Stockholm’s rising designer, Simon Skinner, builds on his Afro-Caribbean heritage to tell a broader story of Swedishness

Words by Francesca Perry

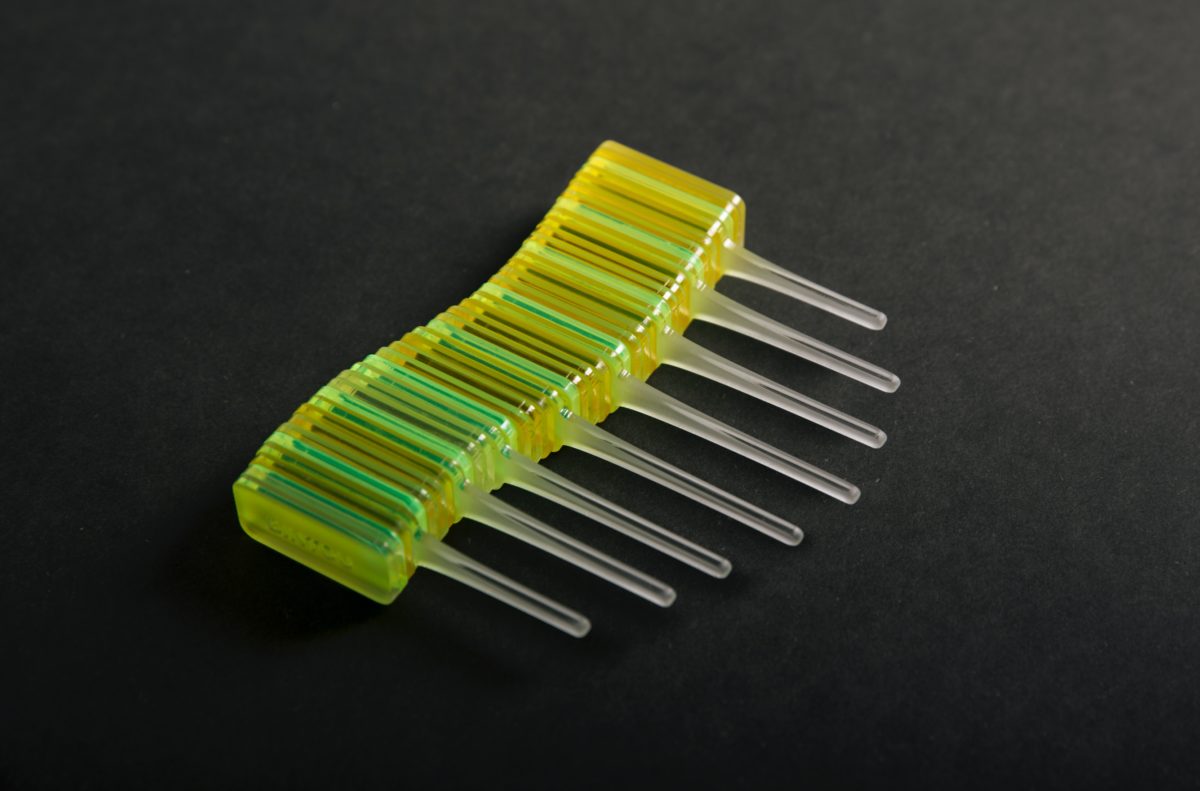

30-year-old Swedish designer Simon Skinner is challenging what Swedish design means, and who it represents. The Stockholm-based creative is trained in industrial design – with projects ranging from lighting and benches to sculptural explorations – and has risen to prominence internationally with his Afropicks project, a range of afro combs in bold graphic forms, for which the designer was shortlisted in the 2020 Wallpaper* Design Awards.

The collection of eight unique picks – launched in 2019 and produced using laser-cutting, casting and 3D printing – celebrates the plurality and diversity of Black and mixed-race identity in Sweden. As part of the project, Skinner interviewed eight different people with African heritage about their lives and perspectives on what it means to be Swedish; each comb is named after and inspired by an interviewee.

Skinner’s own Afro-Caribbean heritage served as a point of reference in his 2020 design for a cabinet, which is decorated with flame-like embellishments celebrating patterns seen in the annual Trinidad and Tobago Carnival.

