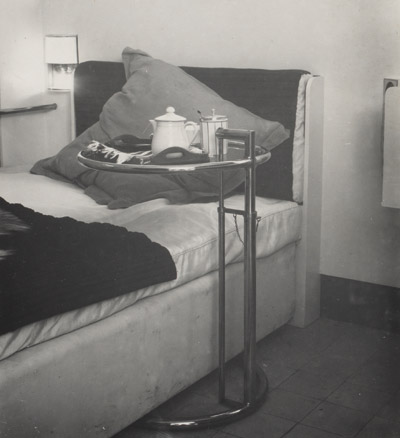

Guest room at Eileen Gray’s E-1027 with adjustable table A poetic video about the episode, with stills of the house and letters among the three, features prominently in the Museum of Modern Art’s How Should We Live? Propositions for the Modern Interior. Its ambitious goal is not only to reveal modernism’s impact on domestic space, but also to explore women’s contributions to design and architecture in the first half of the 20th century. These have long been overlooked, partly because women’s contribution was less as producers than as facilitators. They played crucial roles as clients or assistants, taking back seats as male practitioners gained status and acclaim. The role of ‘helpmate’ is not easy to explain in an exhibition format. Wall texts diligently plot relationships that led to profitable partnerships, such as Florence Knoll poaching Herbert Matter from the Eameses’ studio. He became the company’s visionary, directing its identity as well as the store’s legendary displays, one version of which is recreated. Another crucial supporter of avant-garde design was American textile designer Marguerita Mergentime, who hired Frederick Kiesler to design her apartment. MoMA’s re-creation of the result is somewhat lacklustre, mining pieces from its collection, such as Kielser’s biomorphic nesting coffee table in cast aluminum of 1935–38. Some design partnerships did transcend sexist boundaries (and not just that of Charles and Ray Eames, which is well represented). An effective display showcases Charlotte Perriand and Le Corbusier’s 1959 collaboration on bedrooms for a residence hall for Brazilian students at the Cité Universitaire in Paris. Perriand’s versatile contributions, including an elegant room divider that doubles as a wardrobe and bookshelf, are examples of modernism at its utilitarian finest. There is also a re-creation of Lilly Reich and Mies van der Rohe’s Velvet and Silk Cafe from 1927, purportedly the first time the public had the opportunity to sit on tubular steel chairs with no back legs.

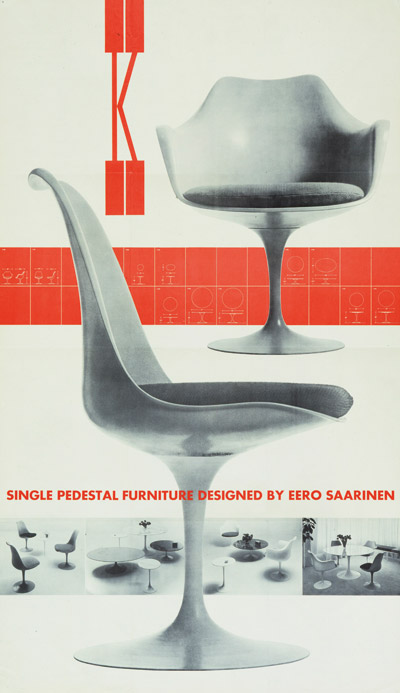

The Pedestal Collection by Eero Saarinen (1957), commissioned by Florence Knoll The show provides a means to highlight MoMA’s collection, thus marquee names and iconic pieces tend to obscure lesser-known figures. Aino and Alvar Aalto together helped found Artek, a retail store and design company. Aino led the interior design division, but the main works on view are Alvar’s furniture. Similarly, work by individuals, such as Eileen Gray’s earth-tone Moroccan-style rugs, Noémi Raymond’s Japanese-inflected textile designs and Clara Porset’s blueprints of sinuous furniture (co-designed with her husband, Xavier Guerrero), tends to be overshadowed by objects made by more famous male designers working in collaboration with female ‘helpmates’. One project designed exclusively by a woman does receive pride of place: Grete Lihotzky’s Frankfurt Kitchen (1926–27). The earliest design by a woman in MoMA’s collection (and a recent acquisition), it is installed in a freestanding room with windows and doors for viewers to peer through. The Austrian architect had never cooked before, but was inspired to create a kitchen as she believed a more efficient layout would lift the burden of housework on women, and help them in their struggle for independence.

The newly restored Frankfurt Kitchen (1926–27) by Grete Lihotzky After interviewing women about kitchens and doing time-motion studies, she came up with a compact design loaded with storage space, such as cabinets for dishes and small steel drawers for perishables. Lihotzky, whose decision to pursue architecture in 1916 was unheard of for a woman, later worked with Adolf Loos on housing, and spent four years in prison during World War Two for her work in the resistance. Such moving stories – Lihotzky’s political activity, Gray’s successful interior-design business – tend to get buried in the mass of material. One has the distinct sense that MoMA is working hard to round out its collection and tell a more complete history of design and architecture. In the 1930s, its curators focused on acquiring American design rather than the international style, and the show almost seems like a belated apology. But the timid thesis, ostensibly about modernism’s influence on the home, with an emphasis on women designers, leads to a tepid exhibition. We can only hope that this broad overview is laying the groundwork for more in-depth, individual analyses of these bold women who championed modernism and its ideals of independence and democracy, all the while struggling against the biases of colleagues and communities. |

Words Claire Barliant

Above: Lilly Reich and Mies van der Rohe’s Velvet and Silk Cafe for the Women’s Fashion Exhibition in Berlin (1927)

How Should We Live? Propositions for the Modern Interior |

|

|

||