|

|

||

|

“Our work is not about design,” says Noam Toran, defiantly. We are more interested in ‘thingness’.” “We love film and short stories,” enthuses Toran, “because of their ability to distil major issues and generic themes in a pared-down form.” Toran and Kular met when studying Product Design at the Royal College of Art, where they both now teach. Their first projects together were meticulous exercises in film taxonomy, such as the dark catalogues of explosion and demolition clips in Violence and Destruction: A Film (2005) and death scenes in Proposal for an Impossible Library (2007). “We tried to dissect cinema into tiny little sub-sub-sub-categories, cutting it along different lines other than genre,” says Toran. Through this work, the pair became interest in the cinematic object – the prop as protagonist. This interest led to their next collaboration: a series of short film synopses and a set of related props in The MacGuffin Library (2008). The project is an homage to Alfred Hitchcock , who coined the word “MacGuffin” to describe a recurring object that is useless in itself, but around which the plot revolves: a key or a roll of microfilm, for instance. Continually exhibited and expanded, the MacGuffin Library is an archive of key symbolic objects, from Goebbels’ Teapot to Mickey Mouse’s urn, each displayed alongside a brief synopsis of an imaginary film. “By exhibiting these two fragments, we intend the viewer to become the third, triptych element in that relationship,” explains Kular. “You are the maker of the cinema, the creator of an extended story, by looking at the object and reading the summary.” Citing short story writers Jorge Luis Borges and Raymond Carver as their key influences, Toran and Kular’s work is grounded in the world of condensed storytelling, leaving the viewer to fill in the gaps.

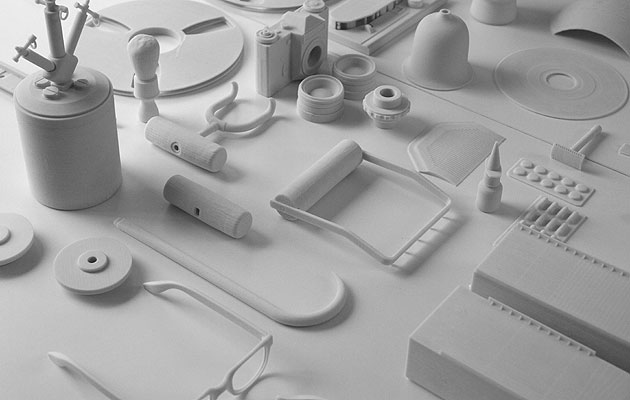

credit Sylvain Deleu Their latest project for the V&A, entitled I Cling to Virtue (the motto of the Kennedy family), develops this narrative approach, retaining a similarly vague space of interpretation between the object and its audience, a charged void in which the cinematic imagination can be nurtured. Only this time, their medium is the family saga. Toran comes from Eastern European Jewish stock and was born and raised in New Mexico, while Kular comes from a Sikh background in Huddersfield. Sharing their family stories with one another, Toran and Kular have developed a strange hybrid of their respective roots, mixed in with elements of famous families and key 20th-century moments. The result is the fictional Lövy family history, narrated by the present-day Monarch Lövy. Once again objects – this time displayed in antique glass vitrines – are used to convey moments from different stages of the saga, providing a curious dreamlike addition to the museum’s rambling collection. “We are trying to complicate the idea of an archive, by making the basis of that archive someone’s memory,” says Toran, recognising that memory is a flexible and flawed thing, and that family history can be as slippery as the bar of soap depicted in one of the displays. “We are interested in the boundary where myth and memory start to merge.” Embedded in the Victorian institution’s sprawling archive of 4.5 million objects spanning 5,000 years, they couldn’t have a more appropriate setting. In each case, the stories are represented through the narrator’s personal impression of the event in question. A tale told to him when he was a child might be represented in childlike form, such as the Lego model of an Indian farm. Others are more sinister, like the force-feeding tube which lies alongside a toffee hammer, relating to a daughter’s rebellion against her suffragette mother. Stories range from the exceptional to the banal as the Lövys are thrust into the 20th century, as well as experiencing the day-to-day mundane, generic family truths drawn out through personal accounts. Sublime and ridiculous collide in this surreal curiosity shop, a sardonic wit pervading each tale. Does this relfect an unusualness in Toran and Kular’s own family histories? ”There is absolutely nothing amazing or out of the ordinary about our families’ stories,” says Toran. “I think all families are very colourful.” What unites these wayward heirlooms is their eerie material finish: produced on a rapid prototyping machine, the objects have the mute, generic quality of untreated porcelain, like ghostly apparitions carved from the narrator’s memory. Lying inert, as dormant props, they can be decidedly unsettling, and this blank ambiguity is crucial. “Every object is a ‘screen’ onto which we project use, affection, anger, desire, freedom,” says Toran. “For us, what adheres to an object is much more important than what it ‘is’.” In their anonymous whiteness, these strange souvenirs create a fertile gulf for our own projections. The rapid prototyping process has become a hallmark of Toran and Kular’s work – the resin objects of the MacGuffin Library were printed “live” in the first exhibition, conjured from the machine’s soupy black abyss – and there is something perversely compelling about subverting a process used for industrial production to make dreamlike totems that are solely meant to be reflected upon. In their blank state the objects take on a beguiling quality, alchemical fragments that might channel a family member from the annals of history, and the sterile, mechanised production adds to this alien quality. “We are interested in working with this new language that is, to some degree, indefinable,” says Kular. “These objects sit somewhere between the product, the sculpture and the prop, so it is appropriate that their material could summon other mediums.” Just like their objects, this cerebral duo refuse to be pinned down, happily crossing between the worlds of design, conceptual art and filmmaking with agility, unfazed by disciplinary classification. “I don’t think we need to define ourselves,” says Toran. “We are very fortunate that, more and more, our work is being accepted in different mediums and is being criticised through the discourse of those different mediums.” Dodging their own penchant for taxonomy, Toran and Kular have carved out a beautifully peculiar place, a world of carefully choreographed absence in which the literary and cinematic imagination is free to run riot. |

Image David Levene

Words Oliver Wainwright |

|

|

||

|

credit Tim Miller |

||