|

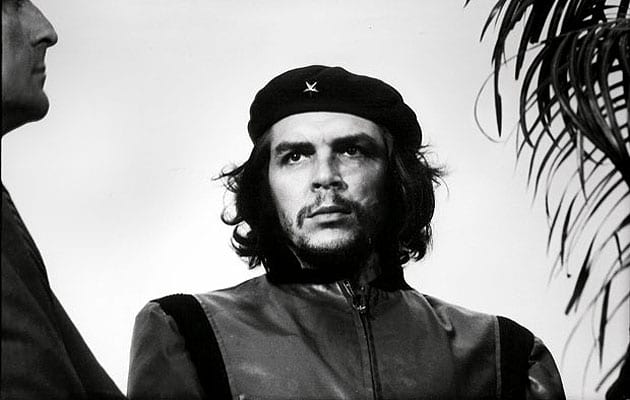

Korda’s 1960 photograph (image: Guerrillero Heroico © Courtesy Diana Diaz, Korda Estate) |

||

|

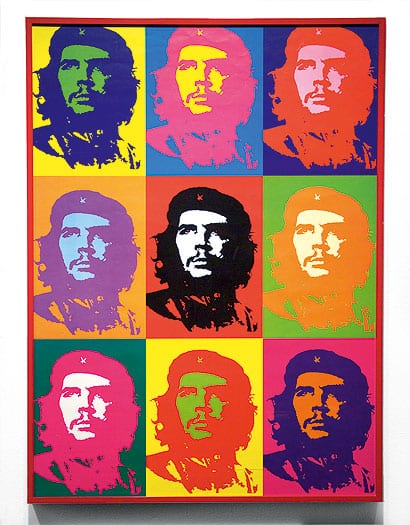

The story of the world’s first viral image is a strange and fascinating one, says William Wiles The face of Ernesto “Che” Guevara is one of the most reproduced images of all time. It’s instantly recognisable, a bearded, beret-wearing revolutionary, staring into middle distance from millions of T-shirts and walls. The eyes are determined, even fierce, but also soulful. The long hair inevitably suggests Jesus Christ, Che’s only serious competitor for worldwide brand penetration. Unlike Christ, Che doesn’t have a globalised bureaucracy doing his PR. Instead, he achieved ubiquity because … well, why exactly? Chevolution, a new film by Trisha Ziff and Luis Lopez, sets out to tell this story. First, however, it has to tell the story of Che Guevara himself, because the proliferation of his visage has not been accompanied by widespread knowledge of who he was. There are people wearing Che T-shirts who couldn’t name the man, let alone explain what he stood for. And the story of Che – his travels, how he assisted Fidel Castro in overthrowing the regime of Fulgencio Batista in Cuba, his later disappearance – is very romantic, an important part of his cult. The other life story in Chevolution is that of the man who created the image, Alberto Korda – a fashion photographer when Havana was the playground of the Americas who became a photojournalist before Castro gatecrashed in 1959. In 1960, Korda attended the mass funeral of the victims of La Coubre, a ship that exploded in sinister circumstances in Havana harbour. Che appeared on the speakers’ podium only long enough for Korda to take two photographs. Neither appeared in the next day’s paper. After Che’s disappearance in 1965, he briefly became a kind of Scarlet Pimpernel figure, rumoured to be fighting capitalism everywhere: in Vietnam, in Europe, in Africa. Che was killed by the Bolivian government in 1968, but the photograph – simplified into screenprint chiaroscuro – had already achieved immortality as his avatar. Spreading fast as a symbol of protest during the student unrest of 1968, it became a universal symbol of protest and resistance. Today we would say that it “went viral” – the whole story feels like a portent of the internet’s fevered culture of memes and mashups – and as it reproduced across the world, it started to mutate. From political statement, it was appropriated first by art, then by consumerism. In the hands of pop culture, the meaning of the image became utterly plastic: for Zapatista guerrillas in southern Mexico he’s still a hero of Marxist insurrection, while for young Republicans on American college campuses, he’s a symbol of the all-conquering power of capitalism, a system capable of absorbing its enemies in order to sell T-shirts. For most, however, the Che image is a convenient logo for generic youthful defiance of authority, a non-musical Cobain complete with early death. Even Che’s features are only optional – the frame of the beret and hair The film suggests that the neutrality of the image – Che looks curiously raceless, for instance – was an important part of its success. Now it has become an off-the-peg brand suggesting a conformist kind of individualism and an unthreatening kind of rebellion. It’s appropriate to an age where ideology has dwindled to identifying one’s consumer niche, rather than trying to change anything. It’s the Nike swoosh of political statements, a shape to which the user can attach any sentiment they like, and this fascinating film is an overdue examination of its strange story.

Che as pop art |

Words William Wiles |

|

|

||

|

Che on the chest of a Zapatista guerrilla (image: T-Shirt Photo © Ortega) Chevolution is at the ICA, London, 18-30 September |

||