|

|

||

|

Occupying a bleached-out building on a busy street and marked only by a small logo, the Center for Land Use Interpretation (CLUI) has spent nearly 20 years redefining geography, and inviting the public to join them. This isn’t about mapping roads and elevations, but looking at more unconventional aspects of the land, from satellite dishes scanning the skies to hidden networks of oil extraction in our own neighbourhoods. CLUI cracks geography open to reveal its fascinating links to culture and history, and has made it an urgent, compelling subject attracting entirely new audiences. At CLUI’s library at its Los Angeles headquarters, labels reading Cartography, Oil, Utopias, Water, Incarceration, Shipping, Trash, Mining, Aviation and “Nature”, among others, line the shelves. The library is half organised by topic, and half by each state in the US, sharing the room with a row of black filing cabinets stuffed with maps. A gallery occupies the front of the headquarters and a cat wanders the rooms, dutifully ignoring the activities of the staff. The library’s “Nature” label is quite deliberately written in scare quotes. Matthew Coolidge, who founded CLUI in 1994 in Oakland, California, asserts that we are in the Anthropocene era: there is literally no part of the planet not affected in some way by human activity. This viewpoint underlies CLUI’s scope, which – through exhibitions, publications, an encyclopedic website, and bus tours – examines specific examples of how land has been, or is being, altered by human endeavours. Past exhibits examined subjects like the architecture of law enforcement training centres (Icon 090), exurbs, parking lots, antennas, traffic control and helipads. It is geography by way of cultural studies and history and, as such, CLUI maps, categorises and analyses landscape through a kaleidoscopic lens. Coolidge adds, “There are an infinite number of layers of information that hover above the geospatial template. And CLUI’s layer is infinitely broad.”

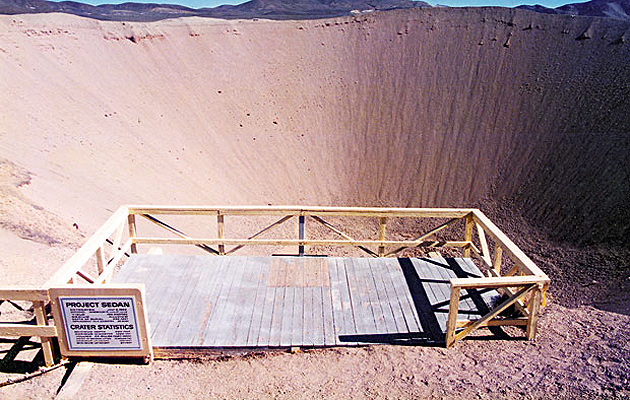

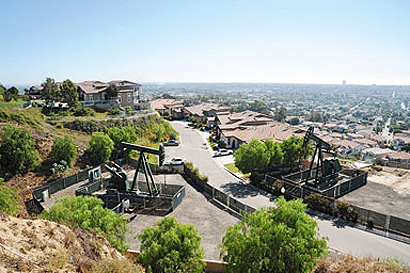

Despite the range of concepts around land use, Coolidge emphasises CLUI’s focus on physical places and artefacts. “Our projects are always anchored in specific examples, and always site-based,” he says. The centre arranges themed bus excursions, which also serve as research trips, with findings being included in later exhibitions and guidebooks. As some introductory wall text in the gallery reads, “There is no substitute for being there, especially in these increasingly virtual times.” In 2009, CLUI organised a bus tour as part of its exhibition “Urban Crude: The Oil Fields of the Los Angeles Basin”. The tour – which sold out seven minutes after it was announced – brought curious locals to the westside of Los Angeles, which is the most urbanised oil field in the country, through the city and down to Long Beach, a coastal area that produces 16 million barrels a year. On the way, they stopped several times to see derricks disguised in scaffolds of painted plywood in the midst of Beverly Hills, oil fields abutting malls, active drill rigs next to suburban homes, and defunct pumpjacks nearly obscured by the encroachment of shops, restaurants and apartment buildings. They also spoke with oil company representatives, a well operator, and a real estate developer. The end of the tour was a visit to THUMS Islands in Long Beach, named for an acronym of the oil companies Texaco, Humble, Unacol, Mobil and Shell. Designed in the late 1960s by a landscape architect who had also worked on Disneyland, the islands are a massive oil extraction complex, camouflaged on the shore-facing side with palm trees, waterfalls and coloured lights. CLUI excels in charting and revealing layers of our landscape that are overlooked or unknown. By pointing out elements of our surroundings that hide in plain sight, their projects encourage viewers to have a keener, more scrutinising eye.

