|

Danish company Kvadrat has called on one of the biggest names in fashion – Christian Dior’s Raf Simons – to create its latest range of home textiles. But it’s the weavers at a mill in Huddersfield who are bringing the company’s designs to life on a daily basis This article was first published in Icon’s May 2014 issue: Factories, under the headline “Blank canvases”. Buy old issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this The Belgian designer Raf Simons is more versatile than most contemporary fashion designers. He studied industrial and furniture design and moved into fashion by working for Walter van Beirendonck, one of the “Antwerp Six” group of stern Belgian designers who emerged in the 1980s. He launched his own menswear brand in 1995 and was for seven years creative director at Jil Sander, a label known for its minimalist womenswear. Since 2012 he has had the highest-profile job in fashion – creative director of the historically flamboyant Christian Dior, the flagship of LVMH, the largest and most profitable luxury goods business in the world. This is a job so stressful that its pressures are partly credited with sending its previous occupant, John Galliano, into a spiral of depression and deplorable public behaviour. Recently, Simons launched a range of home textiles for the Danish company Kvadrat. It’s a mixture of upholstery fabrics – “blank canvases” Simons has called them – and a few finished products such as throws and blankets in wool, cashmere and mohair. Simons had in a way worked with Kvadrat, a specialist in contract upholstery, before; he used its cloth to make hard-wearing coats in his autumn/winter 2010-2011 collection for Jil Sander. Anders Byriel, the chief executive of Kvadrat, explains that, given Simons’ design training, a textile range isn’t as big a departure as it looks. “It was not something invented in an advertising agency or a communications department, it was actually something about Raf really liking our materials and not really knowing what Kvadrat was.” In addition to its rapidly expanding business working with specifiers and furniture manufacturers, in recent years the company has shown off its colourful textiles in a series of collaborations with artists and high-profile designers, which at first glance have no obvious commercial purpose. These include the custom curtains for Thomas Demand’s photography exhibition at Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie in 2009 and Raw Edges’ massive wood and textile installation at the Stockholm Furniture Fair in 2013. Byriel says, “So we thought this was good fun to have a high-end fashion client.” For once, however, there was more than personal interest and relationships involved – or a desire to test the company’s manufacturing abilities and develop new processes. In 2011, Fanny Aronsen the Swedish textile designer and professor at the Konstfack in Stockholm, died at the age of only 55. After a couple of years of wondering what to do with the textiles she had developed for Kvadrat, Byriel says it was then that they approached Simons to see if he would be interested in building on Aronsen’s work. The project may have been a welcome change from producing the five or six collections a year that Dior demands. As Byriel says, “For him [Simons], it’s been a space, a mental break – he’s been very engaged in the products.” But behind the publicity and praise for projects like this, the practical requirements of manufacturing remain. Kvadrat may have been founded and is still based in Denmark, but a majority of its woollen cloth is produced in the UK, specifically by a Huddersfield-based textile company called Wooltex, which was started by its owner Peter Timmins in 1996, and last year produced 1.5 million metres of cloth for the company. At the beginning of March, I was shown round the mill by Wooltex’s technical director, Richard Brook – described by Kvadrat’s quality and production manager Jesper Grandt as “the wing commander there”. Wooltex carries out all the warping, weaving and quality inspections, and subcontracts all the other functions, such as finishing, to local companies. In 2011, Kvadrat took a 30 per cent stake in Wooltex, and at the same time bought a share in Gaudium, the Dutch manufacturer that supplies it with synthetic materials (used particularly for polyester curtains). Wooltex produces two kinds of coloured cloth – colour-woven fabrics, where wool is dyed and blended before being woven into a single varied yarn, and piece-woven fabrics, where the woven cloth is white and goes to a local dyer to be coloured. The first method, used in a line such as the Divina MD, creates a depth of colour that’s not to be found in piece dyes, but it’s a more complicated process to get right. The warping and weaving machines are mainly German Dornier looms, with a few faster-weaving Belgian Picanor looms, which, Brook says, “will be dead in five years, but they’ll have paid for themselves”.

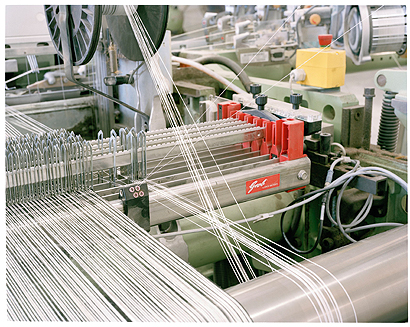

Yarn reels set up with a warp weaving loom Above the noisy warping and weaving floor, the rolls of fabric are then taken to the calm of the mending floor, where the menders undo and inspect every roll, and sort out any faults. Carol has worked as a mender for 42 years and it took her three years of training to know what to look for. Brook says, “One of my harder challenges is to get a new batch of menders to come through.” The area was once full of mills (many of which have been converted into luxury flats), which also ran schools that taught these skills. Now, Brook says that he’d have to rely on Wooltex’s current staff teaching on the job. The menders fix small tears by sewing in threads but, Brook says, “If the mending department is shouting at me that we’ve got a lot of problems, then I’ve obviously got a yarn problem.” A problem specific to the wool industry is contamination from the polypropylene bales in which undyed, unspun wool is stored. If the bales are punctured and get into white wool, the splinters can’t be detected until the woven cloth has been dyed. “It can take 15 minutes up to an hour to pick the polypropylene out of a piece.” Wooltex has several yarn suppliers, but one of the largest is a nearby family firm which does the dyeing and yarn spinning, R. Gledhill, which was set up in 1934. Peter Gledhill, one of the founder’s sons, points to the bales of wool in the factory sheds, encouraging me at one point to plunge my hand into an open bale of undyed cashmere; it’s as soft as it looks. The wool with which he makes yarn for Wooltex is quite different – its micron (short for micrometre) comes only from sheep in Australia and New Zealand. Typically, Brook explains, fine merinos producing 14 to 16 microns supply the yarn for clothing, but this wouldn’t last two minutes used in contract upholstery, which requires anything from 25 to 30-micron wool. The challenge for Wooltex is ever-greater efficiency. There’s a warehouse at Kvadrat’s headquarters in Ebeltoft where, surprisingly, all the finished rolls Wooltex makes are delivered. But since Denmark aims to hold smaller quantities of stock and, eventually, to deliver directly to some of its customers, Wooltex has learned to hold less yarn itself and to deliver orders more quickly – it currently aims to deliver 95 per cent of its orders on time. It can make a piece – a length of fabric 50m long, 1.5m wide – in two to three weeks, and a colour-woven piece takes roughly twice as long to produce. Brook says, “We could in theory be delivering in five days, if everything went well … Every now and again, you can do anything. But you can’t do anything all the time.” Still, Wooltex is critical to Kvadrat’s plans to become more “industrialised” – to build tailor-made supply chains. Since it was set up in 1968, the Danish company has always manufactured in part in the UK. The Danish textile industry, however, is another story – part of history, Byriel explains. “What lives on in some small pockets of Denmark is more like craftsmanship and handwork, but the Danish textile industry is long gone.” Byriel’s comments on what’s left of British textile manufacturing, on the other hand, are so complimentary that it’s hard to believe that it’s such a secret.

A German Dornier loom creating a warp at Wooltex

Wooltex menders checking the woven cloth

Polypropylene bales holding wool to be spun into yarn

Different coloured wool being blended before spinning

Wool blender at Gledhill: a recipe for grey

Gledhill’s thread -spinning machine |

Words Fatema Ahmed |

|

|