words Johanna Agerman

Martin Margiela is looking at me intensely. It’s difficult to tell if he is surprised or just pissed off, but I experience a bittersweet sensation, a feeling of triumph tinged with guilt. I’ve finally found a photograph of the famously elusive designer and it’s obvious that he doesn’t like having his picture taken.

“He looks like Jesus,” a fashion editor once told me. On the other hand, a story in a recent issue of British Vogue suggested that Martin Margiela might be a woman. On some online forums there are theories that he doesn’t exist at all, or if he does he left his eponymous Maison shortly after Diesel founder Renzo Rosso bought a majority stake in the company in 2002. The speculation surrounding the obscure designer makes for one of contemporary fashion’s biggest mysteries.

So who is Martin Margiela? That’s a question people love to ask but few try to answer. In the past six months the chatter has been particularly intense as the label has celebrated its 20th anniversary with a “best of” collection for spring/summer 2009 and a retrospective exhibition at the Mode Museum (MOMU) in Antwerp. Still, even the most basic facts of Margiela’s life are confused. People believe he was born in 1959 (wrong) in the town of Leuven (wrong), and that he started his fashion studies at the Royal Academy of Art in Antwerp and graduated in 1979 (wrong). It’s time to find out the truth.

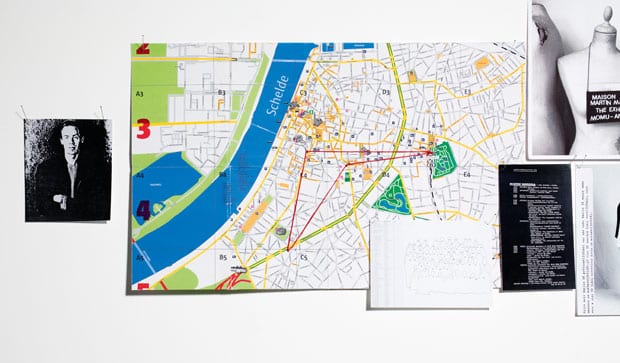

It’s a crisp and clear day when I step off the train at Anwerpen Centraal. The words of Samantha Garrett, the long-serving press manager at Maison Martin Margiela, are repeating in my head: “If it’s Martin’s profile you wish to do, then I’m pretty sure it’s going to be awkward and difficult.” The Maison famously only answers questions by fax or email and never talks about Martin as an individual. Here, in Antwerp, Margiela honed his skills as a designer. It’s a good place to start the search.

The first stop is the retrospective at MOMU. At the opening four months ago, the foyer of the museum was covered in over-sized silver sequins while a brass band played outside. A tiered white birthday cake was presented to the Maison, but Margiela himself was nowhere to be seen. “That is the consequence for him,” says the show’s curator Kaat Debo. “If you decide to be anonymous you have to be it all the way.” Together with art director Bob Verhelst, Debo devised the exhibition. It shows Margiela’s work as rejecting conventional beauty and embracing deconstruction and the incorporation of the old, the already used, a quality not normally associated with fashion at this level. It manages to be conceptual but at the same time practical. This is for example the premise of the Artisanal collections, hand-sewn in the Paris studio, where old items of clothing are torn up and rearranged as new garments. Skin-coloured gloves become a halterneck top, a roll of gauze a tailored jacket. The materials are themselves banal and without value but conjured into garments with the most skilful tailoring they are turned into wearable art. A few days later, when I speak to Margiela’s childhood friend Inge Grognard, the make-up artist for all his shows, she tells me that Margiela was interested in the second-hand as a teenager. “We loved to go to fleamarkets because we had no money to spend on clothes,” says Grognard. “We both liked things that looked like they have had a life before.” Grognard met Martin through his niece when she was 14. Martin was 15. “We had the same interest in fashion and bonded immediately. We always talked about clothes and dressing up.”

Even if Margiela wasn’t there on the opening night, he helped with the installation a few days earlier, Debo tells me. So what is he like? There is a moment of hesitation and the conversation comes to a halt. “It’s difficult, because I respect his wish for anonymity, but my collaboration was a very nice one and very respectful. He is a very calm, relaxed and happy person.” Then silence. It’s curious how people who are not even friends with Margiela clam up at the most simple and straightforward questions about him, making you feel like a scandal-hungry Fleet Street hack just for asking.