The political aspects of mapping and representing land subtly thread through many of CLUI’s projects and help explain why its work is appealing to a much larger audience than the geography community. To date, CLUI’s work has been shown in numerous museum exhibits including the 2006 Whitney Biennial, the Graduate School of Architecture at Columbia University and the Barbican Art Gallery in London, and covered in a wide range of publications. This autumn, as part of the annual International Symposium on Electronic Art, CLUI will focus on Sandia National Laboratory in New Mexico, a national defence and solar energy company owned by Lockheed Martin. CLUI plans to investigate Sandia’s ground-based remote sensing technology, which scans the sky for foreign satellites. It looks for who is looking at us, and who is potentially scanning and mapping our landscape without our consent or knowledge. It is a subject that is on one hand about the land use of a desert covered by enormous satellite dishes, and on the other, about war games, espionage and the political advantages of controlling cartography. CLUI has come of age in parallel with a revolution in mapping. In 1994, satellite imagery was opened to commercial use, enabling itto function for purposes beyond national defence, and eventually leading to programs like Google Earth. During this period, CLUI had been making its own online maps linked to photographs of the ground. At every step, the technology leapt forward. As if to acknowledge this fact, one of CLUI’s recent expeditions was a visit to the Garmin International headquarters, a company that makes sat navs.

Yet CLUI notably straddles advanced imaging technologies with an interest in idiosyncratic historical methods. With so much information evaporating into the virtual realm, it is rather refreshing to look through the wall of black filing cabinets in its library, which functions as the analogue version of its Land Use database. It is stuffed with a collection of creased paper maps, peculiar brochures and ephemera, and crowned with a row of eccentric field research souvenirs – like a vial of salt from Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats, a bottle of beer with a Spiral Jetty label and other things you can’t (yet) summon on your iPhone. Today, CLUI’s online Land Use database uses Google Earth and presents an interactive national map with markers in each state. You can search by location or subject to discover one of the dozens of sites CLUI has identified as points of interest. There’s Almost Heaven II, a community of right-wing Christians in rural Idaho who have moved near each other to live off the grid; a ghost town in Alabama; Barking Sands Missile Range Site in Hawaii; and Maine’s Pratt Farm, where a lone art historian built earthwork sculptures based on ancient mounds and labyrinths. Notably, these are not sites that would be likely to show up in a tour book or historical guide. They provide an alternative map of the country, devoid of the hotels and businesses that appear on Google Maps. (Listings on Google are offered as a free service, but Google encourages clients to sign up for its fee-based advertising programme to enhance the listing on the map.) Intentions are a key aspect of mapping and gathering data about land and land use; those who control the information about a landscape, control the landscape itself. Therefore, CLUI’s photographs of its projects are an important facet of its work, attempting to offer a straightforward documentary look at a site and its context. Coolidge defines CLUI’s approach to documentation as “ground truthing”, a term commonly applied by cartographers to verify aerial and satellite imagery. He says, “We want to keep our images filtered through one independent agency to make sure they’re apolitical and not commercial. That’s why CLUI representatives take all of our documentation. We never source from stock photography or online image searches.” The aim is for the photograph to be good but not overly aestheticised, and to portray the site as accurately as possible. Ironically, a specific aesthetic does emerge: that of the influential New Topographic school of the 1970s, for which artists like Lewis Baltz and Robert Adams made unflinchingly factual landscape photographs devoid of subjective opinion or romantic idealism.

When I visited the centre this spring, the exhibit Initial Points: Anchors of America’s Grid was on view, which looks at the remains of the first federal survey, launched in 1785 in order to organise the “empty” lands of the west and south into consistently-sized squares. By 1881, 32 Initial Points (the intersection of a baseline and meridian) had been marked, tethering a conceptual grid to the ground. As the accompanying text read, “All [Initial Points] are ground truths, anchored in history at the points between the idea of the nation and the nation itself.” In the middle of the room, surveying equipment is displayed; from a notebook using the boustrophedonic system that measured distance by the amount of land a person and an ox could work in one day, to today’s electronic theodolite that combines GPS and infrared sight. The exhibit documented CLUI’s visits to these 32 Initial Points to see what has survived. Photographs show that a few sites remain, marked with stone monuments. Others have been paved underneath a highway or exist only as small metal discs embedded in the ground. Nearly invisible today, these points were once instrumental in expanding the nation’s reach and claim to ownership. Surveying tools and tiny discs might sound like the makings of a very niche-audience exhibition, but at its core it shares, like all of CLUI’s projects, a quiet call to action. Land use has an undeniable political dimension, but CLUI’s tone and documentation is consistently neutral, leaving viewers and participants to draw their own conclusions. They acknowledge that land use is a fact, not something to be judged or validated. But their projects still encourage us to explore the familiar and overlooked, to verify abstractions with first-hand experience, and to discern the infinite layers of information hovering over our landscape. They encourage us to look closer, to really be there.

|

Image Centre for Land Use Interpretation

Words Lyra Kilston |

|

|

||