|

|

||

|

A decade ago Herzog & de Meuron started turning an old brick power station on the Thames into an art museum. The Swiss architects have just done the same thing in Madrid, but the Caixa Forum couldn’t be more different from Tate Modern. Giles Gilbert Scott’s Bankside power station had everything a museum could want: a dramatic location, an iconic form and a sense of space to fill you with awe. Jesus Carrasco-Muñoz’s power station, built in 1900, had none of those advantages. Consequently, Herzog & de Meuron have had to work a lot harder here, and the result is brilliant but flawed. The Paseo del Prado, Madrid’s showpiece boulevard, tree-lined and traffic-choked, runs through the densest concentration of art in Europe. Connecting the Prado – one of the world’s great museums – the Thyssen-Bornemisza and the Reina Sofia, all of which have undergone ambitious expansions in the last couple of years, it’s a parade that only Fifth Avenue’s Museum Mile can equal. The Caixa Forum sits just off this axis. An art and music centre funded by one of Spain’s biggest banks, it is much smaller than any of the surrounding institutions and is the only one dedicated to contemporary art. The boutique to their megastores, it literally turns heads in a way that they don’t.

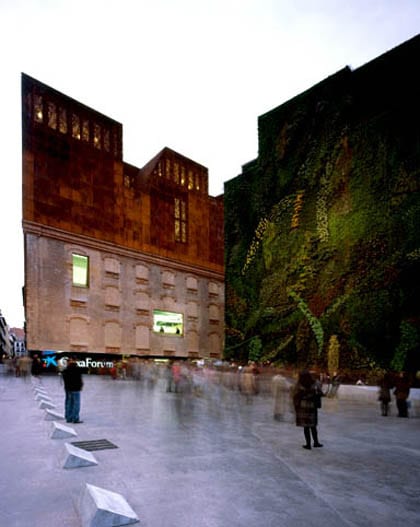

And that’s because you don’t see it coming. Jammed into a tight streetscape, it is connected to the Paseo del Prado only by a small plaza. As you’re walking down the boulevard, the Caixa springs on you like an urban jack-in-the-box. At first it’s the textures that demand your attention: walls of brick and rusted iron set next to a vertical garden designed by French botanist Patrick Blanc. Then it’s the fact that the building appears to be hovering above the ground. This is urban theatrics – the architecture of David Copperfield. There is a real tension in this building between the seductiveness of the brick and iron and the ruthless removal of the ground floor. The original building had a surprising amount of charm for a coal-burning power station. It’s like a backstreet Venetian church from which the marble facade has been plundered. In the afternoon winter light, the bricks are an edible pink. Herzog & de Meuron has filled in the windows, which helps to abstract the host building into a monolithic form, but the gesture is not as significant as it sounds. They were already filled in, albeit not as beautifully. Furthermore, all those sills and architraves suggest floors and rooms that were never there, because this was what Robert Venturi might have called “a decorated shed”. Great iron wheels used to turn in that hollow shell. As if in homage to the Industrial Age technology once housed here, the architects have extended the building upwards in cast iron. Not the treated, stable corten steel so common these days but the old stuff with the powdery rust – the dust-and-bull’s-blood rust that they love up around Bilbao. Harry Gugger, Herzog & de Meuron’s man in Madrid, says they chose the material as a tactile and lively complement to the bricks. It’s what you might call a “real” material, so real that it bleeds after a rain. What a relief to escape the ubiquitous glass-and-steel transparency that is the standard approach to converting old buildings, a tactic that makes architects feel like they’re shining the light of reason on their predecessors’ work. This new iron cap celebrates its opacity. There are no windows as such. Instead, the iron disintegrates in places into perforated screens so that you can look out over the city from the top-floor cafe.

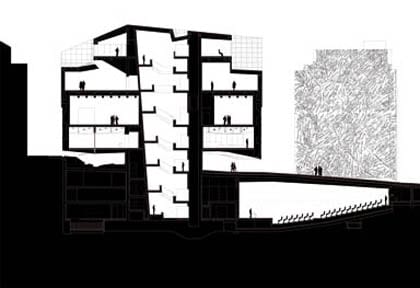

The roof takes what looks like a building and turns it into an object. Gugger says it could have just been a box, but that it was broken down to match the volumes of the surrounding roofscape. It has a faintly mineral shape that only Herzog & de Meuron, specialists in elemental architecture, would have come up with. It also looks anvil heavy, which is paradoxical given that the building appears to be resting on air. First of all, how is it still standing and, secondly, what happened to the ground floor? The decision to cut it away was based on the fact that the building was hemmed in by apartment blocks on three sides and by a petrol station on the Paseo del Prado. “To become a public building we needed to create public space,” says Gugger. Herzog & de Meuron apparently only took this commission on the condition that the Caixa bank would buy the petrol station so that it could make way for a small plaza – room to breathe – and provide an approach from the main avenue. But the architects didn’t feel that was enough. So they supported the building on three concrete cores and removed the power station’s granite base to create a covered open space. Instead of people milling around around the building, they can mill around beneath it. Now that the side of the building has become the front, this overhang serves to “suck in” the visitors, as Gugger puts it.

