|

|

||

|

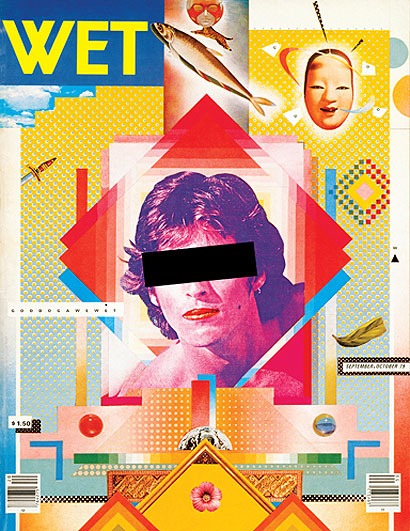

At the end of his MA in architecture at UCLA, Leonard Koren strayed into “bath art”. This essentially involved taking pictures of models bathing in mud, water, hot air and steam, and then holding bathing parties to thank them. The side effect of all this moist hedonism was a “gourmet bathing” scene centred on Koren and his artist friends in Venice, California. The magazine WET: Gourmet Bathing & Beyond was an initiative to capitalise on the scene’s buzz. “Gourmet bathing” is perhaps best explained by adopting words from the letters pages of the magazine – it’s an “attitude”, an “absurd sensuality”, an “unintelligible conceit” that revels in pleasure, ritual, taboo, and the experimental. Gourmet bathing is “a parody of all enthusiasms taken a bit too far”, or modernism’s obsession with hygiene transformed into a postmodern fetish. The first issue of WET appeared in May 1976 and comprised two folded photocopied 11″x17″ sheets with a print run of just 600. It quickly grew into one of the coolest new wave/proto-postmodern magazines in the world featuring fashion and music – especially British punk and new wave – and introducing new talent to the world. Matt Groening (of Simpsons fame) drew cartoons for it and Richard Gere appeared topless on the January/February 1980 cover. Its avant-garde phase lasted until late 1978, with each bimonthly issue containing at least some material concerning gourmet bathing.

Besides water, architecture was the other persistent interest and it published early Thom Mayne, Michael Rotondi and Michael Sorkin, and Frank Gehry in his corrugated iron period. A oversized format with lower quality paper was introduced in 1979. This format endured 10 issues and the magazine increased in acceptance beyond the avant-garde, reaching a circulation peak of more than 25,000. Debbie Harry adorned the July/August 1979 “outlaw” issue, the first to have no gourmet bathing content. Although WET hadn’t become complacent, it had become established. Koren’s book openly describes how the magazine during this period began to be driven by commercial decisions rather than by passion. After the first issue, WET had always been published as an entirely normal magazine, complete with advertising and reader questionnaires, but held off-the-wall content presented with cutting-edge graphics. Towards the end it became more sensational, featuring, for example, porcine copulation on the cover and an article on necrophilia. Advertisers flinched and stockists refused to stock it. Koren saw that the magic was gone and rather than sell, he killed his baby at the end of 1981 and moved on. The book Making WET is a desirable design object in itself. It resists a retro feel by omitting most of the signs of the times such as adverts, fashions and almost all the airbrush and marker-pen graphics. It is also beautifully produced on matt paper, with matt-printed hard covers and full-bleed images of reproduced photographs and pages from the original magazines. The backstory of the magazine and its personalities is interwoven throughout and reading this alongside the magazines begins to explain the trajectory of their form and content. There is little unpublished archive material, however, and more of this would have been welcome. As the title of Koren’s MA thesis was “the role of architectural education as preparation for the magazine publishing business”, WET magazine could be considered an architectural project. This book is less an architectural history than post-rationalisation, but it’s an explanation of the rise and demise of a very specific architectural movement cleaned up for 21st century consumption and a masterclass in avant-garde magazine production. Making WET: The Magazine of Gourmet Bathing by Leonard Koren, Imperfect Publishing, £24.95. |

Image April Greiman and Jayme Odgers

Words Steve Parnell |

|

|

||