Much like the Afropicks range, the cabinet – which blends wood and acrylic offcuts in a form that seemingly defies gravity – is both a stylish utilitarian product and a narrative-infused creation investigating, in Skinner’s words, ‘mixedness’. I spoke to the designer in November about his route into design, his work’s ambitions and what’s next.

When and how did you realise you wanted to be a designer?

I didn’t realise that a career as a designer was possible when I grew up, and didn’t have any immediate role models or inspirations that had taken that path. But I’ve always been curious about the way different objectives and environments coexist. I think a lot of my early explorations can be attributed to my restlessness.

Before art school, my creative outlet was through graffiti and just weird stuff that I built at home. I wasn’t very attentive in high school and at one point started to draw endless variations of lamps on a piece of paper. Ideas started coming from nowhere and it was sensational to transform materials and shapes into tangible constructions.

It was my best friend’s uncle who told me that a career doing just that was in fact possible, and guided me to Konstfack – University of Arts, Crafts and Design [in Stockholm] – which is where I was given the foundations that solidified my curiosities.

What would you say are the aims or objectives behind your work?

If the visual language is a force with the power to reconstruct perceptions of reality, then that is the objective behind my work. Having grown up in a multicultural environment, I developed a heightened awareness which directly contributed to my curiosity towards different class systems and their effect on people. How are these systems structured?

Is it possible to transcend them – and what could that look like? Those are questions that influence my process today. With that in mind, I use design to investigate social codes and symbols in society with the objective to deconstruct and reconstruct the meaning they carry.

The Afropicks project started with an interrogation of ‘Swedishness’. How does your work seek to counter assumptions about Swedish design?

Afropicks allowed me to give multicultural perspectives an outlet through an object that carries deep historical roots and heritage. The object, an afro comb, has a standard design which historically has been a symbol for Black pride and power. I wanted to create a collection that encapsulated the comb’s symbolism whilst also channelling stories of in-betweenness and fluidity.

In the eight-piece collection I explore shapes, materials and colours, which through the process came to symbolise ‘mixedness’, whilst elevating the traditional comb design. Behind each comb is a story and behind each story is a person.

By giving these stories an outlet, it also aspires to challenge narrow perspectives of what Swedishness and Swedish design is. I would say that Swedish design is under development, and inevitably so. It cannot continue to stay stifled – right now it’s not inclusive of how Swedish society actually is. It needs to adapt to the experiences that it’s made up of – just like an afro comb can bear the meaning of the people that use it.

Your cabinet piece pulls in references to your Caribbean heritage. Can you tell us more about it?

Historically the cabinet is a piece of furniture that symbolises high status. Looking at both traditional and modern styles that are applied in exclusive cabinets, I wanted to play with new references and manufacturing techniques. Influenced by Scandinavian design, street culture and the annual Carnival in Trinidad and Tobago, this became a style and material investigation bound to mixedness.

I combined wood with offcuts from acrylic sheets. I realised that the decor was removable, which made it possible for anyone to add their own pattern beneath the frosted acrylic, using only pen and paper.

In the future this approach is going to be conventional, and conventional is often synonymous with class. Imagine someone looking at this cabinet 50 years from now, finding themselves represented in history.

How do you address environmental sustainability in your work?

I approach environmental sustainability with quality and small-scale production. I want to create objects with meaning, which form a connection to their owner that can carry on over time. If you manage to secure that connection, then I believe you can create a more sustainable design and production ecosystem.

So you’re not so interested in mass production?

So far, my furniture objects have been the result of creative experiments, not necessarily made for mass production. I’ve had a playful approach to these designs which is a trait that I try to embed in my work. Doing such projects once in a while helps to keep my curiosity alive.

What’s next for you?

I’m currently working on two very exciting projects. One is the launch of a new collection of afro combs that will be presented within a context that deserves to be celebrated.

The other is a collaboration that aims to understand and shine a light on perspectives in a group that’s almost completely underrepresented in society.

Photography courtesy of Simon Skinner

Get a curated collection of design and architecture news in your inbox by signing up to our ICON Weekly newsletter