It was a bold and impressively unsentimental tactic. But the building doesn’t look altogether comfortable. The truncated porticos where the entrance used to be only add to the impression that it has been chopped off at the knees – and there is undoubtedly a loss of dignity in that. Herzog & de Meuron has sacrificed decorum for the spectacle of this amputation. The pay-off is meant to be in the diverting surface of the metal soffit. Its triangulated skin covers the diagonal truss system that’s helping to hold it up. The technique is almost identical to the one under Herzog & de Meuron’s Forum in Barcelona, but – as at that building, which is probably the practice’s weakest – there’s not much sense of what you might do under here. The covered space is dark, and so is a good place to hide from the summer sun, but – unlike, say, the plaza outside the Pompidou Centre – there is nothing to see. There is nothing inviting you to behave a certain way. So what’s it doing here? This question is slightly complicated by the fact that the Caixa has more public space around it than it was supposed to. Well into the construction process, the annexe housing the electrical transformers burned down and made way for another small plaza to the south. This is a boon in the sense that there is now something of an approach from that direction as opposed to the sudden apparition at the end of an alley. However, this does make the strategy of hacking into the building feel rather excessive and gestural. “In the end, we were given too much public space to be true to our concept,” says Gugger. If the covered plaza felt more purposeful, or even more leisurely, then this wouldn’t matter.

The building proper starts on the first floor, and you are whisked up there by a rather lovely faceted metal staircase that brings inside something of the soffit outside. Here there’s a bookshop and ticket desk, and a large window looking out across the Paseo del Prado to the Botanical Gardens. This view makes explicit the existence of that “vertical garden” on the side of the neighbouring building. Plastered with 250 different species of plant, it is meant to create a visual link to the gardens across the boulevard – a strategy that fits into Alvaro Siza’s masterplan for the Paseo del Prado, which aims to reduce the traffic and make it easier for pedestrians to amble from one side to the other. The planted wall has passing madrileños reaching for their cameras but it feels rather like a gimmick. Perhaps when it matures it will lend something more substantial to this setting. There’s a lot more in this building than you would credit from the outside. There are two floors underground, holding conference rooms and a large auditorium for concerts. The auditorium is clad in panels of metal mesh pressed into a pattern reflecting the rusting of the roof – a technique Herzog & de Meuron developed in the dramatic auditorium of the Walker Art Centre in Minneapolis. The galleries on the second and third floors are, well, galleries – big paintings in one (Schnabels, Kiefers and Polkes) and big photographs in the other (Gurskys, Shermans and Wearings), all very mainstream.

All of these floors, along with the cafe above them, are connected by a ceremonial concrete stairwell. This spiral stairwell – a surprise in this context, partly because of its 1920s elegance – completes the sensual richness of this building, which veers from thin bricks to rusting iron to faceted steel and somewhat gaudy garden. There’s a lot going on, and it is all contributing to a sense that one is being seduced by effects. It’s dazzling but it’s not clear what’s tying these textures together. With some nostalgia for its early prismic buildings, I suggest to Gugger that Herzog & de Meuron is less puritanical than it used to be, its buildings less distilled. He disagrees, countering that the early buildings were always “playful”. And to be fair, the Caixa came with a particularly tricky set of conditions, and few architects would have handled them as ingeniously as this. Herzog & de Meuron has always had a particular talent for being unique without resorting to a style. However, this building is a fascinating case study in how an architect deals with a problematic situation; a situation that has been resolved with a little more style than rigour. Click here to comment on this article

|

Image Iñigo Bujedo Aguirre

Words Justin Mcguirk |

|

|

||

Caixa Forum, Madrid, by Herzog & De Meuron

Caixa Forum, Madrid, by Herzog & De Meuron The covered plaza under the museum

The covered plaza under the museum View from the Paseo del Prado, with Patrick Blanc’s green wall

View from the Paseo del Prado, with Patrick Blanc’s green wall The building is tightly surrounded by apartment blocks

The building is tightly surrounded by apartment blocks A small plaza creates a more open approach to the museum from the south

A small plaza creates a more open approach to the museum from the south On the underground auditorium level, the walls have a pressed mesh pattern

On the underground auditorium level, the walls have a pressed mesh pattern The entrance stairway

The entrance stairway The main entrance with steel-covered soffit

The main entrance with steel-covered soffit The concrete stairwell running through the building on the south side

The concrete stairwell running through the building on the south side Cross-section from east to west

Cross-section from east to west