|

|

||

|

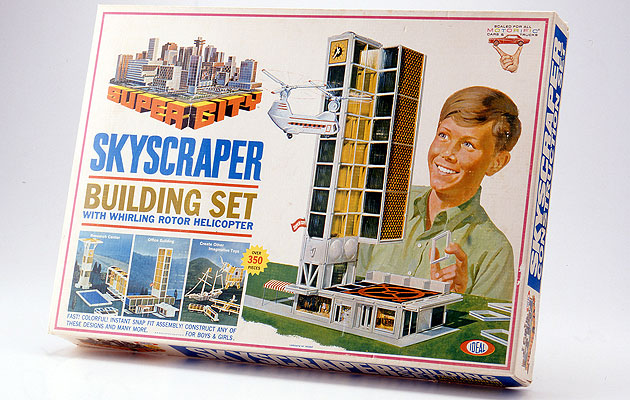

It is no coincidence that Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright and Buckminster Fuller were all taught in kindergartens, the school system that introduced building blocks into educational play. In these simple forms can be seen the first traces of modernism – the start of a relationship between architecture and the creative games of children that continues to this day. Construction toys, such as Lego, Erector Set and Meccano, allow children to create an infinite range of structures that test the limits of stability. The child presides over an imaginary universe of his own invention, able to dominate (and destroy with a flick of the wrist) a reality that normally dwarves him. Plato advised that future architects should play at building houses as children and, indeed, most architects learned the laws of gravity, physics, engineering and omnipotence playing with these kits. The sets, which have a long history, were conceived as philosophical toys: they were intended to amuse and serve an important educational purpose. In so doing, they played a crucial part in shaping the modern world. In Inventing Kindergarten (1997), the New York sculptor and architect Norman Brosterman argues that the pedagogical tools used in the second half of the 19th century might be interpreted as having laid the ground for geometric abstraction in art and architecture. Brosterman convincingly shows that the 20 “play gifts”, or architectural toys, used by the German crystallographer and pedagogical revolutionary Friedrich Froebel to teach children an appreciation of abstract patterns were the building blocks of modernism. In 1837 Froebel, who had studied architecture at Frankfurt University, started the original kindergarten school in the spa town of Bad Blankenburg with the aim of teaching children an appreciation of the god-given geometry underlying all life. After his death in 1852, the kindergarten system spread through Europe and its colonies, to America and the Far East. Piet Mondrian, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Buckminster Fuller and many other members of the avant-garde went to kindergarten schools and played with Froebel’s geometric toys. They sat at special gridded desks where they experimented with knitted balls, building blocks, coloured sticks, rings, mosaic tiles, and a rudimentary Meccano-type set made from toothpicks with dried peas for the joins. (Froebel thought existing construction toys, with their realistic, decorative custom-made parts, had a destructive effect on children’s imagination.) Brosterman claims that these modular games, with their emphasis on handicrafts and block play, formed “nothing so much as an introductory course in the mechanics of art and architecture … Froebel drew plans for educational tools that implicitly foreshadowed the actual buildings that Wright, Mies, Adolf Loos, and Le Corbusier would design when they grew up.”

credit Kiyoshi Togashi In his autobiography, Wright, who went to a kindergarten school outside Boston, and whose mother trained as a kindergarten teacher, acknowledged the profound influence this education had on him. He was taught not to copy nature but to appreciate the basic forms hidden behind appearances: “For several years I sat at the little kindergarten table,” Wright wrote. “The smooth cardboard triangles and maple-wood blocks were most important. All are in my fingers to this day … I soon became susceptible to constructive pattern evolving in everything I saw. I learned to ‘see’ this way and when I did, I did not care to draw casual incidentals to Nature. I wanted to design.” Wright wrote that these toys directly informed the organic abstractions and clean geometric lines found in his buildings and the regulating grids of their plans. (It is no surprise that their careful balance of interpenetrating forms lend themselves to being reimagined as architectural toys: you can now buy a kit that enables you to build Fallingwater in Lego pieces.) Wright encouraged his own children to experiment with Froebel’s “architectural boxes” as he had, and his wife followed Froebel’s method when she home-schooled their seven children in a classroom that Wright added to their home in Illinois. These toys also left their mark on them. In 1918, John Lloyd Wright, the architect’s second son, who followed his father into the profession, patented a building set known as Lincoln Logs. This popular game, which is still in production, allows children to build cabins and other structures with notched strips of Oregon pine. It was influenced by the construction techniques used in the foundations of his father’s earthquake-proof Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, which John worked on (before being fired by his father when he asked for a raise), and launched his second career as a toy designer. Le Corbusier, who went to kindergarten in La-Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, allied the international style with Froebel’s building blocks when he defined architecture as the “masterly, correct and magnificent play of masses brought together in light: cubes, cones, spheres, cylinders, or pyramids are the great primary forms which light reveals to advantage”. He described the Parthenon as a “sovereign cube facing the sea”, as if enlarging Froebel’s blocks to building size in his imagination. His Modulor system, patented in 1948, which sought proportional harmony in the mathematics of the human body, also owes much to Froebel’s gifts. At the Bauhaus, many of whose teachers had been educated at kindergartens, students were required to take a six-month course of abstract-design activities, which built on Froebel’s educational system, before they could begin work in the school’s specialist workshops. Indeed, the Swiss painter Johannes Itten, the Bauhaus’s master of form and colour, was a trained kindergarten teacher. The institution was itself reminiscent of a luxurious kindergarten. In 1924 Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus, had been invited to design a training school, research centre and monument to Froebel in Bad Liebenstein to open on the 75th anniversary of Froebel’s death. These plans were never realised but the scheme influenced the Bauhaus buildings in the central German town of Dessau that Gropius designed the following year. In the early 20th century many celebrated avant-garde architects – such as Josef Hoffmann, Bruno Taut and Hermann Finsterlin – created toys that tell the history of modern architecture in miniature. The Bauhaus, as one might expect, produced many such games (Swiss toy maker Naef still produces wooden replicas of many of these designs, including Alma Siedhoff-Buscher’s 1924 building game). These reflect some of the childish excitement their creators no doubt once felt playing with earlier kits, and taught a new generation an appreciation of industrial beauty, rhythmic pattern, modular structure and town planning. Frank Gehry recently lamented the decline of “creative play” in the architectural profession. It is this spirit of playful curiosity that carries over into the most innovative buildings. Santiago Calatrava, who had a voluminous toy box as a child, claims that he still plays with architectural toys as he looks for inspiration for his bridges and skyscrapers: “My approach to design begins with the creation of toys and games,” Calatrava once said, “that can give plastic expression to the principles of statics.” |

Image Spencer Hopkins

Words Christopher Turner |

|

|

||

|

credit Douglas Coupland |

||