The policy of no interviews can be interpreted as a shrewd move in a time when the media makes celebrities of everyone, but the company line is that it was put in place to focus fully on the collection and so that the entire team gets equal credit for the work they produce. The anonymity extends to the way that Margiela covers the models’ faces on the catwalk, often with skin coloured veils; to the all-white interiors of the stores; to the staff that always wear white lab coats to cover their clothes, a nod to haute couture ateliers. Still, not a single season passes without a mention of the fact that Margiela is notoriously elusive. By obliterating himself he has managed to put his incognito persona in the forefront of people’s minds. At the same time it is a refreshing stance in an industry where fashion editors and designers are trained to rub each other’s egos with empty accolades after each show. By not partaking Margiela challenges the industry’s habits, and his success – last year the label had sales worth $80 million – shows that this attitude is lucrative.

“It has sometimes been taken as being pretentious or being a mystery or creating himself as a legend,” says Bob Verhelst who studied and worked with Margiela. “But he has never been busy with that, Martin is not like that. [He thinks] the way I look, that’s none of your business, my work is what I give to you and that you can talk about. You can destroy it, you can like it but my life is my life.” Verhelst is a handsome man around the same age as Margiela. He tells me about the years together with Martin at the Royal Academy of Arts in Antwerp and the six students who later became known as the “Antwerp Six”: Dries Van Noten, Dirk Bikkembergs, Dirk Van Saene, Ann Demeulemeester, Walter Van Beirendonck and Marina Yee. “When we went to Paris the French were laughing and saying, ‘Oh how interesting that you study fashion in Antwerp, we didn’t know that fashion even existed there’. We were treated like idiots. When you are treated like that you react by thinking, ‘just wait and see’.” Verhelst is talkative but when asked a simple question like “what does Margiela look like?” his answer is curt: “Wrong question.” Long silence. “So many times people ask me and I never answer. Also I often say, how do you know it’s a man, it might be a woman.”

That evening I go through a list of Margielas in the Belgian phone directory, hoping that someone can bring some reality to the designer. There are about a dozen of them and I pick a number at random. Someone answers almost immediately. “Yes hello I’m writing a piece on Martin Margiela …” I say. “He’s my brother,” interrupts a gentle, male voice on the other end. “But I don’t speak about him.” It’s an abrupt call, but it confirms that Martin Margiela is real. He’s not a ghost, or a woman.

The files of press releases, exhibition leaflets and press clippings in the Mode Mueum’s library do most of the talking. Here photocopies filed in green folders pull Martin Margiela out of the shadows, telling the story of the man before he turned himself into a “Maison” with the help of business partner Jenny Meirens in 1988. Here he is without 90 staff to do the talking for him. I find out that Margiela was born in the town of Genk in 1957 and took a foundation course at St Lucas School in Hasselt before studying at the Royal Academy of Antwerp between 1977 and 1980. Then he spent a couple of years in Milan, before setting up a small studio on 12 Leopoldstraat back in Antwerp.

When I visit Leopoldstraat I find a white 1930s building, but it’s empty now. It was in this studio that he gave one of his rare interviews, to British magazine Sphere in 1983. Surrounded by books, odd shoes and remnants of fabric, he talks about his first brush with fashion as a child. “I was watching the TV news and there was an item about [fashion designers] Rabanne and Courreges. As soon as I saw their designs I thought, ‘how wonderful, people are doing the sort of thing I want to do’.” In the same article he admits to liking women with big noses and a longing to move to Paris. He left less than a year later to start work with Jean Paul Gaultier.

From 198o to 1988, Martin Margiela did not produce a collection in his own name, apart from entries to two Belgian fashion competitions. “I think he was cleverly preparing himself until he was ready,” says Verhelst, hinting at Margiela’s strategic side. “He didn’t feel like he had to start his own collection immediately after stopping school. Instead everything was well-prepared.” He can still remember the first collection vividly. “It was really a shock for everybody to see Margiela’s first silhouettes, the slim shoulders when everybody was still with padded shoulders, the unfinished garments. At this moment you realised that he was much more advanced than everybody else. He was predicting the years to come.”

In one of the folders I find the black and white photograph – his stern look, his dark clothes, his blondish hair and well-defined lips are captured for me to study in detail. But why does the fashion press seem so reluctant to do the same? “The fashion industry is built on myths,” says Alistair O’Neill, head of the fashion history department at Central Saint Martin’s in London. “The respect that fashion journalists have for Margiela and his personal identity is held in them wanting to believe in and perpetuate the myth and allure of a mysterious creative.” The close relationship and vague boundaries that exist between fashion designers, their investors and the press create an entirely dependent journalistic voice that rarely dares to be more than politely curious. It’s a charade that everyone has a stake in upholding, but also one where Margiela plays into the hands of the system that he has challenged. As frustrating as it is to admit, there is only one person that has the power to reveal the real Martin Margiela, as Kaat Debo concludes. “If there will be a moment in the future when Martin Margiela decides to step out of the shadow, it will be him that decides.”

All images: Andrew Penketh